Kung Fu Fighting with the Owl in the Rafters

Welcome back! I hope you’re ready to digest another list of recommended titles, as I’ve been encouraged to break away from the basic themes of my job description and look away from anime and manga whenever I feel appropriate. So, I’ve chosen to take this week to elaborate on a personal favorite genre of film, one that has always dwelt in relative obscurity: martial arts films.(often colloquially referred to as just “kung-fu” films)

To start, there is a certain entry barrier for Western audiences that keeps most martial arts films from being immediately accessible. Like a film about any other performance art like dance or theater, or any other sport like football or baseball, you should understand certain basics of the art or the sport if you expect to really appreciate the genre. The first gap that I find needs to be bridged here is that in Western cultures there really isn’t anything that combines philosophical ideas with physical discipline in the way traditional martial arts have for the Chinese. This leads to the misconception that Chinese martial arts in particular, with their often flowery and dance-like motions, aren’t practical fighting methods on the assumption that all aspects of the art are geared toward combat when that is not really the case. This misunderstanding is hundreds of years old, and the view of marital arts as strange or even laughable is something deeply engrained in many areas.

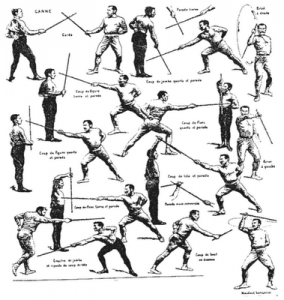

During the age of exploration and colonization in Europe, London became a melting pot of Western and Eastern cultures. Among many other Eastern ideas, the practical essentials of various hand-to-hand, stick fighting, and even adapted sword techniques from Japanese karate, Jujitsu, Judo, and of course Chinese styles of Wushu -the term kung fu or gung fu is infact a misnomer and does not refer to martial arts but to the practice of ______, making “wushu kung fu”, “the practice of martial arts”-, were brought to Europe in diluted forms as part of a popular rising trend of self-defense at the time that utilized bare hands as well as umbrellas and walking sticks as viable self defense weapons against muggers. For practical purposes what was taught in London were purely technique and did little to promote or even explain the mentality behind the exotic martial arts of the orient.

Traditionally, Chinese wushu is more than simply a system of self defense; it promotes physical fitness, mental stability and self-control, as well as spiritual well being and peace with oneself above all, the martial aspect being an extension of physical wellness. The essence of wushu has never been to build hulking muscle mass, but to press the limits of what any body can manage for the sake of longevity and all around good health. Some styles even going as far as to incorporate traditional Chinese medical practice like acupressure, acupuncture, and bone-setting directly into training.

The marriage of martial arts and self defense was something born out of necessity throughout China’s long feudal history where it ingrained itself into aspects of China’s folk lore and historical mythos in a way unlike anything in Western cultures. The closest example I can think of would be the knights of Arthurian legend or the warriors of Greek and Roman empires, but those hold a higher social status in their cultures where as reverence for martial artists was more akin to the respect one gives an artist than that of a soldier or sportsman. Soldiers and knights, like Japan’s Samurai were a class and profession in their societies, but the reach of wushu in China was not bound by social class and martial arts schools would accept and teach students from all walks of life.

With what little of the rich cultural history of martial arts that the Western world ever had adopted receding from Western shores in recent years, what has been left of the modern appeal of martial arts overseas boils down to a mix of gritty action film appeal that caught on in American film during the 80s and 90s -exemplified in Western produced action films like Jet Li’s Danny the Dog (aka Unleashed) and The One; the artistically beautiful direction and choreography of internationally acclaimed films like those of directors Ang Lee or Yimou Zhang of Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon and House of Flying Daggers fame, respectively; and the nostalgic, sometimes mystical, and often comical image of wushu still lingering from the peak of the kung-fu film industry in the 70s and 80s like Korean film Volcano High or American director Rob Minkoff’s Forbidden Kingdom. In any case, the long standing history and tradition behind the practice is most often the furthest thing from the minds of Western audiences.

I could easily recommend, praise, and review any number of award winning films with international reputations like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon or must see classics like Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon, but instead of trying to educate on the artistic merit of martial arts films, I’d like to recommend you some films that will more readily keep you entertained from start to finish, and that will not build an immediate artistic appreciation as much as they will wet your pallet and, with any luck, build you an appetite for martial arts films that you can begin looking to feed yourself.

Starting with what I think is the most easily accessible and what I think holds the most general appeal, yet oddly enough is the title that draws most on elements of nostalgia, is Kung Fu Hustle, by director and star actor, Stephen Chow. Stephen Chow is known for his long line of comedy films parodying various cliches in modern media and for utilizing wushu in some of the least likely of settings. Among other films he has produced and starred in (Shaolin Soccer, Forbidden-City Cop, and God of Cookery, to name a few) Kung Fu Hustle is the most straight forward in theme, as it directly parodies the golden age of kung-fu films.

Taking place in the mobster ruled streets of 1940s Shanghai, China, the story starts when a buddy duo of street urchins are caught in a failed scheme to extort the name of the powerful Axe Gang. Soon the full force of the fearsome criminal organization comes down on the tiny slum of Pig Sty Alley in search of blood. But what they find are a number of master martial artists hidden in the midst of the impoverished common folk who are willing to stand against the corrupt gang. When the mobsters can’t handle the martial artists themselves, they turn to other marital arts masters working as assassins to finish the job for them, leading to a series of fun, fast-paced, and comical fight scenes.

With an opening that plays upon a very violent kind of dark humor the film quickly changes gears to a distinctly western, cartoony kind of slapstick comedy that off sets the grimmer, crueler violence with goofier, comical violence. Most notable is the dance routine during the opening credits that paints the villains in a wonderful deviously demented, yet comical light. While the film and story both highlight the action and the martial arts, and while the story is still very much heroic -it even includes an obligatory romantic subplot- Steven Chow’s tongue in cheek sense of humor is ever present and will keep you constantly entertained.

The action plays heavily upon use of cgi but also “wire-fu” stunt techniques to bolster the fantasy-like heroic image of the humble martial artists, armed with their everyday tools of trade, fending off the corrupt grip of power hungry, gun wielding mobsters, and of a boy with great potential chosen by destiny to confront the forces of evil.

The film treats the martial artists as myth-like heroic figures even within the confines of the setting, referencing techniques, styles, schools, and mythos that lend to the depth of the scale of power in the world of the film.  What begins with actual wushu styles; the Twelve Kicks of the Shaolin Tam School, the Bagua Staff of the Wudang school, and the Iron Fist and Iron Ring styles of Hung Gar is quickly taken out of the hands of realism as later characters sport a wildly exaggerated and slightly comical portrayal of Tai Chi Chuan, and entirely fictional techniques like, the Lion’s Roar -which originated in the classic Chinese novel The Heaven Sword & Dragon Saber– and a The Seven Strings Invisible Sword, a method of attack via sound played on a guqin -an instrument most similar to the western Harp.

What begins with actual wushu styles; the Twelve Kicks of the Shaolin Tam School, the Bagua Staff of the Wudang school, and the Iron Fist and Iron Ring styles of Hung Gar is quickly taken out of the hands of realism as later characters sport a wildly exaggerated and slightly comical portrayal of Tai Chi Chuan, and entirely fictional techniques like, the Lion’s Roar -which originated in the classic Chinese novel The Heaven Sword & Dragon Saber– and a The Seven Strings Invisible Sword, a method of attack via sound played on a guqin -an instrument most similar to the western Harp.

Ultimately, once well beyond the limitations of believability, we find the final duel is between a man emulating the physical aspects of a Toad via the aptly named “Toad Skill” -again taken from Chinese literature, this time the novel The Legend of the Condor Heroes– and the ridiculous Buddha’s Palm technique taken from the notoriously corny 1982 Shaw Brothers kung fu film of the same name.

Along with a traditional Chinese orchestra providing score, the entire feel of the film is a neat little mixture of the “so-bad-it’s-good” appeal of classic kung fu films today and the nostalgic wonder and awe that genuinely wow’d kids in both China and America during the 70s and 80s.

Moving along to something with a more basic mechanical appeal, I’d like to touch on a film that, in great contrast to Kung Fu Hustle uses practically no cgi, no wire stunts, and is much more serious than comical. Ong-Bak: The Thai Warrior is the international break thru film of Thai martial arts action star, Tony Jaa. You will notice that he is not Chinese and indeed not a practitioner of wushu, but of Muay Thai, the kickboxing style native to Thailand. (also the country’s national sport)

Although Muay Thai does not share wushu’s intrinsic ties to philosophy it is deeply ingrained in Thailand’s history as is its religion and could be seen as a kind of bridge between the physical disciplines of Asian martial arts and the athletic lifestyle of Western boxers. For a variety of reasons -not the least of which is its reputation as a particularly brutal fighting style- Muay Thai has been a heavy influence on many modern MMA (Mixed Martial Arts) sport fighters.

Often a popular style in works of fiction like fighting games, anime/manga, and films as an easily identifiable ethnic theme, Muay Thai is rarely explained to its audience. Muay Thai is sometimes referred to as the art or science of “Eight Limbs”, where as something like Western boxing would be considered a “two limb” style in comparison. Muay Thai’s basic principles employ the regular use of both elbows and knees in addition to punches and kicks.

What makes a punch such an available bodily weapon is the shallow skin and narrow focal point that allows the knuckle on skin contact to deliver sheer blunt trauma to the skin that can bruise, break, and draw blood. Consider for a moment then that the elbows and knees are essentially giant knuckles, natural bone blades built into the body, and that Muay Thai specializes in attacking with both elbows and knees in addition to both punches and kicks. There in lies the appeal of Muay Thai.

Getting back to the film however, Tony Jaa follows in the footsteps of other great martial arts stars and not only takes center screen as a lean, mean fighting machine, but also goes out of the way to show off his peak physical condition with a number of genuinely impressive stunts, again all without the aid of glamorizing special effects.

The story to the film is also true to form of many great kung fu classics, as it follows cliches of having the hero break a vow of nonviolence for the sake of helping others, upholding a strict code of honor, and fighting a host of memorable and genuinely detestable villains. Tony Jaa’s character, Ting, is a young Buddhist priest in a small, poor village who is thrust into a seedy westernized city full of criminals, upholding the waning Thai traditions and morals over the faceless rat-race of industry taking over the urban scene.

Through some convoluted twists a black market goon steals the stone head of the village Buddha and so Ting must get it back. The quest takes him through a fight club where he fights a multitude of other fighters each with a distinct and often laughable ethnically theme (The Japanese fighter wears what looks like a school uniform and goes by the stage name Gojira); runs him up against a gang of drug dealers and a surprisingly exciting “car chase” in tuktuk taxis; and the end of his quest brings him face to face with the black market crime lord in possession of the Buddha’s head and with the villain’s drug abusing, rival Muay Thai fighter bodyguard. The film puts all its effort into the draw of the fights and the action and, apart from a slightly slow start, doesn’t fail to deliver.

The soundtrack is fun and modern with clear signs of traditional Thai music influencing it, setting a good pace and tone for the story, which stays mostly serious -with occasional comic relief from two supporting characters- and the choreography stays fresh and exciting from fight to fight all the way through to the end.

Finally I’d like to touch on one last film that can counter balance Ong-Bak‘s weak story. Fearless, starring Jet Li, paints a heroic epic from the real life historical figure, Huo Yuanjia. As a historical figure, the real Huo Yuanjia was founder of the Chin Woo Athletic Association, which was the first martial arts organization in China to discourage specific association with any one school or style, as well as a national hero as the Chinese representative in a number of nationally publicized fights with foreign competitors which restored national pride in a time of depression brought about by China’s loss of political power to American, European, and Japanese imperialism.

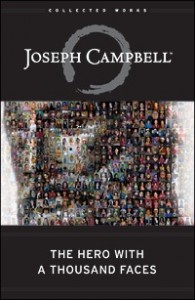

It is with these fights that the movie Fearless starts as Jet Li fights a British bare hand boxer, a Belgian spearman, and a Spanish fencer. Before the fourth and final match against a Japanese fighter, the story turns to a flashback that details Huo Yuanjia’s life since childhood in the format of a classic heroic epic, following the Hero’s Journey as detailed by American mythologist and writer, Joseph Campbell.

For those unfamiliar with the basic theory, Campbell determined that all mythology -everything from Greek, to Roman, to Japanese, to African, to Native American, to Biblical- could be boiled down to a variation on a single plot, which he dubbed the “Monomyth”, or alternatively the “Hero’s Journey”, which he describes in detail in his book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

The basic outline of the Monomyth involves the hero’s call to adventure (often followed by a denial or refusal of the call which must be overcome); a leave of safety into realms (be they spiritual or physical) of the unknown; an acceptance of aide or mentorship from a wiser figure; a series of trials and temptations often revealing weaknesses or shortcoming s that must be overcome; an encounter with elements of death and/or the underworld; transformation and atonement; and finally the return to his roots and the bestowal of his life’s findings to others for their betterment.

This idea and Joseph Campbell himself were chief influences in the global sensation that is George Lucas’s original Star Wars trilogy. Other expanded models of this idea have been made popular by authors like Phil Cousineau and David Adams Leeming in the books The Hero’s Journey and Mythology: The Voyage of the Hero, respectively. This idea has since become a corner stone of creative fiction writing on both a cultural and educational basis and I cannot encourage you enough to read into the subject.

Getting back to the film however, Fearless continues through Huo Yuanjia’s Hero’s Journey, rising to power, falling from grace, attaining truth and redeeming himself, until the film comes full circle to where it began, with Huo Yuanjia ready to duel the Japanese fighter. The story is also rife with historical context as the conflicted regional, style, and school bound pride of China’s martial arts community pits Chinese martial artists against each other while foreign nations assume economic control of China’s major cities over the course of Yuanjia’s lifetime.

The choreography itself is strong and sharp in the way a good fight should be, with some liberal but not terribly heavy use of wire fu. It carries itself with a kind of elegance but never ceases to be about the fighting first and foremost. The fights play on the artistic appeal of martial arts in visual style, but emphasize the science inherent to the practical application as Huo Yuanjia’s fighting style targets key weaknesses and strengths in his opponents’ fight styles.

If a man claims to have perfectly grounded footwork, then attack the center of gravity at the hips; if a man utilizes a clawed open hand that tears with the fingers attack at the joints to seal the move, and so forth. The most basic root of understanding the practical physics of martial arts begins in understanding that all motion begins and ends in different places and that an effective counter measure is to attack between those two points.

If you imagine that the limbs of the human body are each like a whip, you must realize that you cannot stop the whip not by catching it as it cracks, but must intercept the wave of motion before the whip can crack at all. You can’t throw a punch if you can’t move your shoulder, nor a kick if you can’t pivot your hips; you cannot throw a punch without leaning forward, and you cannot move your body forward without first moving the knee, etc…

This idea is inherent in all martial arts, but wushu in particular brings it to the conscious forefront, both in discipline and in film. The understanding of physics and of the human body, the ability to read an opponent and make quick witted decisions, and the physical discipline that ingrains every technique into the body as second nature are what lend martial arts its true sense of mysticism and this film displays those elements brilliantly from start to finish.

I do hope by this point that these films have sparked your interest and that given the chance you will look into one or all of these truly entertaining films, and with any luck develop a taste for martial arts films and will look into this fascinating and little appreciated genre on your own start with what I’ve gone over here as well as some of the titles I’ve name dropped along the way.

If not, I may just write another kung-fu film article at some later date in further regards to the history either in Asia and in the US, reviewing the classic Shaw Brothers films of the 70s, or the world shaking and boundary breaking effects of Bruce Lee on the martial arts world, or perhaps just a few of the many talented martial arts actors I couldn’t fit in today. Until then I hope you’ll wait in anticipation and enjoy my normal articles in the meantime. So, until next time, this has been another fortnight with the Owl in the Rafters.

F*** yeah kung-fu films! You should review Ip Man, because I doubt anyone else here has heard of it and it’s too good to not share. ^ ^

I was thinking if I do more kung-fu reviews they’ll be of actors, and Donny Yen will definitely be one of them.

Kung Fu films be them dubbed or subbed have always been a dirty pleasure of mine and that along with the pleasure of dubbed Dai-kaiju films.

Bargain Gamer and I were actually considering taking a shot at a joint review on a few Godzilla films, starting with Final Wars.

Final Wars… all the cheese and awesomeness. It is perfect match of Daikaiju, Sentai, and japanese etho-centrism to lighten any american’s heart…. and the best thing is that the fake Godzilla gets what was coming to him.