Overcompensating with the Owl in the Rafters

Welcome to a special manly compensatory update of the Owl in the Rafters! As promised, in light of two weeks of girly updates and an upcoming lovey-dovey valentines day special, I’m taking this week to motivate you to man up and muse over some macho manga, manly anime, and virile video games, so step back and watch me flex my biographer biceps, my anime adductors, and my gamer glutes as I tackle all manner of masculine media. In case I lost you in the alliterative deluge, I’m talking about covering manga, anime, and maybe a game or two with notoriously over the top “manly” nonsense; hot blooded heroes, raw willpower overcoming the forces of evil and physics, and muscles coming out of each ear as far as the eye can see.

Welcome to a special manly compensatory update of the Owl in the Rafters! As promised, in light of two weeks of girly updates and an upcoming lovey-dovey valentines day special, I’m taking this week to motivate you to man up and muse over some macho manga, manly anime, and virile video games, so step back and watch me flex my biographer biceps, my anime adductors, and my gamer glutes as I tackle all manner of masculine media. In case I lost you in the alliterative deluge, I’m talking about covering manga, anime, and maybe a game or two with notoriously over the top “manly” nonsense; hot blooded heroes, raw willpower overcoming the forces of evil and physics, and muscles coming out of each ear as far as the eye can see.

Other than giving a little breakdown of the plot and premise on top of a little background as I usually do, I’d like to grade this week’s selection of titles on a 1-to-5 scale of manliness based upon manly art, design, characters, story, and of course action. So, keep an eye out for my flex count at the end of each series overview. Don’t worry, you’ll know it when you see it.

So, to get things oiled up, my first pick is the second entry in the gag comedy and international super hero parody series, Kinnikuman (lit. “Muscleman”), more likely recognized in America for the localized identity Ultimate Muscle: The Kinnikuman Legacy. The series as a whole and the story of its two major protagonists centers on a world where all popular super heroes are real. (or at least some vague parody equivalents of them) In such a world there exists a planet of beings from whom all great supermen both Japanese, American, and otherwise are supposedly derived, the Muscle Planet.

So, to get things oiled up, my first pick is the second entry in the gag comedy and international super hero parody series, Kinnikuman (lit. “Muscleman”), more likely recognized in America for the localized identity Ultimate Muscle: The Kinnikuman Legacy. The series as a whole and the story of its two major protagonists centers on a world where all popular super heroes are real. (or at least some vague parody equivalents of them) In such a world there exists a planet of beings from whom all great supermen both Japanese, American, and otherwise are supposedly derived, the Muscle Planet.

In a bizarre parody of Superman’s origin story, Ultraman’s iconic head blade, and the costumed antics of Japanese pro-wrestling blended together with the classic comedic stylings of a 1970s gag manga, the original 1979 series began with the first Kinnikuman, son of the King of Muscle Planet, accidentally abandoned on Earth and raised as a (more or less) normal human being before pursuing a career as a super hero. Among all the great heroes of Earth however, Kinnikuman is the one notorious failure, blessed with an Ultraman-like power to grow to enormous sizes and combat giant monsters, yet often unable to defeat even the weakest of opponents. The early series starts as just a comedy series playing up common gag scenarios as well as a variety of super hero jokes centered around the life of the unlucky, unattractive, and unsuccessful protagonist, but around 30 chapters in shifts gears towards being a sports series with a world wide giant hero wrestling competition filled with hilarious stereotypes representing various nations.

Among all the great heroes of Earth however, Kinnikuman is the one notorious failure, blessed with an Ultraman-like power to grow to enormous sizes and combat giant monsters, yet often unable to defeat even the weakest of opponents. The early series starts as just a comedy series playing up common gag scenarios as well as a variety of super hero jokes centered around the life of the unlucky, unattractive, and unsuccessful protagonist, but around 30 chapters in shifts gears towards being a sports series with a world wide giant hero wrestling competition filled with hilarious stereotypes representing various nations.

(It may be hard not to mix them up but those are the super heroes on the bottom, the wrestlers in the top left corner, and the joke to the right.)

The plot teeters back and forth between sports competitions, climbing fight ladders, and the occasional return to episodic super heroics but always with a healthy dose of comedy in the mix. Over three hundred chapters later, the super wrester angle with a comedy twist proved more popular than the comedy angle with the hero twist and the first series ends as an outright action series. When the second series picked the franchise back up it begins the story of a second generation of intergalactic, international super hero wrestlers training to take the place of their predecessors and defeat an evil wrestling league with a distinctly American pro-wrestling flavor.

Some of you may be just a little too young or too new to anime to remember it, but there was a brief time during the early 2000s when the company known as 4kids actually wasn’t infamous for producing over-localized garbage, but pretty darn reliable for releasing localized comedic gold. I’ve mentioned one such instance when I briefly covered Fighting Foodons in a different themed article, but Ultimate Muscle may be 4kids’ finest achievement, second only to milking the Pokémon franchise half to death.

Some of you may be just a little too young or too new to anime to remember it, but there was a brief time during the early 2000s when the company known as 4kids actually wasn’t infamous for producing over-localized garbage, but pretty darn reliable for releasing localized comedic gold. I’ve mentioned one such instance when I briefly covered Fighting Foodons in a different themed article, but Ultimate Muscle may be 4kids’ finest achievement, second only to milking the Pokémon franchise half to death.

Other than just dodging some of the more obvious racial issues, 4kids managed to rework a bulk of the script in Ultimate Muscle to something genuinely funny that managed to not only replace the uniquely Japanese sense of humor with an appropriately Western equivalent, but even managed to shoehorn in an astonishing amount of crude and borderline adult humor, as well as a large number of pop culture references that outright soared over the heads of the intended audience in place of what had otherwise been bland, and generic shounen action series banter. Quite a drastic difference from the company’s more recent reputation for excessive censorship.

Other than just dodging some of the more obvious racial issues, 4kids managed to rework a bulk of the script in Ultimate Muscle to something genuinely funny that managed to not only replace the uniquely Japanese sense of humor with an appropriately Western equivalent, but even managed to shoehorn in an astonishing amount of crude and borderline adult humor, as well as a large number of pop culture references that outright soared over the heads of the intended audience in place of what had otherwise been bland, and generic shounen action series banter. Quite a drastic difference from the company’s more recent reputation for excessive censorship.

I’d like to point out most prominently the change of the character Gazelleman, a fairly normal character with no particularly special comedic qualities into Dik-dik Van Dik, combining a breed of tiny deer native to parts of Africa and the Middle East with American 1960s TV celebrity Dick Van Dyke, effectively creating a joke that no child watching would have understood and so could only have conceivably been intended to solicit giggles over the word Dik being spoken in rapid succession in regular conversation: He was also voiced by Eric Stuart, who I’ll just assume by this point is best known as the voice of Seto Kaiba. To hammer the point home however, this is 4kids we’re talking about, ADDING the word “dik” to a script among countless other not so subtle word games that get thrown around like the writers were playing a game of monkey in the middle with their audience.

I’d like to point out most prominently the change of the character Gazelleman, a fairly normal character with no particularly special comedic qualities into Dik-dik Van Dik, combining a breed of tiny deer native to parts of Africa and the Middle East with American 1960s TV celebrity Dick Van Dyke, effectively creating a joke that no child watching would have understood and so could only have conceivably been intended to solicit giggles over the word Dik being spoken in rapid succession in regular conversation: He was also voiced by Eric Stuart, who I’ll just assume by this point is best known as the voice of Seto Kaiba. To hammer the point home however, this is 4kids we’re talking about, ADDING the word “dik” to a script among countless other not so subtle word games that get thrown around like the writers were playing a game of monkey in the middle with their audience.

Considering that the final product of the American Ultimate Muscle that ran on the Fox Box was filled with random wacky slapstick, outdated pop culture references, deliberately goofy voice acting, some liberal use of meta-commentary, and all around nonsensical and crude humor, Ultimate Muscle was basically a “Kinnikuman the Abridged Series” 4 years before LittleKuriboh was ever a name anyone knew, and 5 years before Y!tAS actually got around to being any good. Subsequently that means 5 years before the bandwagon’s baggage capacity got maxed out as every talentless anime fan under the sun and their little brother decided to grasp the wrong end of the comedic s(ch)tick and started the long long line of god awful “abridged” series out there today, most of which STILL don’t seem to understand the basic definition of the word “abridged”. That’s also 6 years before Team Four Star got around to making the only other decent abridged series out there.

So, when it all really boils down, I give Ultimate Muscle (That is Ultimate Muscle in particular and not the original Kinnikuman or the Japanese Kinnikuman Nisei) a 3 out of 5 flexes on the muscle scale for manly action, manly character design, and story that shifts between goofy comedy and manly coming of age tale. The art is acceptable and muscles abound, but when it comes right down to it, nothing special, and while the characters are extraordinarily amusing they tend to fulfill their roles as comedians before their roles as heroes.

Inching slowly away from the comedic end of things the next title I want to cover is Baki the Grappler, a series notorious for its art. Originally run in Weekly Shounen Champion starting in 1991, the series has been ongoing since but divided into three separate titles: Baki the Grappler, Baki (aka New Grappler Baki to help avoid confusion), and the ongoing Baki: Son of Ogre. Of the three, only the first installment, Baki the Grappler, has seen animation, one OVA and two 24 episode television series, both of which were dubbed and released in NA by Funimation but as a single 48 episode long series under the title Baki the Grappler.

Inching slowly away from the comedic end of things the next title I want to cover is Baki the Grappler, a series notorious for its art. Originally run in Weekly Shounen Champion starting in 1991, the series has been ongoing since but divided into three separate titles: Baki the Grappler, Baki (aka New Grappler Baki to help avoid confusion), and the ongoing Baki: Son of Ogre. Of the three, only the first installment, Baki the Grappler, has seen animation, one OVA and two 24 episode television series, both of which were dubbed and released in NA by Funimation but as a single 48 episode long series under the title Baki the Grappler.

The story follows the titular hero, Baki Hanma, a young man born and raised waist deep in martial arts. His father is, Yujiro “The Ogre”, a man famed as the world’s strongest martial artist, and the man that Baki has sworn to defeat in combat, take the title of, and ultimately kill with his own two hands. To that end, Baki has departed from the traditional realm of martial arts and developed his own style that incorporates both existing fighting styles as well as mimicry of animal behavior in the attempt to trump his father’s wide range of martial arts mastery.

The story follows the titular hero, Baki Hanma, a young man born and raised waist deep in martial arts. His father is, Yujiro “The Ogre”, a man famed as the world’s strongest martial artist, and the man that Baki has sworn to defeat in combat, take the title of, and ultimately kill with his own two hands. To that end, Baki has departed from the traditional realm of martial arts and developed his own style that incorporates both existing fighting styles as well as mimicry of animal behavior in the attempt to trump his father’s wide range of martial arts mastery.

The plot of the series is expectedly straight forward: Baki seeks out and fights stronger and stronger opponents, going through all the necessary power up and preparation training before each major fight. As Baki steam rolls his way through fights we also get little glimpses into his personal life, learning why he wants to kill his father, that he has a half-brother with similar goals and aspirations, and just what becomes of Baki’s mother, a woman caught in the conflict of two inhumanly powerful men.

The plot of the series is expectedly straight forward: Baki seeks out and fights stronger and stronger opponents, going through all the necessary power up and preparation training before each major fight. As Baki steam rolls his way through fights we also get little glimpses into his personal life, learning why he wants to kill his father, that he has a half-brother with similar goals and aspirations, and just what becomes of Baki’s mother, a woman caught in the conflict of two inhumanly powerful men.

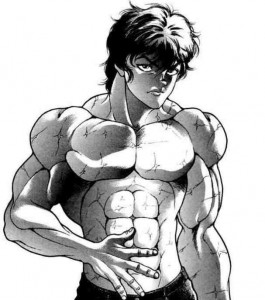

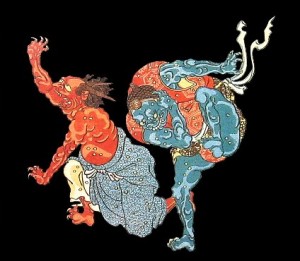

Aside from being a popular, long running and ongoing manga series, I did mention that it has built some notoriety for its art style. Artist Keisuke Itagaki is himself a martial artist as well as a former serving member of the Japanese Self-Defense Force, but his depiction of the human anatomy has very often come under criticism for his wildly exaggerated musculature. His art style is consistent enough in its bizarre proportions and muscular definition that I can only assume it to be entirely intentional, as his illustrative work in the novel series Ga-Rou-Den would suggest. Personally I would like to think that his art style is a throw back to the look of classical Japanese Ukiyo-e wood block print and their depiction of samurai as well as spirits and monsters.

Aside from being a popular, long running and ongoing manga series, I did mention that it has built some notoriety for its art style. Artist Keisuke Itagaki is himself a martial artist as well as a former serving member of the Japanese Self-Defense Force, but his depiction of the human anatomy has very often come under criticism for his wildly exaggerated musculature. His art style is consistent enough in its bizarre proportions and muscular definition that I can only assume it to be entirely intentional, as his illustrative work in the novel series Ga-Rou-Den would suggest. Personally I would like to think that his art style is a throw back to the look of classical Japanese Ukiyo-e wood block print and their depiction of samurai as well as spirits and monsters.

What all boils down to is a manly art style, depicting all around manly characters, doing manly things in a manly story, but with just a twinge of unintentional humor as a consequence of the bizarre anatomy. A hearty four of five flexes on the muscle scale for all around manly excellence.

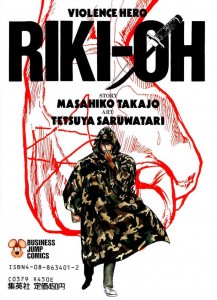

Sticking to the unintentionally comedic slant of things but nudging the manly slider a little away from to totally insane end of the scale, I’d like to say just a little something on Masahiko Takajo’s Violence Hero: Riki-Oh. A fairly popular manga with two English release OVAs Riki-Oh is generally better remembered as the source material for a notoriously bad hong kong live action film adaptation, Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky.

Sticking to the unintentionally comedic slant of things but nudging the manly slider a little away from to totally insane end of the scale, I’d like to say just a little something on Masahiko Takajo’s Violence Hero: Riki-Oh. A fairly popular manga with two English release OVAs Riki-Oh is generally better remembered as the source material for a notoriously bad hong kong live action film adaptation, Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky.

In all adaptations the story follows its eponymous main character and his survival in a post apocalyptic world as he breaks his way out of a high security prison after slaughtering a number of yakuza members in retribution for the death of a child (the role is fulfilled by his girlfriend in the movie), a conflict that leaves him with five bullets permanently embedded in his body.

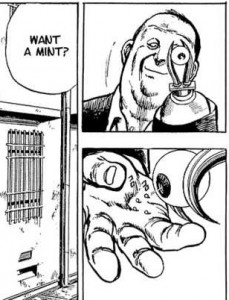

I really wish I could show some of the action of the manga, seeing as it is the best part of the manga, but the whole selling point to the action has always been the absurd and grotesque gore and violence. Even beyond the villains’ extreme measures in torturing and brutalizing the many innocent victims that Riki tends to avenge rather than rescue Riki himself displays time and time again his own disgustingly inhuman strength as he literally punches holes in people, blowing chunks of bone and guts across the pages. There are, of course, other less practical uses of bizarre body horror, such as the prison warden who keeps breath mints in his glass eye, so in lieu of any inappropriate gore I’ll just leave you with that.

I really wish I could show some of the action of the manga, seeing as it is the best part of the manga, but the whole selling point to the action has always been the absurd and grotesque gore and violence. Even beyond the villains’ extreme measures in torturing and brutalizing the many innocent victims that Riki tends to avenge rather than rescue Riki himself displays time and time again his own disgustingly inhuman strength as he literally punches holes in people, blowing chunks of bone and guts across the pages. There are, of course, other less practical uses of bizarre body horror, such as the prison warden who keeps breath mints in his glass eye, so in lieu of any inappropriate gore I’ll just leave you with that.

Frankly the story is hardly entertaining by itself and the action while fun boarders on too goofy even to enjoy. Some of the more inventive approaches to the gory action are strangely admirable in their own way, however. The classically hot-blooded men’s manga style shows itself not only in the art but in the characters and the many side character backstories of good honest men trying to find a place to live peacefully in a corrupt world. There’s really not much to be said about the manga or the film’s impact or history as there’s next to nothing to go over. So, while brief, my assessment of Riki-Oh gives it a flex for character, flex for action, and flex for art and design for another four out of five score.

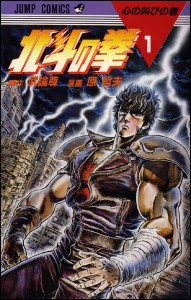

I think it is fair to say that I can’t really end this article without bringing up Hokuto no Ken, A.K.A. Fist of the North Star, or Dragon Ball Z in some capacity. So, considering that more or less every/any anime fan out there worth his/her spit now’days knows Dragon Ball Z, whether it was something he/she enjoyed or not, between the two of them I’ll have to pick Fist of the North Star.

I think it is fair to say that I can’t really end this article without bringing up Hokuto no Ken, A.K.A. Fist of the North Star, or Dragon Ball Z in some capacity. So, considering that more or less every/any anime fan out there worth his/her spit now’days knows Dragon Ball Z, whether it was something he/she enjoyed or not, between the two of them I’ll have to pick Fist of the North Star.

Originally run in Fresh Jump as a one-shot by Tetsuo Hara in 1983, and run in Weekly Jump as a serial title that same year with help from manga author Bronson, Fist of the North Star quickly grew to be one of Jump’s flagship titles during the 80s along side other big hits like Dr.Slump, Captain Tsubasa, Dragon Ball, Saint Seiya, City Hunter, and Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure. (I will come back to that last one in particular a bit later.)

The Fist of the North Star franchise and its many spinoffs and side-stories take place in a Mad Max inspired post apocalyptic 199X and generally center around the kung-fu film heroics of the last heir to a deadly, ancient, and mythical martial arts style, Hokuto Shinken, as he wanders the barren wastelands, dispensing brutal justice on the many warlords that have taken control of the grim future as he goes.

The Fist of the North Star franchise and its many spinoffs and side-stories take place in a Mad Max inspired post apocalyptic 199X and generally center around the kung-fu film heroics of the last heir to a deadly, ancient, and mythical martial arts style, Hokuto Shinken, as he wanders the barren wastelands, dispensing brutal justice on the many warlords that have taken control of the grim future as he goes.

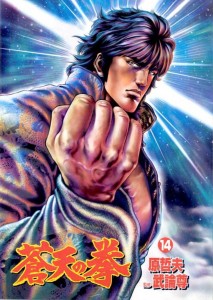

Rather than go into any real depth about Fist of the North Star itself, or even the 2004 OVA New Fist of the North Star I’d like to touch on closely related entry in Tetsuo Hara’s library of work: Fist of the Blue Sky. As the title would hint at, Fist of the Blue Sky is indeed related to Fist of the North Star, a prequel in fact.

Tracing back the lineage of the Hokuto Shinken martial arts school to 1930s Shanghai China, Fist of the Blue Sky saddles follows the uncle (older brother of the father) of Fist of the North Star‘s protagonist, Kenshiro, also named Kenshiro, Kenshiro Kasumi. (The …North Star Kenshiro is in fact named after his uncle, the …Blue Sky Kenshiro.)

Tracing back the lineage of the Hokuto Shinken martial arts school to 1930s Shanghai China, Fist of the Blue Sky saddles follows the uncle (older brother of the father) of Fist of the North Star‘s protagonist, Kenshiro, also named Kenshiro, Kenshiro Kasumi. (The …North Star Kenshiro is in fact named after his uncle, the …Blue Sky Kenshiro.)

Kasumi is a retired assassin once wrapped up in Shanghai’s elaborate criminal underground as an assassin without peer. Sick of the callous politics of the Triad’s gang wars, Kasumi retreated to Tokyo Japan where he settled down as a university professor for a time until he happens upon a chance reunion with an old friend at the start of the story and learns that virtually all of his friends in Shanghai have been slaughtered. Thus begins Kasumi’s vendetta rampage over the Shanghai underworld.

With the original Fist of the North Star series having already drawn heavily upon cliches, archetypes, and other elements of the classic 1970s kung-fu film formula, Fist of the Blue Sky quite predictably sticks to the same track, but cranks the volume up a few notches. Like the original series Fist of the Blue Sky also hosts a large cast of inhumanly large, muscular, and down right unusually shaped villains on top of its exotic selection of fictional and fantastic martial arts styles.

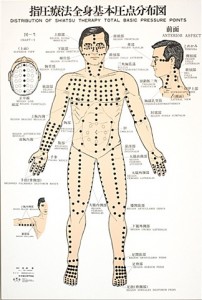

If you didn’t already know, the entire gimmick of the Hokuto Shinken martial arts style is that it takes the concept of qi and bodily energies behind acupuncture to what I’m reluctant to call the “logical” extremities of its use in fiction. Where as real world belief in qi flow suggests that if the direction and path of flow as well as pressure, and release points of this mystical energy can be understood, they can then be used, and/or abused to promote physical wellness as well as sickness, cramps, paralysis, and other internal effects. Hokuto Shinken’s fictional applications force one fighter’s qi into the pressure point(s) of his opponents, causing an immediate overflow. The ultimate effect? Exploding heads. Exploding heads everywhere.

If you didn’t already know, the entire gimmick of the Hokuto Shinken martial arts style is that it takes the concept of qi and bodily energies behind acupuncture to what I’m reluctant to call the “logical” extremities of its use in fiction. Where as real world belief in qi flow suggests that if the direction and path of flow as well as pressure, and release points of this mystical energy can be understood, they can then be used, and/or abused to promote physical wellness as well as sickness, cramps, paralysis, and other internal effects. Hokuto Shinken’s fictional applications force one fighter’s qi into the pressure point(s) of his opponents, causing an immediate overflow. The ultimate effect? Exploding heads. Exploding heads everywhere.

I assume you would understand as much from what I’ve said, but I’ll say it plainly for clarity’s sake: Fist of the Blue Sky, as well as Fist of the North Star, are very bloody, gory, violent series. I don’t expect that to dissuade anyone, but it’s worth saying. The series might be better known for their manly heroics, and modern audiences may not be the type to bat an eye at a little blood and guts but it really isn’t a series I’d expect many parents to be perfectly ok with showing to younger kids. Still not nearly as absurd as some of what you’d find in Riki-Oh.

All in all, for continuing the long running franchise’s reputation for brutal action, manly characters, and general hot-bloodedness, and for adding an extra twist of of genre savvy kung-fu film elements, mobster drama, and of course for Tetsuo Hara’s iconic, rough, gritty art style, I give Fist of the Blue Sky a 5 out of 5 flexes on the muscle scale for manly art, manly story telling, manly characters, manly action, and of course manly character design.

As a sort of honorable mention before wrapping this up, I’d like to point out that I had to really wrestle with the decision of whether or not to include Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure in this article. Ultimately I chose against it -obviously since I’m making this honorable mention instead of an overview- as it would be better saved for a Hirohiko Araki article all its own. That way I can take the time to give the series and its author due credit as more than just a collection of manly men doing manly things.

As a sort of honorable mention before wrapping this up, I’d like to point out that I had to really wrestle with the decision of whether or not to include Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure in this article. Ultimately I chose against it -obviously since I’m making this honorable mention instead of an overview- as it would be better saved for a Hirohiko Araki article all its own. That way I can take the time to give the series and its author due credit as more than just a collection of manly men doing manly things.

I actually really have to apologize, other than just dropping Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure I had initially intended to cover a couple more shows and a game or two (namely the Cho Aniki side-scrolling bullet hell series and the bizarre and flamboyant wiiware title, Muscle March) but at the rate I’m going this article would be a little too long by the time I finished covering a fifth show. Instead I’ve chosen to cut the selection down, omitting all of my video game choices. (But who knows, a certain video game reviewer might be able to cover me with those at some point.) So, while I hate to cut short our time together, it just can’t be helped. I’ll be back following Valentine’s day with a romantic holiday special with an extra special twist of geek added to it. Until then, remember to stay manly, 91.8 fans!

As an important citation: The somewhat bizarre pictures featured above and at the very start of this article are actually part of artist, Yasayuki Sakura’s Power Sculpture: KABUTO PROJECT, which uses the iconic horn of the Allomyrina dichotoma, Japan’s native species of rhinoceros beetle -an iconic emblem of the traditional gambling over insect fights- as a symbol of strength while exploring the power behind the human figure.

[…] with a burning passion. One of these occurred right after he released his manliest review to date, Overcompensating with the Owl in the Rafters, and he proposed a rather… unique game for me to review based on the subject matter. That […]