The Owl In The Rafters – Enter The Hero! Bismarck Kamen

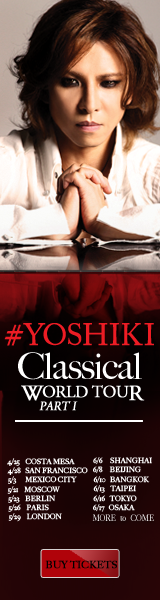

Welcome to another week with the Owl in the Rafters. Normally this is where your host, Tyto, would introduce a name, showcase the artist/author/director’s major works in the Anime/Manga industry, and more or less trick you into reading an abridged biography on the artist, but this week we are going to take a look at things a little differently. This week you are going to get a crash course in the subject of Tokusatsu and its relationship with Anime and Manga, led by none other than the mysterious masked, Owl themed hero, Bismarck Kamen! (That’s me.)

As a fan of both Japanese and Western graphic novels with a heavy slant in the direction of the Japanese, I have very often exchanged questions with American comic book fans about some of the cultural and thematic differences in the two different kinds of graphic novels. In light of the recent slew of Marvel titles like Ironman, Wolverine, and The X Men seeing anime adaptations, one question I got that actually took me by surprise was “Are there any superhero comics in Japan? You know, like the costume wearing, masks and secret identities, Batman/Superman kind?”

At first I thought I was ready with a simple answer, that “Yes, the Tokusatsu genre pretty much covers Japanese superheroes” but I realized before the words could leave my mouth that the answer I had in mind didn’t fit the question quite right.

Tokusatsu is a genre of liveaction film and not a genre or target demographic of Anime or Manga like say sci-fi and fantasy, or shonen and shojo are. So to give a more comprehensive answer to the question, I’d like to take the time to explain a little bit about the quintessential Japanese superhero image and how it appears in anime and manga.

First off, I’ll safely assume that not everyone reading is familiar with what Tokusatsu is,  and so I’ll try to define and relate this genre to you as best I can, starting on the most literal level. The term Tokusatsu translates to something like “Special Picture” and is a portmanteau of the key characters used in the Japanese phrase “Tokushu Satsuei” meaning “Special Photography”, referencing the prominent use of special effects in film.

and so I’ll try to define and relate this genre to you as best I can, starting on the most literal level. The term Tokusatsu translates to something like “Special Picture” and is a portmanteau of the key characters used in the Japanese phrase “Tokushu Satsuei” meaning “Special Photography”, referencing the prominent use of special effects in film.

The children’s superhero shows that featured these special effects often used them to create the illusion of giant monsters, the lightning and fire of special attacks, and the often psychedelic looking transformation sequences that have since became iconic of classic Tokusatsu. Of course, since the dawn of modern technology and the heavy use of CGI in both film and television, the term is no longer used as literally as it once was. Instead, the term now generally covers the live-action television and film genre of the Japanese Superhero. (Technically a few other kinds of shows are considered Tokusatsu, including Kaiju films which are their own genre as well, and puppet shows like Thomas the Tank Engine.)

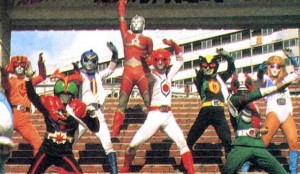

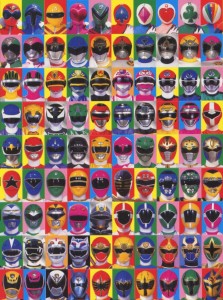

By now most of you have probably been looking at the accompanying pictures and thought of the Power Rangers. Indeed, the resemblance would seem uncanny, but there is good reason for that.

In 1993, when Saban Entertainment first pitched the idea for The Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers to Fox Kids, the pilot episode (and most of the first season itself) was composed chiefly of stock footage from the 16th season of the long running Tokusatsu series, Super Sentai, and in the past 15 years, every new season of Saban’s Power Rangers has been made using the costumes and props of the previous year’s season of Super Sentai in Japan.

(And if you were curious; yes, all of Saban’s liveaction 90s titles like VR Troopers, Big Bad Beetleborgs, and the short-lived Masked Rider were all adaptations of various Japanese Tokusatsu series.)

Now I could go on for pages about just Super Sentai and/or Kamen Rider alone, never mind the whole of the Tokusatsu genre and its history –In fact I did just that, several times even, before paring this article down to a manageable size for the final cut– but for now I’ll suffice with a brief description and relevant notes on the two before moving on.

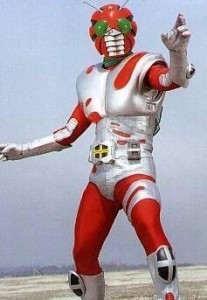

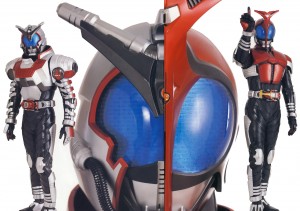

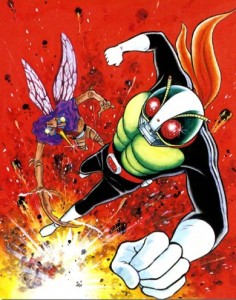

Starting in 1971, Kamen Rider was the first of the two long lasting pillar titles of the Tokusatsu genre to be created by Shoutarou Ishinomori; a man already famous as a manga author and artist at the time and legendary now. I’ll get back to Ishinomori himself later though. As for Ishinomori’s original Kamen Rider, the story followed Takeshi Hongo, a man abducted and experimented on by the evil SHOCKER organization, a lingering remnant of the nazi party dedicated to taking over the world.

The evil SHOCKER organization used Hongo as one of many innocents involved in a super-soldier project. Hongo was operated upon and given cybernetic implants, granting him superhuman strength focused in his legs. His codename: Hopper. Hongo liberated himself from the control of SHOCKER however and turned on his creators in an epic, lone quest to dismantle the evil organization, one monstrous super-soldier at a time.

Perhaps the biggest contribution Kamen Rider had to the Tokusatsu genre and the general superhero image in Japan –Other than the character himself, having since become a near legendary icon– could be laying the foundations of the Henshin-Hero subcategory that makes up the bulk of Tokusatsu, and subsequently the source of that genre’s effects on anime and manga.

For those of you on the up and up with video games, you no doubt recognize the term Henshin, from the tag-line of Clover Studio’s quirky sidescrolling beat’em-up game, Viewtiful Joe, “Henshin-a-go-go, baby!”. Even if you haven’t played the original game, you may still recognize the character, from his appearances in Capcom’s lineup of characters in crossover games like Marvel vs. Capcom 3, and Tatsunoko vs. Capcom.

In any case, “Henshin” (lit. “Change Form”) is the signature transformation call of the Kamen Rider series and has since become the iconic phrase for all transforming super heroes in Japan. The use of a transformation call and the following transformation sequences, while not first used in Kamen Rider, were made popular in great part by Kamen Rider’s popularity and national icon status.

Finally, yet another of Kamen Rider’s little marks left on Japan’s hero image, the legendary Rider Kick (and to some lesser degree the Rider Punch). Kamen Rider’s finishing move has been the inspiration for a great many parodies and throwbacks: If you’ve ever heard a favorite anime character put their name in front of “–KICK!” or even “-PUNCH” as a goofy sort of special attack, then that was probably a reference to one of the original Kamen Rider’s signature finishing moves.

In the years following, the Kamen Rider series has retained a few main themes. First is that the hero’s powers have always come from the same source as the enemy, making for a natural conflict for every new Kamen Rider where they must confront their own moral identity as a potential killing machine or an unwavering force of justice. Second, is of course the transformation command “Henshin!” accompanied by a pose, unique to whatever particular season, and some sort of belt to facilitate the transformation. Third, is the unique variations on the standardized costume which always include a bug-eyed mask/helmet, leather fullbody riding suit, boots, gloves , and windswept scarf. Last but not least is some variation on the signature Rider Kick as a finishing move: in the past 35 years some have been flying kicks, drop kicks, roundhouse kicks, and more.

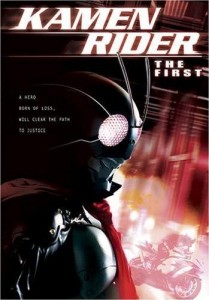

I told myself I wouldn’t do this, but I really can’t help it, so I’m going to do it anyway… I’m just going to drop a few personal favorite titles with perks, as fast as I can, for anyone who might be interested in getting into Kamen Rider for the first time and then I’ll get back to the point, I promise. First must see for any new fan is Kamen Rider The First, a 90 minute movie adaptation of the very first season of Kamen Rider. The movie features some great redesigns of classic characters, a number of very cool fights, and a fun story that’ll keep you interested between fight scenes. Optional follow up is the sequel film, Kamen Rider The Next; an adaptation of Kamen Rider V3 that delivers more of the same cool designs and action as its predecessor while taking a bit of a heavy hit in the story department. Still worth watching at least once and definitely still fun, but i takes a few steps too far over the line into ridiculous territory when it clings to the ongoing pop-idol phantom/haunted music video plot device.

Second is Kamen Rider Dragon Knight, the Emmy Award winning American adaptation of the 12th generation of Kamen Rider, Kamen Rider Ryuki. After the scathing failure that was Saban’s Masked Rider in the 90s, Dragon Knight does a genuinely surprising job of creating a decent original story from scratch. An apt choice on behalf of developer Steve Wang, as Ryuki show cases one of the biggest cast of heroes and villains, with nearly 50 different monsters throughout the series and over a dozen different Kamen Riders, each with multiple forms, unique powers, abilities, and weapons. My recommendation here; watch Dragon Knight, then watch Ryuki. Compare. Contrast. It’ll be a good learning experience.

The season following Ryuki in Japan is one of my personal favorites, Kamen Rider 555. (pronounced like “f-eyes”/”Faiz”/”fives” and written as “phi’s” as in the Greek letter Phi, all for the sake of one big pun.) The story follows two heroes, one of whom is a bit of a goof who stumbles into becoming Kamen Rider Phi’s; the other gets into a car crash, is hospitalized in a coma, and dies 2 years later, only to suddenly reawaken as a monster. The monsters called Orphenochs are the result of an experiment that resurrects the dead. The catch is that the Orphenochs, once revived and granted their powers, owe their lives and service to the Smart Brain company that made them. The story plays heavily on elements of drama and horror film tropes as one of the darker Kamen Rider series. The appeal for me here lies in the monster suit designs which are gorgeously done in a metallic gray monochrome palette that gives off a gothic feel akin to gargoyles and churchgrims.

Finally, I can’t just praise the monster suits and end this without saying anything about the heroes. 2006 marked the 35th anniversary of the Kamen Rider franchise, and to mark the anniversary Kamen Rider Kabuto was given particular attention. The series featured what may be my all time favorite rider costumes. Using a Cast Off system, each Kamen Rider (save two special cases) have a heavy armored Mask form and a sleeker more agile Rider form. The cast off system itself uses a very cool looking transformation sequence where the user first dawns his Mask form through a traditional henshin pose, then jettisons chunks of armor to reveal his Rider form. In addition the Rider form has access to the Clock Up ability, which starts up a really cool kind of bullet time effect.

I know this was supposed to be more about the heroes but the monster costumes in Kabuto are absolutely amazing too. Where as 555s has an almost architectural/sculpture like quality to the monster designs, the monsters in Kabuto are all based on insects and have a wonderfully organic and gruesome quality to them. Between the two, it’s really a wonder more kids in Japan didn’t have nightmares over these shows.

Moving us right along before I really do lose myself to Rider-Mania, I’ll try to make quick work of Super Sentai.  The franchise was originally said to have started in 1979, with the series Battle Fever J, but later adjustments to the official history instead point to the 1975 series, Himitsu Sentai Goranger (Lit. Secret Soldier-Squad FiveRangers) as the first.

The franchise was originally said to have started in 1979, with the series Battle Fever J, but later adjustments to the official history instead point to the 1975 series, Himitsu Sentai Goranger (Lit. Secret Soldier-Squad FiveRangers) as the first.

The story followed a team of five operatives from the international peacekeeping organization, the Earth Guard League (aka EAGLE) stationed in Japan as they combated the secret society of terrorists known as the Black Cross Army. Every episode the Gorangers would combat one of the Black Cross Army’s masked operatives and the Zolder foot soldiers.

It wasn’t until two series later, with Battle Fever J that the element of the giant robot and the inclusion of giant monster fights was added into the mix. This popular trend has since become not only an icon of Japanese children’s entertainment, but thanks in large part to Saban’s work, it has a remarkably similar level of recognition in America as well, although it comes not only from Power Rangers, but shows like Voltron: Defender of the Universe as well.

I know I said I wanted to keep this brief, but I do need to point out that this season marks Super Sentai’s 35th anniversary, and as a special gimmick this year’s addition to the franchise, Kaizoku Sentai Gokaiger (lit. Pirate Soldier-Squad HeroicRangers )  plays upon its swashbuckling pirate theme by having the new rangers “steal” or otherwise borrow the powers, suits, and even mecha of the past 34 generations, even going as far as to reuse all 199 different ranger costumes from past generations as well as calling on previous actors to make cameo appearances as guest stars and even minor supporting roles in the plot. If ever there was a series that could serve as a Super Sentai crash course, this would be the one. You should definitely look into it.

plays upon its swashbuckling pirate theme by having the new rangers “steal” or otherwise borrow the powers, suits, and even mecha of the past 34 generations, even going as far as to reuse all 199 different ranger costumes from past generations as well as calling on previous actors to make cameo appearances as guest stars and even minor supporting roles in the plot. If ever there was a series that could serve as a Super Sentai crash course, this would be the one. You should definitely look into it.

Getting back to the point however, Super Sentai is monumental in that it helped to popularize and in part to establish the long running trend of the archetypal, color-coded, five-hero team that ran rampant throughout Japanese television and in turn American adaptations of those same shows during the 1980s and early 90s: Red is always the strong-hearted leader, Blue is the stoic wingman, Pink is the token girl of the team, and then the last two characters tend to shuffle between Yellow being the big-guy/muscle-head and Green/Black being the nerdy guy. Alternatively Yellow is sometimes made out to be the genki-girl and Green the girly-boy, and other series still have managed to combine the two options into the muscle-headed genki-girl and/or the geeky girly-boy.

Again, I could go on about various different Tokusatsu titles for countless articles without ever getting to any anime/manga, but that’s not the point today. What I’ve been setting the stage for is a line-up of Tokusatsu inspired anime and manga titles that I can share with you. I can’t possibly manage a full breakdown of every Tokusatsu inspired series out there, but I want to try and recommend you some of the ones that require the least amount of background info, that you can really just jump right into and enjoy, and that may serve to pique a bit of interest in you over the live-action genre that inspired them.

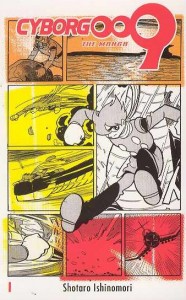

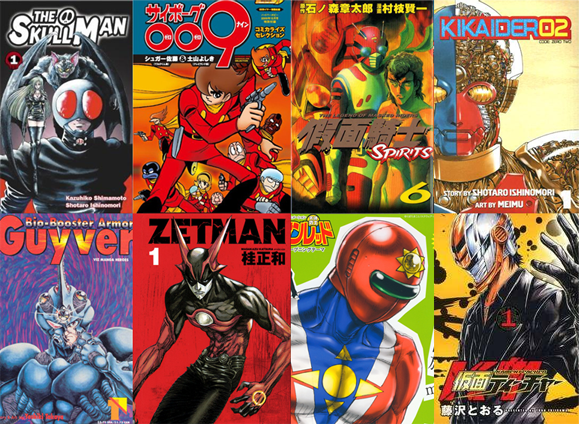

First on the list is of course the work of Shoutarou Ishinomori himself. I mentioned that before (and even after) he became the name behind many of the hit Japanese children’s shows of the 70s and 80s, Ishinomori was a manga artist, and in fact a student of the grandfather of all anime, Osamu Tezuka. The most famous of Ishinomori’s work is a title I’m sure you are all at least somewhat familiar with, the timeless classic, Cyborg 009.

Cyborg 009 actually predates Ishinomori’s Tokusatsu creations, running from 1964 to 1981, but could easily be seen as the basis for his Tokusatsu hits, as it shares a number of traits with both Super Sentai and Kamen Rider. Originally the Cyborg 009 manga saw its first animated adaptations as two films in 1966 and 1967, with the first TV anime airing in 1968, and another running from 1979 to 1980. Some of you may remember that Cartoon Network aired a Cyborg 009 anime on its Toonami block. That was the third anime adaptation of the series that aried in 2001. For the most part all variations on the series do follow the same basic plot, with minor revisions/additions to background stories and other events.

I really could just recommend any/all of them to you if you’re a hardcore anime fan with an appreciation for the classics, but for the sake of younger audiences, and in the interest of casual watchability, I would recommend the more recent television series, the 2001 anime, as the most suitable starting point over the older series or films.

In a world where the Cold War never quite ended, a criminal organization with a strong grip on the black market for weapons of mass destruction has invested cutting edge technology into the development of cyborg super soldiers. The poor innocent souls abducted to be part of these experiments are…

Cyborg 001, a small Russian infant who was given psychic powers; Cyborg 002, an American street thug from New York who was given the gift of flight; Cyborg 003, a young French woman who was given heightened senses of detection;  Cyborg 004 a German man who was thought to have died trying to escape past the Berlin wall and turned into a living weapons arsenal; Cyborg 005, a Native American man who was given super human strength matching that of a dozen men; Cyborg 006, a Chinese chef with the ability to spit fire; Cyborg 007, a British stage actor who was given the ability to shapeshift; Cyborg 008, an African boy taken from the heart of a civil war and given unmatched mobility in water; and finally, Cyborg 009, a Japanese orphan taken and given the Accelerator chip, which allows him to slow down time relative to himself. i.e. He can move at super speeds.

Cyborg 004 a German man who was thought to have died trying to escape past the Berlin wall and turned into a living weapons arsenal; Cyborg 005, a Native American man who was given super human strength matching that of a dozen men; Cyborg 006, a Chinese chef with the ability to spit fire; Cyborg 007, a British stage actor who was given the ability to shapeshift; Cyborg 008, an African boy taken from the heart of a civil war and given unmatched mobility in water; and finally, Cyborg 009, a Japanese orphan taken and given the Accelerator chip, which allows him to slow down time relative to himself. i.e. He can move at super speeds.

Along with their creator, Dr. Isaac Gilmore, the nine cyborg soldiers escape the clutches of the Black Ghost organization. At first the team must learn to trust each other and master their powers in order to combat the pursuing forces of Black Ghost, but they eventually decide that they must use their powers to bring down Black Ghost once and for all.

Of course, Ishinomori also published manga based on some of his hit Tokusatsu series, and other manga based on his work were even published by other artists, including the cult hit manga series, Kamen Rider Spirits. While the Kamen Rider and Super Sentai manga by Ishinomori were both more of sequels or epilogues to the live action series, and the various spinoffs by other authors still expect a sort of pre-established relationship between the reader and the original stories, Ishinomori’s original Skullman manga was a one-shot published in 1970, with a full series later written by Ishinomori fan, Shimamoto Kazuhiko in 1998 and running until 2001, and finally given a short anime adaptation in 2007, all of which act as fairly strong stand alone titles, as well as magnificent supplements to Ishinomori’s other work.

As one of Japan’s premier names in heroism it’s remarkable to think that he also created one of manga’s first real anti-hero characters. The anime adaptation of the 1998 manga series differs from its source material and sets itself up as a potential prequel to Cyborg 009, where as the manga had established itself as a kind of origin story for all of Ishinomori’s major Tokusatsu series, including Kamen Rider, Henshin Ninja Arashi, Himitsu Sentai Goranger, Robot Detective K, Inazuman, Kikaider, and Space Ironmen Kyodain.

The anime follows a reporter named Mikogami Hayato as he investigates rumors of a series of murders tied to a mysterious masked man. What Mikogami uncovers is the violent lone crusade of a man’s bloodthirsty revenge against an evil organization that tore him away from everything he loved and ruined his life. The television series lasted 13 episodes, but also featured a live-action episode 0, entitled Skullman: Prologue of Darkness.

This all brings me to another big name in Tokusatsu related anime/manga, and a personal favorite. Some of you may recall the 13 episode Kikaider anime and the 4 episode OVA that aired on Cartoon Network’s [Adult Swim] block back in 2003. The character Kikaider itself was originally one of Ishinomori’s Tokusatsu characters from his own show that aired in Japan 1972 and actually made its way as far West as to see an American broadcast on Hawaii television. The anime and OVA were based less on Ishinomori’s original television series and more on the manga series by Meimu that ran alongside the original television broadcast, which gave a darker view of the human struggle of the original story.

Playing off of themes borrowed from Osamu Tezuka’s Tetsuwan Atom, aka Astro Boy, and subsequently the story of Pinocchio, the Kikaider anime plays heavily with the idea of knowing right from wrong.

Jiro, the Kikaider unit, possesses what his creator, Dr. Komiyoji, called the Gemini circuit. The Gemini circuit allows Jiro to distinguish moral right from wrong, and with it Dr.Komiyoji had hoped to create a fighting machine capable of fighting for justice against the evil organization DARK (Yes, amazingly corny name, I know) that had forced the good doctor to slave away making weapons of mass destruction. The scheme is found out however and Komiyoji’s lab is attacked. Komiyoji goes missing in the wake of his lab’s destruction, but Kikaider is activated and escapes, albeit with no idea who/what he is or what he is meant to do.

Meeting with Komiyoji’s daughter and son, Jiro learns that he is meant to fight against the forces of the DARK organization. Jiro quickly learns however that without his complete Gemini circuit he is highly susceptible to being given commands by the leader of DARK, Dr.Gill. Battling between what he believes to be right and the commands ordered to him by Dr.Gill, Jiro struggles with his sense of guilt and human emotions. All the while battling the battle ready robots of Dr.Komiyoji’s past projects under the control of DARK.

While the Kikaider 01 OVA received a bizarre drop in art quality from the TV series, it does provide an interesting epilogue, while introducing a number of characters from the original Tokusatsu series that didn’t make it into the first 13 episodes, including Jiro’s brothers, the Kikaider 01 and Kikaider 00 units, named Ichiro and Rei, respectively. Ichiro is a loose cannon, and the original battle design used for Jiro’s construction, but with none of the Gemini circuit’s conscience, while Rei is a defective prototype design and lacks a personality altogether.

For the first three episodes the brothers and sister robot, Bijinder, are introduced along with a young boy, Akira, and his caretaker, Reiko, who are being pursued by agents of an evil organization called SHADOW. (I know, I know, this naming scheme can’t get much worse) SHADOW of course turns out to be the remnants of DARK, regrouping after their defeat at the end of the television series. The final episode of the OVA takes a fantastically dark twist when Jiro’s brothers, Ichiro and Rei, are captured in the final assault on SHADOW’s base of operations and implanted with a Submission Circuit, and forced to fight Jiro, whose conscience won’t allow him to hurt his own brothers.

Jiro is thus captured and implanted with the Submission Circuit as well, but in an unforeseen glitch in programming, the conflicting orders of the Gemini and Submission circuits create the perfect, functionally flawed human conscience that Jiro had lacked. Where as Jiro once only strove to be wholly “good” with a faulty perception of what was right, he now possesses the capacity and will to be “evil” as well with a still broken sense of what is right and wrong. The punch line to this dark joke being that had the Gemini circuit ever really worked properly Jiro would have been less a human and more like a god. The one thing his AI’s morality was missing to make him truly human in the first place was a capacity for evil. I won’t spoil any more of the ending, as it really is a surprisingly powerful end to the story, so for now let’s move on to the next show.

At this point I think something a little more light-hearted is in order, and so now is as good a time as any to address the manga and anime series Astro Fighter Sunred. Taking a hilariously cynical look at how a henshin hero might function in a real world setting, Astro Fighter Sunred is a classic short vignette/skit based kind of gag comedy that bit by bit deconstructs the image of the typical Tokusatsu hero. What we get is a laid back thug of a hero who spends most of his time lounging around his girlfriend’s apartment or gambling away what little money he has at pachinko parlors, because really, what kind of job would you expect a hero to be happy to hold down when he spends his Saturday mornings engaged in fisticuffs with monsters?

Taking place in Kawasaki, a far cry away from the hustle and bustle of Tokyo where most big Tokusatsu shows take place, Sunred doesn’t exactly get a spotlight role in the nation’s heroics market. In a brilliant twist on the super hero image, despite the opening credits showing some classic spandex clad hero on monster beat downs, Sunred doesn’t actually ever wear his hero outfit. Instead he spends all his time in a casual pair of shorts and a tee shirt with sandals, but keeping his helmet on at all times, even while he smokes. (don’t ask how that works.) This of course includes his heroic romps with the local monsters. Speaking of monsters, there can’t really be any call for a hero unless there’s an evil organization to fight.

Enter Florsheim, a nationwide evil organization, fully licensed and certified even! Lead by their confusingly modest and public-spirited section chief, Vamp, the Florshiem monsters find themselves at the abusive mercy of the delinquent hero as they constantly attempt to kill him in his day-to-day life while dealing with their own personal dilemmas. As a large scale organization Florsheim does of course have to deal with financial problems, leaving Kawasaki’s branch with very little funds and a very thrifty and handy leader armed with economical and easy household tips and tricks, including an entire mini-cooking program on cheap simple dishes.

The real beauty of Astro Figher Sunred as a comedy is that it makes obvious logical extrapolations on traditional clichés in Tokusatsu. The hero always wins for example, and when you think about it, if not for the fact that they specifically fight evil, they’re job is to beat people up. Given that they never lose a fight, it also sort of follows that the hero be a bit of a cocky jackass. Put together that confidence and the naturally violent tendencies and you realize the hero is kind of a horrible person. That’s the basis of Sunred’s character. On the flip side, the Florsheim organization’s Kawasaki branch manager, Vamp, is actually a really nice guy (you know, apart from the whole “taking over the world” thing) who shares cooking and house cleaning tips with the middle-aged housewives in the neighborhood where the Florsheim Kawasaki HQ is located. he also has to take good care of his employees and deal with all the same tedious managerial duties an office manager would.

The natural character interaction between quirky stereotypes makes for a genuinely unique mix of super hero related jokes and slice-of-life comedy.

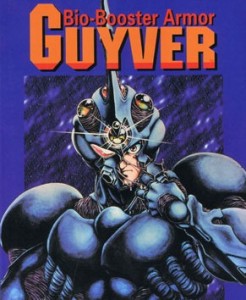

But I’ll assume most of you would be interested in Tokusatsu for the action, and for that there is one name that can’t go without mention. Guyver: The Bio-boosted Armor was a hit manga title by Takaya Yoshiki, published in 1985 and still ongoing. Other than two different anime adaptations the series also inspired two live-action American films by New Line Cinema back in the 90s, directed by two of the suit/prop artists behind Predator. (Don’t let the credentials fool you, though. The suits look great, but the Guyver movies may easily be two of the worst films ever made.)

For all you fan boys however, you’ll probably be excited to know that the second movie, Guyver: Dark Hero, actually starred David Hayter —voice actor of Solid Snake in the Metal Gear Solid series, and screen writer for the first two X-men movies, as well as co-writer of the Watchmen movie— in one of his earliest film roles. To this day he still uses the pseudonym Sean Barker, the name of the main character in said Guyver movie, in place of his own name in certain minor roles.

The Guyver took a gritty spin on the clichés of most solo Henshin heroes. When a young boy, Shou, accidentally stumbles into a bio-weapon and becomes its symbiotic partner, he gets himself, his friends, and his family tangled in a crazy conspiracy involving a major corporation and its development of mutant super soldiers called Zoanoids. The series takes obvious plot cues from its predecessors in the Tokusatsu genre by sticking to the monster-of-the-week format, but the real beauty comes from the drama of Shou trying to adapt to his life as the target of countless mutant monstrosities.

Rather than the glorious hero, we find that Shou is cursed by his powers, unable to live a normal life, and forced to defend not only himself, but his loved ones from danger. In one of the series’ more legendarily cruel moments, Shou’s father is kidnapped by the evil corporation and transformed into a special anti-guyver engineered monster and forced to fight his son to the death. In another instance in the series Shou is actually killed in battle, but the Bio-armor’s self-defense mechanisms require a host and so clone Shou, after which point the cloned Shou goes through a serious identity crisis.

In general the long running series is peppered with great little moments of drama amidst the cascade of violence. I guess I hadn’t actually mentioned it until now, but the characters weren’t the only things to get a dose of the ultra-real treatment. While the live-action medium and the child audience generally limits Tokusatsu to a fairly tame breed of action, Guyver takes full advantage of its flexible medium to spray monster blood and guts all over every page it can.

In a similar veign to Guyver is the manga series, Zetman. Taking the same basic idea of a gritty realworld kind of Tokusatsu hero, Zetman presents us with a young orphan boy named Jin who is a kind of rogue hero in a busy, fast-paced and ruthless Tokyo setting. The boy is of course the result of some bizarre experiment, in this case an artificial human, who was taken from the lab he was born in by his creator, Kanzaki, whom he calls grandpa, and together the two are on the run from the organization that made him and hiding as hobos.

Zetman presents us with a young orphan boy named Jin who is a kind of rogue hero in a busy, fast-paced and ruthless Tokyo setting. The boy is of course the result of some bizarre experiment, in this case an artificial human, who was taken from the lab he was born in by his creator, Kanzaki, whom he calls grandpa, and together the two are on the run from the organization that made him and hiding as hobos.

When the organization behind Jin’s creation finally catches up with Kanzaki they find out too little too late that the site where Kanzaki and the other hobos has been living was torn to pieces and the hobos killed by a freakish monster, and Jin is nowhere to be found. The monsters called “Players” were the result of a series of experiments with artificial life that escaped and have hidden themselves away as human civilians. Since escaping they have formed a kind of law among themselves to stay in human form and not give in to their violent impulses.

Parallel to Jin’s story is that of another hero, a boy named Amagi Kouga, the grandson of the man behind the project that created Jin, and the man whom Kanzaki was running from when he took Jin and hid himself away. Using his grandfather’s funds and resources, Kouga aspires to be the shining white knight kind of super hero he loved as a kid. He dawns a persona like some sort of mismatched Tokusatsu Batman in an Ironman suit and takes off into the night to fight crime.

The two cross paths when the wannabe superhero, Kouga arrives at a burning house to investigate a string of arson cases. As with any super hero story, there are no normal criminals and a fire-breathing Player started all the fires.  Jin is wrapped up in a revenge fight against the Player while Kouga is looking for the culprit and any people trapped in the building when the two run into each other. When the two find a family trapped in the burning building, Kouga tries to evaluate the situation and save the kids before the mother, arguing that they can’t possibly manage to save all of them, so the best thing to do is save the kids. Jin brushes him off and saves both the mother and kids on his own. Jin of course vanishes into the flames to pursue the Player, while Kouga is praised as a hero. The guilt and humiliation of taking credit for something he nearly failed at infuriates Kouga, fueling the start of his rivalry with Jin.

Jin is wrapped up in a revenge fight against the Player while Kouga is looking for the culprit and any people trapped in the building when the two run into each other. When the two find a family trapped in the burning building, Kouga tries to evaluate the situation and save the kids before the mother, arguing that they can’t possibly manage to save all of them, so the best thing to do is save the kids. Jin brushes him off and saves both the mother and kids on his own. Jin of course vanishes into the flames to pursue the Player, while Kouga is praised as a hero. The guilt and humiliation of taking credit for something he nearly failed at infuriates Kouga, fueling the start of his rivalry with Jin.

Another comedy series I want to touch on to help balance out some of the grimmer titles I’ve gone over is Kamen Teacher, a delinquent school set comedy with a healthy dose of action. Written by, Fujisawa Touru, the author of Great Teacher Onizuka (aka GTO) it follows a duo of teacher and teacher’s assistant sent in by a specialty program to help straighten out the students of Kyokuran High, a high school notorious for its violent, delinquent students.

The twist is that the two never appear at the same time, and when the TA does show up around campus, he’s always wearing what looks like a superhero mask. While the goofy teacher, Araki Gouta, seems to be nothing but a bumbling idiot, and a bit of a pervert, who thinks he can get through to his delinquent students through friendship and honest counseling, the masked TA Juumonji Hayato appears to administer tough love to students that don’t listen to reason. Of course, in the current situation, that means Juumonji tends do a little more of the work than Araki.

As the punks of Kyokuran’s class C, when the dynamic teaching duo show up and start meddling with their carefree do-nothing lifestyle, they start calling on the toughest guys they can find to take the mysterious TA down a peg. Problem being that rumors of delinquents being beaten up by their teachers also ruins their reputations and so other classes, and eventually other schools start to muscle in on the class C kids’ turf.

The plot proceeds like your typical high school gang series, with one fight after another built upon escalating legends of stronger and more notorious punks but with the added twist of exploring the mystery behind the masked TA and the real purpose of the special teaching program that dispatched him and Araki to Kyokuran High in the first place.

If it hasn’t dawned on you by now, there have also been a long line of passing references and spoofs of Tokusatsu heroes in various popular anime that you’ll probably have an easier time noticing from now on: the Great Saiyaman and the infamous Ginyu Force in Dragonball Z are prime examples of a Henshin hero and Super Sentai reference, respectively; Karakuraizer and the Karakura-Raizer team in Bleach are a Henshin Hero and sentai team; the Gachirangers in Mitsudomoe are a Super Sentai team, and the show even goes as far as to make some jokes about Super Sentai fans; Nohmen Rider in Shinryaku! Ika Musume is a Kamen Rider reference; a large number of main characters in the later installations of the Digimon franchise look and act like Henshin Heroes; the Department of City Security Sentai Daitenzin of Excel Saga is a Super Sentai style team. Other than direct parodies, Tokusatsu icons appear quite often in real-world settings, most often during summer festivals as the children’s masks at common game and prize stalls and the many department store rooftop appearances that come up in shows like Sailor Moon and Detective Conan all feature Tokusatsu live-shows that often crop up around major cities as a way to draw in kids and parents on the weekends.

the Great Saiyaman and the infamous Ginyu Force in Dragonball Z are prime examples of a Henshin hero and Super Sentai reference, respectively; Karakuraizer and the Karakura-Raizer team in Bleach are a Henshin Hero and sentai team; the Gachirangers in Mitsudomoe are a Super Sentai team, and the show even goes as far as to make some jokes about Super Sentai fans; Nohmen Rider in Shinryaku! Ika Musume is a Kamen Rider reference; a large number of main characters in the later installations of the Digimon franchise look and act like Henshin Heroes; the Department of City Security Sentai Daitenzin of Excel Saga is a Super Sentai style team. Other than direct parodies, Tokusatsu icons appear quite often in real-world settings, most often during summer festivals as the children’s masks at common game and prize stalls and the many department store rooftop appearances that come up in shows like Sailor Moon and Detective Conan all feature Tokusatsu live-shows that often crop up around major cities as a way to draw in kids and parents on the weekends.

In fact, it may have occurred to you at this point that the Sailor Scouts are in fact a sentai team. I’m sure the hardcore Sailor Moon fans are also aware that there was a live-action series in Japan, which played itself out as a Tokusatsu series in the most true to form manner. What you may not have picked up on is that Tuxedo Kamen/Tuxedo mask is a vague reference to Kamen Rider, but more notably, his later alias, Moonlight Knight, is a reference to an even older Tokusatsu title; the original Henshin Hero, Gekko Kamen (lit. Moonlight Mask), which had its own anime series in the 70s. Moonlight Knight’s design is based on the original design.

And so, at long last you’ve reached the end of the article, dear reader! I hope I’ve managed to give you all just a rough outline of what the Japanese superhero archetype looks like along with a bit of context about those heroes as a cultural icons, and with any luck I’ve gone over something that has managed to turn a head or two and pique your interest. I could keep going with some of the more obscure titles or actually breakdown and start recommending actual Tokusatsu titles, but I think I’ve covered the titles with the largest range of appeal that might interest people and I feel confident in leaving these titles to flagship the generalized Tokusatsu-inspired anime/manga category. Excuse the egregiously long tag list on your way down the rest of the page and please leave a comment about your own impressions/experiences/questions about the live-action Tokusatsu shows you know or are interested/curious about, and/or the anime/manga that reference them!

*Concerning the image of the baby rompers accompanying the previous paragraph (working left to right; top row, then bottom) the patterns are based off of Go Nagai’s manga/anime series Devilman; Dorami and Doraemon from the classic children’s manga/animeDoraemon; Ultraman Seven and the original Ultraman from the ongoing Ultraman tokusatsu series; Son Goku from Akira Toriyama’s Dragonball and Dragonball Z; The generic SHOCKER soldier and Kamen Rider Ichigo from the original season of Kamen Rider; and Akaranger (lit. Redranger) and Momoranger (lit. Pinkranger) from Himitsu Sentai Goranger.

[…] that I hear? It sounds like another super hero article headed this way. This looks like a job for our friendly neighborhood owl-themed crime fighter, […]

[…] a brief explanation of tokusatsu live-action see this article, or alternatively just google or wiki […]

[…] manga was in fact spawned from a commissioned premise for a live-action kids’ show (see my tokusatsu article for more details) which followed the initial publication of the manga by just a few months. Unlike […]

[…] Robo manga was in fact spawned from a commissioned premise for a live-action kids’ show (see my tokusatsu article for more details) which followed the initial publication of the manga by just a few months. Unlike […]