13 Days of Halloween with The Owl in the Rafters: Day 9

We’ve come quite a ways since this 13 Days of Halloween countdown started, and I’ll admit Day 9 has been giving me a whole lot of trouble. I considered using Satoshi Kon’s psychological thriller Perfect Blue, but I’ve sort of covered that before and I wanted something new.  I considered another personal favorite, the little known Mononoke, but MollyBibbles covered that once already too. I also considered a few other titles that popped into mind but going over them again found them either less impressive than I had remembered, or more inappropriate than I remembered, so in either case got cut from the list. I was actually pretty dead set on using Boogie Pop Phantom for a while but it has been years since I last saw it and didn’t have the patience to rewatch the whole thing. I considered Koji Yamamura’s Franz Kafka A Country Doctor short film for a moment, but that wasn’t so much a horror as it was just bizarre. (Still an absolutely amazing piece though, go watch it!) None of this would have been a problem had I been able to find a copy of GeGeGe no Kitaro to use for day 2, but I couldn’t and so I had to shift everything from day 3 to day 10 down a slot. Finally though, I came to a decision. Day 9’s title is a wonderfully diverse and intriguing 2009 title by Madhouse Studio titled, Aoi Bungaku. (Lit. “Blue Literature“)

I considered another personal favorite, the little known Mononoke, but MollyBibbles covered that once already too. I also considered a few other titles that popped into mind but going over them again found them either less impressive than I had remembered, or more inappropriate than I remembered, so in either case got cut from the list. I was actually pretty dead set on using Boogie Pop Phantom for a while but it has been years since I last saw it and didn’t have the patience to rewatch the whole thing. I considered Koji Yamamura’s Franz Kafka A Country Doctor short film for a moment, but that wasn’t so much a horror as it was just bizarre. (Still an absolutely amazing piece though, go watch it!) None of this would have been a problem had I been able to find a copy of GeGeGe no Kitaro to use for day 2, but I couldn’t and so I had to shift everything from day 3 to day 10 down a slot. Finally though, I came to a decision. Day 9’s title is a wonderfully diverse and intriguing 2009 title by Madhouse Studio titled, Aoi Bungaku. (Lit. “Blue Literature“)

The 12 episode anime series actually covers six different stories, all originally written by four famous Japanese authors, Dazai Osamu, Akutagawa Ryuunosuke, Souseki Natsume, and Sakaguchi Ango. Some are based on novels and some on short stories, covering mysteries, psychological thrillers, and at least one supernatural story. As if the idea of tackling actual respectable literature in the form of anime wasn’t interesting enough, the six stories are split between three character designers of well known anime fame, Obata Takeshi (artist of Death Note, Bakuman, and Hikaru no Go), Konomi Takeshi (Artist and author of Prince of Tennis), and Tite Kubo (Author/artist of Bleach) with each of them designing two of the six stories.

The 12 episode anime series actually covers six different stories, all originally written by four famous Japanese authors, Dazai Osamu, Akutagawa Ryuunosuke, Souseki Natsume, and Sakaguchi Ango. Some are based on novels and some on short stories, covering mysteries, psychological thrillers, and at least one supernatural story. As if the idea of tackling actual respectable literature in the form of anime wasn’t interesting enough, the six stories are split between three character designers of well known anime fame, Obata Takeshi (artist of Death Note, Bakuman, and Hikaru no Go), Konomi Takeshi (Artist and author of Prince of Tennis), and Tite Kubo (Author/artist of Bleach) with each of them designing two of the six stories.

The very first story is Ningen Shikkaku (Lit. “Disqualified from Being Human” aka “No Longer Human“), based on the novel by Dazai Osamu,  which tells the story of a socially distant young man and the distance he methodically places between himself and other people throughout his life. Like a Japanese J.D. Salinger, he used No Longer Human to turn a mirror on post war Japan and show contemporary society through the eyes of an estranged child and the common doubts and fears of a man questioning his own humanity and purpose.

which tells the story of a socially distant young man and the distance he methodically places between himself and other people throughout his life. Like a Japanese J.D. Salinger, he used No Longer Human to turn a mirror on post war Japan and show contemporary society through the eyes of an estranged child and the common doubts and fears of a man questioning his own humanity and purpose.

To be a little clearer about it, the main character, Ouba Youzou, finds that he cannot emotionally connect, sympathize, or empathize with other people because of his methodical and perhaps neurotic way of thinking. He is not noticeably ill however and can easily masquerade as a normal person and does so while yearning for attention and human recognition. When he is forced to make decisions between his own well being and his friends or loved ones, he has no problem with choosing himself over others without a second thought and without any remorse. Although he has no trouble heartlessly abandoning, using, or even killing other people he does eventually find himself bothered by the fact that he isn’t bothered.

Knowing that he can only blend in with society by consciously making the effort to do so, he questions if he is human at all, or if he ever was, or ever can be, and he contemplates what it is that makes a person human and what it is that sets him apart and why, hence the title No Longer Human. Interestingly enough, Dazai was only ten years older than J.D. Salinger and published No Longer Human just three years before Salinger published The Catcher in the Rye so the two wrote very similar novels around the same time and roughly the same age (39 and 32, respectively).

The character designs for No Longer Human were done by Obata Takeshi and directed by Morio Asaka, director of CLAMP’s Chobits, Card Captor Sakura, CLAMP in Wonderland, Galaxy Angel, Gunslinger Girl,FFVII Last Order, and weirdly enough one of the seven credited directors of the U.S. Street Fighter cartoon. Music for the four episodes of No Longer Human was composed by Hideki Taniuchi, the same music artist that did the soundtrack for the Death Note, Kaiji, and Akagi anime.

The art and direction are well done, with a very dark and somewhat faded color scheme that works really well with the 1940s setting. Dazai is of course a well respected international author and No Longer Human is considered his master piece, and is one of the best selling novels in Japan and as such has seen several other adaptations as manga and live action films. Occasionally, it even shows up in the hands of other anime characters as a sign of a contemplative, anti-social, but highly intellectual character: Itoshiki Nozomu of Sayonara Zetsubou Sensei and Ootori Kyouya of Ouran High School Host Club in particular comes to mind. I must confess that the story itself is not so horror oriented, but the direction certainly paints it like one, although the ending turns out to be much more cathartic than terrifying. These first four episodes were also re-edited into a feature length film that premiered on its own the same year the TV series was aired.

Sakura no Mori Mankai no Shita (Lit. “In the Forest Under the Cherries in Full Bloom“) is the next title worth mentioning, if only briefly.  Technically a horror novel by author Sakaguchi Ango, the Aoi Bungaku adaptation is a bizarrely comical and almost musical interpretation of the normally chilling story of a man possessed by a woman’s beauty to commit acts of murder. The character design is by Tite Kubo and the overall mood of the strangely liberal adaptation of the original script is actually very well complimented by his art style. Still, the element of horror is greatly diminished and quite frankly the 1975 live action film of the same name played the story straight and to greater effect. Still, the source material is worth noting, as Sakaguchi was a great writer, although it is arguable that he left more impact on Japan through his essays than his novels.

Technically a horror novel by author Sakaguchi Ango, the Aoi Bungaku adaptation is a bizarrely comical and almost musical interpretation of the normally chilling story of a man possessed by a woman’s beauty to commit acts of murder. The character design is by Tite Kubo and the overall mood of the strangely liberal adaptation of the original script is actually very well complimented by his art style. Still, the element of horror is greatly diminished and quite frankly the 1975 live action film of the same name played the story straight and to greater effect. Still, the source material is worth noting, as Sakaguchi was a great writer, although it is arguable that he left more impact on Japan through his essays than his novels.

The director for this two episode segment was Tatsuro Araki, the man who directed Death Note, Guilty Crown, and High School of the Dead. Soundtrack once again by Taniuchi Hideki, composer of the original Death Note soundtrack. Even putting the quirky direction aside, the original core premise of fearing the entrancing and nearly hypnotic properties of beauty and likening it to lonely cherry blossoms in the woods is a little too abstract for a Western audience, so even with its small helpings of moderately creepy scenes I really can’t speak for it as a horror.

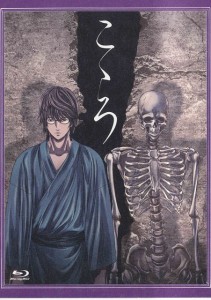

Moving right along, the last piece I really want to touch on is Kokoro (Lit. “[The] Heart“), originally written by Soseki Natsume and featuring more character designs by Obata Takeshi. Kokoro is retold in two different chapters, both following a young man and his friend studying at a university and their romance with the daughter of the owner of the house he is renting his room at. The main character’s friend is a pious monk, and out of friendly generosity, the main character offers to let his friend room with him. The romance becomes a high tension love triangle as the three young adults living under the same room together are forced to hide their true feelings from one another. Who does the young lady of house love? Has there been an affair, or are the two men simply paranoid? Has one of the two friends chosen to steal away the girl from under the nose of his friend? Just who is lying to who and for what reasons? Jealousy, paranoia, and suspicions are pushed to their limits once the mother of the house begins pitting the two young men against one another over her daughter, and the relationship between the two friends only gets worse.

originally written by Soseki Natsume and featuring more character designs by Obata Takeshi. Kokoro is retold in two different chapters, both following a young man and his friend studying at a university and their romance with the daughter of the owner of the house he is renting his room at. The main character’s friend is a pious monk, and out of friendly generosity, the main character offers to let his friend room with him. The romance becomes a high tension love triangle as the three young adults living under the same room together are forced to hide their true feelings from one another. Who does the young lady of house love? Has there been an affair, or are the two men simply paranoid? Has one of the two friends chosen to steal away the girl from under the nose of his friend? Just who is lying to who and for what reasons? Jealousy, paranoia, and suspicions are pushed to their limits once the mother of the house begins pitting the two young men against one another over her daughter, and the relationship between the two friends only gets worse.

Even with practically no violence throughout this particular story, the tension and sense of dread is bone chilling. It becomes clear very soon in the story that the main main character does not trust the people around him, and you get very easily drawn into his own sense of paranoia. There is after all something very distinctly unsettling about distrusting the people you share a home with. Even if it begins with simple suspicion over something frivolous, the inability to address the issue openly can quickly drive the problem out of control. The two episodes each tell the same story, but from the perspectives of different characters. It really is a great little psychological thriller and easily my favorite story in the series.

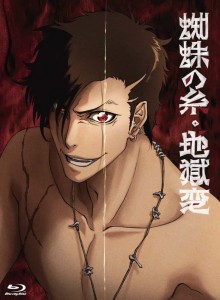

Finally the last two stories start with Kumo no Ito (Lit. “The Spider’s Thread“), the story of a criminal died and gone to hell, but offered a thin thread of salvation as reward for the one good thing he did in life. But his sins outweigh the good he’s done and when he must fight against the rest of the damned to try and escape and . Akutagawa Ryuunosuke’s original short story is a wonderfully typical macabre piece of uniquely Japanese taste, but the particular directorial approach taken in Aoi Bungaku is somehow lacking. Frankly Kubo’s designs and the over all style of the story really weren’t very flattering to the mood of the intended mood of the whole story, and the strangely unique fantasy world, and intentionally trippy direction in the latter half of the episode was really more distracting than attractive. It felt very unnatural and gave off the impression of trying too hard to being bizarre, and ultimately to no real benefit.

the story of a criminal died and gone to hell, but offered a thin thread of salvation as reward for the one good thing he did in life. But his sins outweigh the good he’s done and when he must fight against the rest of the damned to try and escape and . Akutagawa Ryuunosuke’s original short story is a wonderfully typical macabre piece of uniquely Japanese taste, but the particular directorial approach taken in Aoi Bungaku is somehow lacking. Frankly Kubo’s designs and the over all style of the story really weren’t very flattering to the mood of the intended mood of the whole story, and the strangely unique fantasy world, and intentionally trippy direction in the latter half of the episode was really more distracting than attractive. It felt very unnatural and gave off the impression of trying too hard to being bizarre, and ultimately to no real benefit.

The final story, Jigokuhen (Lit. “Hell Screen” aka “Panorama of Hell“) also by Akutagawa Ryuunosuke, was also somewhat sloppily handled. Like with The Spider’s Thread there were simply too many arbitrary artistic liberties for what should have been a fairly simplistic story. The plot was originally straight forward enough: a man is tasked with painting an emperor’s kingdom on the wall of a room, and instead of the beautiful and prosperous kingdom the emperor expects, the man leaves behind a ghastly portrait of the living hell he sees the kingdom as. The direction and art not only simply failed to compliment the story, but actively drew away from the actual subject of the story. Also worth pointing out is that episodes 11 and 12 were run back to back in an hour long special and despite being different stories, director Ishizuka Atsuko for some reason chose to unite the two in the same awkward fantasy world.

That covers five of the six stories, which have various different degrees and elements of horror to them. The one missing story was Hashire, Melos! (Lit. “Hurry, Melos!“) till, putting aside the slightly anticlimactic final episodes, Aoi Bungaku really is a wonderfully well conceived collection of short animated stories with a strong sense of horror and the macabre permeating most of the stories. For whatever reason though, this fantastic little collection has only been released outside of Japan in France so far, although it has been licensed for Chinese distribution. Either way I strongly encourage you to dig up this title if you can and give it a go, paying special attention to the stories featuring Obata Takeshi’s character design.

iStalk? uStalk!