Catching You in His Spell, It’s The Owl in the Rafters!

Welcome back to the Owl in the Rafters 2012 edition, issue #2! Quite some time ago I was told by a certain someone that my articles had a tendency toward leaning on the boyish side of things, sticking mostly to seinen(men 20+) titles and popular shonen(boys 10-19) running in Shueisha’s JUMP line of magazines. In light of this observation I did in fact promise to try and cover more shoujo(girls 10-19) titles, but as of yet I’ve not lived up to that promise.

Earlier this month I tried to roughly sum up the career of Rumiko Takahashi, a now 25 year veteran of the manga industry and one of the most popular female authors/artists of her generation still in publication today. While her work incorporates a good deal of appeal towards female readers however, she has always been published in shonen and seinen targeted magazines rather than marketed as an actual shoujo author. So, although Takahashi was a good start, today I’m cranking things into high gear and tackling the very heart of popular shoujo trends, Mahou Shoujo (lit. “Magical Girl”), from the origins of the genre, to the development of the modern formula, right up to the current running titles.

Now, when I say “Magical Girl” some of you already have a pretty clear image in mind -probably having something at last partly to do with Sailor Moon- but for those unfamiliar with the idea let me give a brief breakdown of the history and key components of the formula. During the 1960s, while Osamu Tezuka was at the height of his career and Japan’s market for animated television programs was still just budding, two titles are credited as being the progenitors of what we now know as the modern Magical Girl.

Now, when I say “Magical Girl” some of you already have a pretty clear image in mind -probably having something at last partly to do with Sailor Moon- but for those unfamiliar with the idea let me give a brief breakdown of the history and key components of the formula. During the 1960s, while Osamu Tezuka was at the height of his career and Japan’s market for animated television programs was still just budding, two titles are credited as being the progenitors of what we now know as the modern Magical Girl.

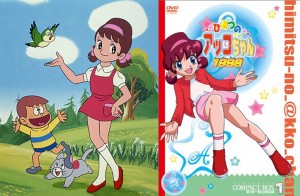

First was Himitsu no Akko-chan (lit. “Akko of Secrets”/”The Secret Akko”), by Fujio Akatsuka and ran from 1962 to 1965 in Shueisha’s young girls magazine, Ribon. Himitsu no Akko-chan was a simple story of a young girl with a special affinity with mirrors through which she is granted a magic mirror that lets her transform into whatever she wants.

First was Himitsu no Akko-chan (lit. “Akko of Secrets”/”The Secret Akko”), by Fujio Akatsuka and ran from 1962 to 1965 in Shueisha’s young girls magazine, Ribon. Himitsu no Akko-chan was a simple story of a young girl with a special affinity with mirrors through which she is granted a magic mirror that lets her transform into whatever she wants.

The story progressed episodically and hinged upon author Akatsuka’s iconic gag humor. The original anime aired in 1969 with a total of 94 episodes. Only a little less than 20 years later in 1988 the TV series was remade with just 61 episodes with two films the following year. Most recently there was a second remake (that makes it the third TV series total) was aired in 1998. Still there is a live action film planned for a 2012 release.

Although Himitsu no Akko-chan is the first manga to feature an example of a Magical Girl the 1966 manga series Mahoutsukai Sally (Lit. “Magic Messenger Sally” but known in English as “Sally the Witch”) first saw animation in 1966, three years before the first Himitsu no Akko-chan anime.

Although Himitsu no Akko-chan is the first manga to feature an example of a Magical Girl the 1966 manga series Mahoutsukai Sally (Lit. “Magic Messenger Sally” but known in English as “Sally the Witch”) first saw animation in 1966, three years before the first Himitsu no Akko-chan anime.

The story was inspired by the unusual success of the Japanese dubbing of the American sitcom, Bewitched and so emulates the same premise of a witch living among normal people while trying to keep the truth about her magic powers a secret. The original 1966 anime ran for 109 episodes over two years and also saw a second series, but a sequel rather than a remake in 1989 followed by a film in 1990.

Apart from just setting the foundations of genre staples like stock transformation scenes, magic trinkets, and the use of magic spell catchphrases these two series neatly set up two of the most common premises in Magical Girl anime as a whole: Set A) the normal girl granted extraordinary powers, and Set B) the extraordinary girl (very frequently a princess) in disguise as a normal person. Oddly neither were ever really adapted into English but both saw fairly successful broadcasts in Italy as well as French and Spanish speaking countries as were many other early Magical Girl anime series.

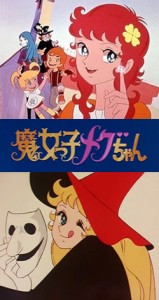

Moving on to the next major development in the genre, the 1974 anime series, Majokko Meg-chan (lit. “Magic Girl Meg”) is often cited as the earliest instance of a Magical Girl series really putting the sitcom hijinks into the backseat in favor of highlighting a more action oriented plot with clearly defined rivals, villains, and magic based combat scenes. As a byproduct of merging elements of what were still at the time considered definitively shounen elements of entertainment the series also had its fair share of the sort of fan-service common to boys’ comics. The story centers around the titular Meg and her struggle to adapt to civilian life in the human world in order to meet certain qualifications as a candidate for Queen of the Witch World.

Moving on to the next major development in the genre, the 1974 anime series, Majokko Meg-chan (lit. “Magic Girl Meg”) is often cited as the earliest instance of a Magical Girl series really putting the sitcom hijinks into the backseat in favor of highlighting a more action oriented plot with clearly defined rivals, villains, and magic based combat scenes. As a byproduct of merging elements of what were still at the time considered definitively shounen elements of entertainment the series also had its fair share of the sort of fan-service common to boys’ comics. The story centers around the titular Meg and her struggle to adapt to civilian life in the human world in order to meet certain qualifications as a candidate for Queen of the Witch World.

While the show does of course play upon the sitcom formula of tackling one silly situation at a time with Meg constantly bumbling and confused about how to act in social situations it does so with more direction and drive than its predecessors, turning the entire show from just a drifting from joke to joke comedy into a kind of coming of age story; Meg gradually learning what it takes, not only to be Queen, but also what it means to be human. This jump in subject matter, from what was once just goofy slice-of-life gags and magical hijinks, turned the genre into a kind of vehicle for young girls to begin identifying, accepting, and dealing with things like domestic abuse, alcoholism, extramarital affairs, depression, and suicide was an enormous leap forward, not merely for the Magical Girl genre but for the animated medium in Japan as a whole.

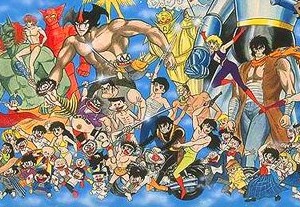

Although it may not be as beneficial a development to the Magical Girl genre, I cannot move on through the time line without touching on Go Nagai’s Cutie Honey. The original 1973 serial publication ran for just one year and only amassed two collected volumes, but the list of adaptations, sequels, and remakes stretches from the first animated TV series in 1973 to the live action drama in 2007 including a film, OVA series, two additional television series, as well as additional manga picked up by other artists.

Although it may not be as beneficial a development to the Magical Girl genre, I cannot move on through the time line without touching on Go Nagai’s Cutie Honey. The original 1973 serial publication ran for just one year and only amassed two collected volumes, but the list of adaptations, sequels, and remakes stretches from the first animated TV series in 1973 to the live action drama in 2007 including a film, OVA series, two additional television series, as well as additional manga picked up by other artists.

For those who don’t know the name, Go Nagai was one of the powerhouses of shounen manga during the 1970s with a hand in over 360 different anime and manga since his professional debut in the 1960s. He was, of course, a shounen author. However so, while Cutie Honey was not truly a girls’ Magical Girl series it did play upon popular elements of the Magical Girl genre and in its own right helped to shape the face of the genre in years to come.

In a typically shounen fashion the premise behind Cutie Honey is that an evil organization, Panther Claw, is causing unrest in the world, but specifically in Japan, and so the hero, Kisaragi Honey, must combat the evil organization using her repertoire of sexy disguises. The disguises are of course all dawned and shed via a transformation device and catchphrase, “Honey Flash!”. Most notable about this is the show’s utilization of heavy Tokusatsu* influence and the slightly controversial scenes of nudity resulting from the regular and frequent costume changes. Again, despite being very distinctly aimed at teenage boys, the overwhelming popularity of the show left a clear image of what was needed to sell the Magical Girl image and so, for better or for worse, Cutie Honey set in motion the dawn of the sexy Magical Girl that has since run rampant throughout the genre.

*For a brief explanation of tokusatsu live-action see this article, or alternatively just google or wiki it.

Most famous of the sexy Magical Girls is, of course, Naoko Takeuchi’s sensational 1991 manga series, Bishoujo Senshi: Sailor Moon (lit. “Beautiful Soldier: Sailor Moon”). However Takeuchi’s hit franchise actually began with a smaller serialized title called Codename: Sailor V which detailed the solo adventures of Minako Aino, a.k.a. Sailor V, a.k.a. Sailor Venus. The manga was moderately successful adding little to no new elements to the established trends of the Magical Girl genre until playing into its sequel/spinoff series, Sailor Moon. I don’t think I really need to elaborate on the details of Sailor Moon, but what is worth noting is that it merged the Magical Girl genre with yet another element of the Tokusatsu live-action genre in developing a sentai team of magical girls with a variety of different personalities, opening a broad new venue for Magical Girl series that has since become a staple of the genre.

Most famous of the sexy Magical Girls is, of course, Naoko Takeuchi’s sensational 1991 manga series, Bishoujo Senshi: Sailor Moon (lit. “Beautiful Soldier: Sailor Moon”). However Takeuchi’s hit franchise actually began with a smaller serialized title called Codename: Sailor V which detailed the solo adventures of Minako Aino, a.k.a. Sailor V, a.k.a. Sailor Venus. The manga was moderately successful adding little to no new elements to the established trends of the Magical Girl genre until playing into its sequel/spinoff series, Sailor Moon. I don’t think I really need to elaborate on the details of Sailor Moon, but what is worth noting is that it merged the Magical Girl genre with yet another element of the Tokusatsu live-action genre in developing a sentai team of magical girls with a variety of different personalities, opening a broad new venue for Magical Girl series that has since become a staple of the genre.

What I personally think is the most interesting part about the Magical Girl genre is that it adheres to an established formula and very rarely deviates, creating an even platform for artists/authors to really push the limits of what personal stylistic twists they can come up with: with the same basic premise nearly all across the board the difference between a popular Magical Girl series and an unopular one really does just boil down to who has the better designs, better art, and better grasp of writing.

The formula, as we know it today, spotlights one or more young teenage girls with access to magical powers via a stereotypically girlish trinket, accessory, or prop thrown into a scenario where she/they must learn to cope with a wide range of common day-to-day scenarios, romantic situations, and/or emotional conflicts in her own life as well as helping those around her through the same.

The episodic encounters each week tackle common dilemmas in young children’s lives, from family trouble, to making friends, dealing with bullies, pursuing personal hobbies, remaining dedicated in spite of hardship, and other scenarios of living up to social responsibilities, coping with emotional distress, and dealing with other people. As an extension of this, in combat oriented Magic Girl series, the monster-of-the-week will almost always be made from or powered by the negative emotions of another human being, requiring the heroines to help the victim come to terms with their unresolved feelings in order to end the episode.

As a result of the popularity of Magical Girls series making strong use of sex appeal the obligatory transformation sequences (very often stock footage) often highlight the nude figure, even if the details of the body are obscured by color choice or conveniently choreographed censoring. In some exceptions the sex appeal is actually skipped on almost entirely in favor of a more classically cute outfit, although this avoidance of sex appeal is nearly exclusive to characters younger than 13 or 14; the odds of seeing a magical girl in modest hero attire over the age of 15 is virtually zero.

As a result of the popularity of Magical Girls series making strong use of sex appeal the obligatory transformation sequences (very often stock footage) often highlight the nude figure, even if the details of the body are obscured by color choice or conveniently choreographed censoring. In some exceptions the sex appeal is actually skipped on almost entirely in favor of a more classically cute outfit, although this avoidance of sex appeal is nearly exclusive to characters younger than 13 or 14; the odds of seeing a magical girl in modest hero attire over the age of 15 is virtually zero.

The transformations are also facilitated by the aforementioned magical trinket/accessory/prop. The object itself is generally a means of selling toys and serves very little purpose in the plot apart from the occasional role as magical macguffin. The accompanying magic words tend to be flowery, poetic, and in some cases bordering on totally meaningless but are repeated throughout the story very often as a part of the stock animation sequences. In exceptionally well conceived series some of these repeated catchphrases will actually embody the underlying moral of the show all together and in turning that moral into an imitate-able phrase better spread the message to its intended, young, impressionable audience.

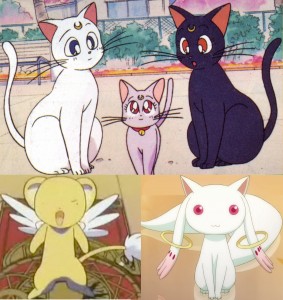

A somewhat unspoken rule of Magical Girls is the necessity of a mascot character: typically some kind of animal, but also quite frequently made up creatures baring strong resemblances to stuffed animals, and always intended to be “cute”. (In some rare occurrences an artist may choose to create an intentionally NOT cute character as a kind of ironic joke, but ultimately these characters usually wind up being thought of as cute anyway.) The mascot character generally takes the role of exposition, as a walking talking kind of user’s guide to the magic girls’ powers. They are nearly always capable of speech, magical themselves in one form or another, but more often than not totally ineffectual in regards to the progression of the plot. These characters, like the magical props are generally just a fail-safe method of cashing in on a successful title with plush-dolls, stickers, stationary, keychains, etc…

A somewhat unspoken rule of Magical Girls is the necessity of a mascot character: typically some kind of animal, but also quite frequently made up creatures baring strong resemblances to stuffed animals, and always intended to be “cute”. (In some rare occurrences an artist may choose to create an intentionally NOT cute character as a kind of ironic joke, but ultimately these characters usually wind up being thought of as cute anyway.) The mascot character generally takes the role of exposition, as a walking talking kind of user’s guide to the magic girls’ powers. They are nearly always capable of speech, magical themselves in one form or another, but more often than not totally ineffectual in regards to the progression of the plot. These characters, like the magical props are generally just a fail-safe method of cashing in on a successful title with plush-dolls, stickers, stationary, keychains, etc…

A short list of popular titles fans in America may be familiar with that I have yet to mention includes: Card Captor Sakura one of the iconic dubbed Magical Girl series of the 1990s, Magic Knight Rayearth by the prestigious veteran art group CLAMP brought the artists’ uniquely elegant artwork to the genre with great success, Wedding Peach an otherwise unremarkable Magical Girl series featuring character designs by Kazuko Tadano (character designer and animation director of the first two seasons of the Sailor Moon anime) with a wedding bride motif, Magical Girl Pretty Sammy the somewhat unusual spin-off of Tenchi Muyo starring the titular alien princess Sasami in an

A short list of popular titles fans in America may be familiar with that I have yet to mention includes: Card Captor Sakura one of the iconic dubbed Magical Girl series of the 1990s, Magic Knight Rayearth by the prestigious veteran art group CLAMP brought the artists’ uniquely elegant artwork to the genre with great success, Wedding Peach an otherwise unremarkable Magical Girl series featuring character designs by Kazuko Tadano (character designer and animation director of the first two seasons of the Sailor Moon anime) with a wedding bride motif, Magical Girl Pretty Sammy the somewhat unusual spin-off of Tenchi Muyo starring the titular alien princess Sasami in an  alternate universe, totally unrelated to the story and plot of any of the Tenchi Muyo series (stranger yet, the spin-off got its own spinoff, Sasami: Magical Girls Club, which is confusingly a more by-the-books Magical Girl series than its predecessor.), Tokyo Mew Mew (localized in the US as Mew Mew Power) which starred an animal themed team of magical girls and pushed an environmentalist message with its story, Mermaid Melody Pichi Pichi Pitch a magical girl series centered around a cast of mermaids living among humans with some arguably terrible yet charming writing, and Ojamajo DoReMi franchise (although only one season was ever dubbed and released in the US as Magical DoReMi) a cute return to the basics of the genre starring a young team of pointy hat wearing, broom stick riding, preteen and totally non-sexualized witches tackling character driven plots as opposed to constantly combatting evil. In a genuinely surprising twist, over the course of its 4 seasons, the show wrestles with some unusually heavy subjects for what is still very much a kids’ show, involving the responsibilities of parenthood (and actually depicts the parents as characters and not just faceless, cold hearted, work-a-holic, scapegoats), a child hospitalized with cancer, and a family torn apart by the death of an unborn child.

alternate universe, totally unrelated to the story and plot of any of the Tenchi Muyo series (stranger yet, the spin-off got its own spinoff, Sasami: Magical Girls Club, which is confusingly a more by-the-books Magical Girl series than its predecessor.), Tokyo Mew Mew (localized in the US as Mew Mew Power) which starred an animal themed team of magical girls and pushed an environmentalist message with its story, Mermaid Melody Pichi Pichi Pitch a magical girl series centered around a cast of mermaids living among humans with some arguably terrible yet charming writing, and Ojamajo DoReMi franchise (although only one season was ever dubbed and released in the US as Magical DoReMi) a cute return to the basics of the genre starring a young team of pointy hat wearing, broom stick riding, preteen and totally non-sexualized witches tackling character driven plots as opposed to constantly combatting evil. In a genuinely surprising twist, over the course of its 4 seasons, the show wrestles with some unusually heavy subjects for what is still very much a kids’ show, involving the responsibilities of parenthood (and actually depicts the parents as characters and not just faceless, cold hearted, work-a-holic, scapegoats), a child hospitalized with cancer, and a family torn apart by the death of an unborn child.

Over the years the easily identifiable and mostly unaltered formula has become not just well recognized as a trend but also the subject of various parodies and spoofs, often somewhat vulgar or crude in nature as an intentional contrast to the genre’s expected delicateness and purity. Several such parody series include: Bokusatsu Tenshi Dokuro-chan and Witch Punie-chan(manga)/Dai Mahou Touge(anime) both of which use excessive violence and absurdist humor in stark contrast to very cliche looking magical girl heroines. Another example would be Zettai Seigi Love Pheromone & Akahori Gedou Hour Rabuge a dual segment show involving a pair of useless and disaster prone adult magical girls who tend to do more damage than they ever prevent, and a family of unintentionally kind hearted magical girls who continuously try and fail to villainously destroy the world, generally saving lives and doing good deeds in the process. There is also the Nurse Witch Komugi and Nurse Witch Komugi-chan Magicarte Z OVAs which are parodies, spin-offs, and technically sequels of the anime SoulTaker, starring one of its very minor support characters as the titular magic nurse. Finally, one very unique kind of parody is Power Puff Girls Z, a fairly controversial anime series with Western audiences that attempts to recreate Craig McCracken’s original Powerpuff Girls premise in a Japanese context. To clarify, it utilizes Japanese anime, tokusatsu, and kaiju cliches along with references to otaku culture in a series about three super powered girls rather than use American comicbooks, cartoons, and American geek culture references like McCracken’s original Powerpuff Girls cartoon did. More often than not Western audiences are thrown into fits of petty nerd rage at the unexpectedly drastic differences between the two shows. The change is, of course, intentional and more than likely meant to poke fun at the bizarre changes inherent to localization of foreign comedy.

Over the years the easily identifiable and mostly unaltered formula has become not just well recognized as a trend but also the subject of various parodies and spoofs, often somewhat vulgar or crude in nature as an intentional contrast to the genre’s expected delicateness and purity. Several such parody series include: Bokusatsu Tenshi Dokuro-chan and Witch Punie-chan(manga)/Dai Mahou Touge(anime) both of which use excessive violence and absurdist humor in stark contrast to very cliche looking magical girl heroines. Another example would be Zettai Seigi Love Pheromone & Akahori Gedou Hour Rabuge a dual segment show involving a pair of useless and disaster prone adult magical girls who tend to do more damage than they ever prevent, and a family of unintentionally kind hearted magical girls who continuously try and fail to villainously destroy the world, generally saving lives and doing good deeds in the process. There is also the Nurse Witch Komugi and Nurse Witch Komugi-chan Magicarte Z OVAs which are parodies, spin-offs, and technically sequels of the anime SoulTaker, starring one of its very minor support characters as the titular magic nurse. Finally, one very unique kind of parody is Power Puff Girls Z, a fairly controversial anime series with Western audiences that attempts to recreate Craig McCracken’s original Powerpuff Girls premise in a Japanese context. To clarify, it utilizes Japanese anime, tokusatsu, and kaiju cliches along with references to otaku culture in a series about three super powered girls rather than use American comicbooks, cartoons, and American geek culture references like McCracken’s original Powerpuff Girls cartoon did. More often than not Western audiences are thrown into fits of petty nerd rage at the unexpectedly drastic differences between the two shows. The change is, of course, intentional and more than likely meant to poke fun at the bizarre changes inherent to localization of foreign comedy.

On several occasions magical girl series are used as the iconic “current hit anime” in anime and manga titles involving otaku characters or otherwise satirizing the anime industry and its fanbase. More impressive still is that very often these satirical sketches garner enough popularity to merit their own legitimate anime series; example of this include: Getsumen to Heiko Mina a magical girl parody in the Densha Otoko live-action television drama (not to be confused with the unaffiliated production of the live-action Densha Otoko:Train Man film) that got its own 11 episode TV series with 2 DVD exclusive bonus episodes, Puni Puni Poemi from Excel Saga both by famed director Watanabe Shinichi (aka NabeShin) that satirically mocks conventions of the Magical Girl genre among many many other anime cliches in a 2 episode OVA, and to a lesser degree Kujibiki Unbalance from Genshiken which is a parody combining all popular anime trends into a single series, with the Magical Girl elements playing only a minor stylistic role in the course of the 12 episode long television series.

On several occasions magical girl series are used as the iconic “current hit anime” in anime and manga titles involving otaku characters or otherwise satirizing the anime industry and its fanbase. More impressive still is that very often these satirical sketches garner enough popularity to merit their own legitimate anime series; example of this include: Getsumen to Heiko Mina a magical girl parody in the Densha Otoko live-action television drama (not to be confused with the unaffiliated production of the live-action Densha Otoko:Train Man film) that got its own 11 episode TV series with 2 DVD exclusive bonus episodes, Puni Puni Poemi from Excel Saga both by famed director Watanabe Shinichi (aka NabeShin) that satirically mocks conventions of the Magical Girl genre among many many other anime cliches in a 2 episode OVA, and to a lesser degree Kujibiki Unbalance from Genshiken which is a parody combining all popular anime trends into a single series, with the Magical Girl elements playing only a minor stylistic role in the course of the 12 episode long television series.

With all that on the table, I’d like to touch on some fairly recent magical girl series that have really tried to bend the rules, push the limitations of, or just taken the extra effort to polish up the Magical Girl formula to create something refreshingly new, but still familiar.

To start I’ll just quickly point out that Princess Tutu is a prime example of a well polished and fine tuned Magical Girl series that plays out all of the genre’s formulaic points as one would expect but with all the grace and style befitting a series with a strong and (mostly) well researched ballet theme with a focus on various classical ballet stories as well as its own original plot that takes a generally unexpected turn for the dramatic during the second half of the series. Since MollyBibbles has already done an article covering Princess Tutu and in more detail than I’d have room for here, I’ll point you in that direction and move along.

To start I’ll just quickly point out that Princess Tutu is a prime example of a well polished and fine tuned Magical Girl series that plays out all of the genre’s formulaic points as one would expect but with all the grace and style befitting a series with a strong and (mostly) well researched ballet theme with a focus on various classical ballet stories as well as its own original plot that takes a generally unexpected turn for the dramatic during the second half of the series. Since MollyBibbles has already done an article covering Princess Tutu and in more detail than I’d have room for here, I’ll point you in that direction and move along.

Moving right along into more experimental territory a popular recent title is Puella Magi Madoka Magica. A 12 episode anime original with a three part film series in the works, Puella Magi Madoka Magica has garnered much attention as the only recent example of a deconstruction of the genre and was particularly popular because it took itself more seriously, as opposed to the comical nature of some previous deconstruction series like the aforementioned mentioned Bokusatsu Tenshi Dokuro-chan and Dai Mahou Touge. Although, to be technical, the series is less an actual deconstruction and more just a massive subversion.

Moving right along into more experimental territory a popular recent title is Puella Magi Madoka Magica. A 12 episode anime original with a three part film series in the works, Puella Magi Madoka Magica has garnered much attention as the only recent example of a deconstruction of the genre and was particularly popular because it took itself more seriously, as opposed to the comical nature of some previous deconstruction series like the aforementioned mentioned Bokusatsu Tenshi Dokuro-chan and Dai Mahou Touge. Although, to be technical, the series is less an actual deconstruction and more just a massive subversion.

What I mean by that is that a “deconstruction” would normally take a standard idea and follow it through to a logical but normally swept under the rug conclusion. Madoka doesn’t so much do this as is does play out most of the formula without alteration, and then makes up its own little twists independent to the genre’s cliches, thus subverting the formula rather than actually playing with it. The biggest key in this of course being the now famous Kyubei/Q-bei mascot character and the nature of the contract it makes with the shows’ magical girls.

I don’t want to spoil things, which is particularly hard with a series that sells itself on plot twists, so I’ll just say that all plot twists aside, the series takes some very interesting artistic cues in terms of design that alone make it worth checking out, although the magical girl designs themselves aren’t particularly cute, uniquely meaningful, or even consistent with each other.

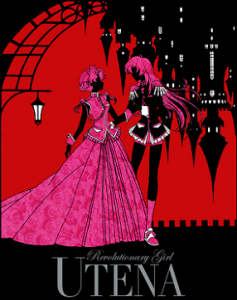

Of course Puella Magi Madoka Magica isn’t the first series to play with the Magical Girl formula in a serious fashion. The most notable culprit of that would be Revolutionary Girl Utena, a 1997 anime series considered the title’s canon, over it’s simultaneously developed 1996 manga series. The series places the titular heroine, Utena Tenjou, in the middle of an elaborate apocalyptic conspiracy centered around a prestigious private academy that she attends. One very interesting stylistic choice is in making the heroine a kind of gentlemanly lady, sword duels and all; the lynchpin to her character motivation being that she strives to emulate a prince she met in her childhood, despite being a woman and as opposed to trying to be a princess-like character.

Of course Puella Magi Madoka Magica isn’t the first series to play with the Magical Girl formula in a serious fashion. The most notable culprit of that would be Revolutionary Girl Utena, a 1997 anime series considered the title’s canon, over it’s simultaneously developed 1996 manga series. The series places the titular heroine, Utena Tenjou, in the middle of an elaborate apocalyptic conspiracy centered around a prestigious private academy that she attends. One very interesting stylistic choice is in making the heroine a kind of gentlemanly lady, sword duels and all; the lynchpin to her character motivation being that she strives to emulate a prince she met in her childhood, despite being a woman and as opposed to trying to be a princess-like character.

Other than the Magical Girl genre, the series does, in fact, play with a wide range of other anime cliches, both in story telling and in art and production. More famously however the story also makes heavy references to real world literature, most prominently European authors classical Roman mythos, and both Freudian and Jungian psychology. Very often lauded as “the Neon Genesis Evangelion of Shoujo”, apart from presenting a distinctly bittersweet kind of coming-of-age story, the series makes a point of very thoroughly exploring the real limits of the conventional formula without trying to outright break down established archetypes or trying to be purely inventive. Some very stylish design choices and a genuinely complementary soundtrack that really does its part in setting the mood and pace for the animation and not just arbitrary or ineffectual auxiliary noise.

Another notable magical girl series that bends the rules is Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha. As I mentioned before, the modern trends in Magical Girl anime may still target young girls as their primary audience, but the producers, artists, and writers are all very much aware of the outlying audience of older males and often make small concessions for that audience. Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha takes this to an extreme and creates a magical girl anime aimed directly at that older male audience.

Another notable magical girl series that bends the rules is Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha. As I mentioned before, the modern trends in Magical Girl anime may still target young girls as their primary audience, but the producers, artists, and writers are all very much aware of the outlying audience of older males and often make small concessions for that audience. Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha takes this to an extreme and creates a magical girl anime aimed directly at that older male audience.

I won’t bog things down with the show’s jargon, but the plot starts off as a perfectly average magical girl series involving some things that the villains want and the heroes need to keep them from getting a hold of, with just a touch of sci-fi thrown in, touching on all the cliches and not rocking the boat for about 10 episodes or so before the accumulated supporting cast begins to shake things up. While the entire show is by no means revolutionary, seeing a magical girl series play out more like a light mecha show was a refreshing and interesting twist.

The franchise started as the anime adaptation of a visual novel spin-off of an ero-game. The show itself is however perfectly clean, (mostly) child friendly, and work safe in regards to content. The franchise has spawned three animated television series, the self titled Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha, Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha As, and Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha StrikerS as well as a film series still under way, including the 2010 Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha The MOVIE 1st, which retells a reduced version of the events of the first TV series, and the upcoming Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha The MOVIE 2nd A’s which, of course, does the same for the second TV series and is scheduled for release sometime in 2012.

I could really just keep going with this forever but for both our sakes I’m going to stop and let you go. I’d like to thank you and congratulate you for having sat through my cascade of skirts, rainbows, sparkles, and magic. and I do hope you’ve learned a little something, or at least taken away some small amount of new appreciation for the Magical Girl genre from this article. I encourage you to poke around and dig up more magical girl series on your own, because there are so many out there worth watching/reading.

For the sake of keeping this article as compact as possible, I tried (no, really, I did…) to only list titles with some pertinence to you as an English speaking audience and to the genre as a whole, but I could have filled as much space with premises and plot synopsis alone. There are a number of shows I would have loved to cover but may have to save for another day. (heck, I didn’t even have room to touch on the Magical Idol sub-genre.) And just to be clear, this recommendation goes for guys just as strongly as it does for girls!

For those who aren’t so enthusiastic in diversifying their range of different demographics however, I can at least promise that my little shoujo stint is done for the time being. I’ll be taking the first week of February as a short break from the drama, romance, and cutesy-wootsy to keep Valentines Day from turning this into a full season long shoujo marathon.

As I was reading I was actually thinking you might leave Utena out, but was happy to see a mention of it.

Magical Girl and Sailor Moon go hand in hand, mostly in the Western market, so this will be nice for people who want to see other series that aren’t necessarily too girly. I think for some Magical Girl can simply equal too feminine, which is a shame when you consider some of the moments in several shows as they turn darker or reach their climax (whether the season, episode, or entire series).

“The boys will love the non-stop action!” <--- A cookie for anyone who gets that.

I was actually really looking forward to going on a little fanboy-ish rant about the animation in Heart Catch Pretty Cure among other things, but I couldn’t find the space to fit it in neatly. Utena was one series I wouldn’t let slide though, even if I didn’t have the space to say much about it.

[…] a significantly more personal, albeit blatantly exaggerated flare to the online characters. In my Magical Girl article a few weeks back I mentioned a spinoff series that had initially been a show within a show, that […]