The Owl in the Rafters – Playing Mind Games with Masaaki Yuasa

Welcome back to the Owl in the Rafters! Looking over my recent articles I realized that I hadn’t actually done a proper anthology on any particular figure in the anime/manga industry as of late, so I figure I ought to correct that. This week I’m covering, Masaaki Yuasa, a well known anime director and animator with a long record of work with Studio 4°C, and Madhouse Studios. You may recognize him as the director of the 2010 series, Tatami Galaxy, which won hi the Grand Prize in animation at the 2010 Japan Media Arts Festival, held annually at the National Art Center in Tokyo.

Masaaki Yuasa’s early career in animation include directing the OP and ED of the 1990 anime, Chibi Maruko-chan as well as the 5th and 6th seasons’ OP and the 3rd and 4th seasons’ ED for Crayon Shin-chan. Along with a small selection of Crayon Shin-chan episodes, he also directed episode 10 of the 1994 anime, THE Hakkenden, the original OVA that preceded the 1999 TV series, Shin Hakkenden, both based on the classic Japanese epic novel Nansou Satomi Hakkenden, written by Kyokutei Bakin starting in 1814. The story, literally translated as “Legend of the Eight Dogs” detailed the life and exploits of eight samurai brothers as they fought their way through the Japanese Warring States period. Their adventures drew emphasis to both Samurai and Buddhist virtues, most notably the iconic dog-like trait of loyalty.

Yuasa was also a key staff member as Animation Designer, Character Designer, and Supervising Animator on the short film, Noiseman Sound Insect, which was released in 1997. This short film marked the start of Yuasa’s long standing career with Studio 4°C, a studio notorious for their abstract take on animation and their willingness to really bend the limits of conventional anime. It was working with this studio that really helped open up Yuasa’s range of talent, allowing him to experiment freely with the directorial style that has since made him famous.

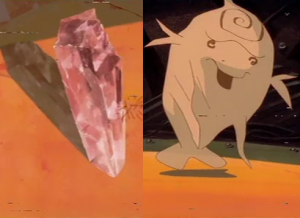

I will be honest I am not perfectly clear on what transpired over the course of the short film, as not everything is shown in an obvious way, and what is shown isn’t always explained. What I could gather was that a mad-scientist created the being known as Noiseman. Using the mad-scientist’s own device, Noiseman separates his creator into two different components: a ghost and a sound crystal. The infant-minded Noiseman then sets his sights on the world and turns the mad-scientist’s device on all mankind, arming minions with his machine and turning people in ghosts to harvest their sound crystals. In the midst of this bizarre monster’s tyranny, a group of children rebel against the Noiseman and his army of strange little henchmen and eventually manage to turn one of the Noiseman’s own contraption against him.

The premise is only slightly convoluted and the plot itself remarkably straight forward, but what really makes this short film remarkable is the superb art direction, and the visual style used. The movie comes across as something like a mix between the Matrix Reloaded and a Doctor Suess book. The film also highlights a distinct lack of exposition, where most of the plot devices are clearly displayed for you, but with no real explanation, leaving you to make sense of things on your own, while reveling in the breathtaking vintage toy-box and candy store like cityscape that whizzes by during the nearly continuous chase scene that makes up most of the fifteen minute short film.

In 1999, Yuasa directed and storyboard’d the pilot episode to Production I.G’s children’s cartoon, Vampiyan Kids. Although he would have nothing to do with the full 26 episode series based off of his pilot in 2001, his pilot remains a notable piece of work in his career. The pilot episode and indeed the series as a whole is much more kid friendly than most of Yuasa’s work, but by the 10 minute mark of the pilot episode, the mood, while still distinctly goofy and child friendly takes on more of Yuasa’s recognizably surreal sense of style.

The story follows a 6th grade boy named Kou and the bizarre antics he finds himself in when he meets with a family of vampires. In the pilot there is little explanation for this, other than mere happenstance. Once inside the vampire’s castle, Kou meets with the father of the family, addressed only as Papa, and his daughter Sue. Kou falls in love at first sight, and Sue is excited to have met a friend, but when Sue asks if Kou can stay for dinner, Papa takes it a bit too literally and spends most of the rest of the episode trying to eat Kou whenever Sue isn’t watching. Midway into the loonytoons-esque run around, a vampire hunter breaks into the castle and attacks Sue and her father. In a fast paced chase scene very much in Yuasa’s iconic style, proportions, dimensions, and perspectives warp around characters in motions, and eventually the entire set begins to literally melt away.

The sense of humor in the pilot episode, while still very distinctly childish has a noticeably demented twist to it when compared to the television series that followed after. Something about the setting, style, and sense of humor have an almost western flare to them. Considering that Yuasa has cited Tex Avery and Ladislaw Starewicz as some of his bigger influences as a visual storyteller, it’s no surprise that there are certain parallels, but it is that subtle charm to it all that really sets Yuasa’s work apart from the run of the mill anime directors over-saturating the market as of the past decade.

Yuasa’s next major step in his career and perhaps the biggest for him, was stepping on board as co-screenplay writer, storyboard artist, and animation producer for J.C.Staff’s award winning short film Cat Soup. The film’s bizarre story, surreal visuals, and unspoken dialogue really showcase how far Yuasa can stretch his wings in terms of his creative abilities alongside director Tatsuo Sato.

The story itself, while not perfectly clear upon first glance, follows a young anthropomorphic cat as he ventures to the far reaches of sanity and reality to retrieve the soul of his older sister. At the film’s start, we see the protagonist playing in a bathtub full of water and submerge himself briefly before getting back out. Meanwhile his older sister lies in bed and witnesses the coming of a psychopomp character based on the Japanese Jizou, an interpretation of the bodhisattva, Ksitigarbha, of buddhist faith.

The young cat presumably comes close to drowning in the tub and the near death experience allows him to also see the Jizou and chase after it as it takes his sister’s soul. He fights over the soul and manages to escape with half of it. Returning home after the incident to find a doctor has just proclaimed his sister dead, he returns half of the soul to her and she awakens from death, but is brain dead. The two venture far off to a bizarre circus where they see a god-like magician perform. One particular act of the circus performance goes awry however and the world apparently floods.

The brother and sister escape of course, and what follows there after only proceeds to get more and more surreal as the two cats delve deeper and deeper into the realm of the dead as they seek the cure to the sister’s vegetable-like state. Meanwhile the god-like magician tinkers with the flow of time, and we watch as a number of deaths undo themselves across time and space. The imagery is truly fascinating and gorgeous, albeit impossibly morbid at times.

Just a year following Cat Soup‘s international success, Yuasa returned to Studio 4°C to his first full fledged directorial role as the director of Mind Game.  The film’s title mostly speaks for itself as the nearly 2 hour long film drags its viewers on a real roller-coaster of a ride following the surreal adventure of a manga artist named Robin Nishi. Robin Nishi is of course also the pen name of author who created the original manga that the film was based off of, although the film is hardly autobiographical. If ever there were an acid trip in the form of an anime, it might just be this.

The film’s title mostly speaks for itself as the nearly 2 hour long film drags its viewers on a real roller-coaster of a ride following the surreal adventure of a manga artist named Robin Nishi. Robin Nishi is of course also the pen name of author who created the original manga that the film was based off of, although the film is hardly autobiographical. If ever there were an acid trip in the form of an anime, it might just be this.

As I already established, the film’s main character is Robin Nishi, an unsuccessful manga artist living in Tokyo, Japan. The story starts when he runs into his old middle school sweetheart, Myon, on a subway train. The narrative here follow’s Nishi’s inner thoughts as all his personal insecurities, and anxieties pile up as he tries to confess the unspoken love he had for her when they were kids. The chances of his hampered but optimistic dreams of romance goes down hill fast after discovering that Myon is already engaged to another man, and a typically strong dependable kind of guy at that.

A yakuza thug and a soccer player with the yakuza’s support barge onto the scene looking for Myon’s father not long after the bittersweet reunion and turn the mood on its head from painfully awkward slice-of-life to a grim, pulp drama. In any case, Nishi is killed in the most embarrassing way, and upon finding himself in the afterlife is forced to watch his own death on loop until he can start to come to terms with it. He doesn’t really accept his death however and after winning a foot race against god, he finds himself alive again just moments before his death, and manages to pull through with a spectacularly goofy turn around before gunning down his would-be assassin escaping with Myon and her sister in tow.

Invigorated and brimming with confidence after his literally death defying escape, Nishi finds himself embracing a hopelessly reckless attitude as he steals the yakuza’s car and quickly finds himself in a hilarious high speed car chase with a dozen or so more yakuza on his tail. The chase scene is riddled with the kind of visual gags that Yuasa has become so well known for, pushing the limits of wacky and ridiculous as we watch the almost cliche action movie style car chase take on loonytoons-esque qualities of the bizarre. The chase comes to an abrupt and bizarre halt however when Nishi ramps his stolen car off a drawbridge and into the mouth of a giant humpback whale. No you didn’t misread that. He ramps the car into a whale.

Once again, the film drastically shifts gears and Nishi and the two girls meet a strange old man who has been living in the belly of the whale for over a decade. The four go about living inside the whale, with Nishi and the girls having to cope with the reality that they may in fact be stuck inside the whale forever and destined to die there. After a series of outrageous and psychedelic vignettes taking place inside the whale, the old man comes to the realization that the whale is slowly dying, and if they are ever to escape they must do so soon, or they will drown to death and die along with the whale.

The film was actually a tremendous flop upon its initial release, but quickly garnered a surprisingly large and particularly strong cult following. Yuasa himself admits to having taken the film as an opportunity to really experiment with both his sensibilities as a director and artist. The art styles change frequently, especially throughout the first segment of the film, and the use of a couple of fast paced montage sequences paint a whole new layer to the characters that goes entirely unspoken in the film otherwise. It really is the kind of film you have to see more than once to really appreciate.

It is worth noting that Masaaki Yuasa was also in charge of key animation for episode 9 of Sunrise Studio’s Samurai Champloo, titled Beatbox Bandits in the English release. The episode focused on Mugen as he raced against time to deliver a package on behalf of the boarder guards holding his companions, Fuu and Jin prisoner.

Moving right along, in 2006, Yuasa found himself working with Madhouse studios on a 13 episode televisions series, entitled Kemonozume. My first instinct is to describe this series as a Romeo and Juliet story, where Romeo is a demon slaying samurai and Juliet is a flesh-eating monster. If you recall the 2003 release of the collection of animated short films released as the Animatrix, then you may recall a segment called Kid’s Story that used a very sketchy but dynamic approach to animation that created a highly exaggerated perspective of objects in motion. While Yuasa had nothing to do with that particular short film, he utilizes a very similar style in Kemonozume.

As I mentioned the male lead character, Momota Toshihiko, is a swordsman trained to hunt and kill man-eating monsters called shokujinki, as well as the heir to the Kifuuken school of swordsmanship. Toshihiko falls in love with a woman named Yuka Kamitsuki, who turns out to be one of the shokujinki. Despite this direct conflict however, the two run away together in the hopes of living out their twisted romance together.

Following the death of the Kifuuken school’s master, Momota Juuzou, and in the absence of his half-brother, Momota Kazuma assumes control of the Kifuuken school, but favors his own mecha creations, the Buster Suits, over the traditional swordsmanship methods of the school’s ruling family. News of the two eloping spreads quickly and the Kifuuken school as well as Yuka’s former shokujinki lover begin sending hitmen after the two.

The basic plot is straight forward enough, but what makes it shine is the art, the animation, and Yuasa’s wonderfully twisted sense of humor. Reprising some of the unique hybrid photo animation used in Mind Game, Yuasa takes a very artistic approach to his direction. Some of the strangely down to earth dialogue that passes between side characters coupled with the fantastically bizarre circumstances and imagery that follow create an unusual kind of comedy.

I suppose I should also point out that apart from being considered a comedy and a romance, Kemonozume is also a horror in the vein of the occult with some heavy gore, and erotica from the logical progression of heavy sexual themes, so there ought to be some fairly strong discretion used before watching this series. Between the unusual art style that may not sit well with everyone at first, and what becomes a fairly raunchy pulp story by the time things get into full swing, the whole thing does tend to seem inaccessible to the typical anime fan. Still, assuming you’re of an appropriate age, don’t let the unusual artistic aspects stop you at the front door, because once you get into it you’ll find this series isn’t just strange for the sake of novelty, but that that story itself is really something different and enjoyable.

In 2008, Yuasa was involved with two different projects; one was his directing his own television series produced by Madhouse studios, and the other was directing one of a series of shorts in the Genius Party anthology by Studio 4°C. The sixth of the seven short films in the first Genius Party collection, titled “Happy Machine”, once again employed the somewhat bizarre art style Yuasa had developed with Mind Game and carried over into Kemonozume.

The 15 minute long film follows an infant trying to escape a eerie, futuristic, automated nursery. The escape begins innocently enough, albeit notably creepy, and then dives straight off the deep end into the kinds of surreal escapades reminiscent of Cat Soup. I won’t spoil the exact ending, but the resolution to the story brings the events of the story full circle in a slightly morbid metaphor for life. Again, I can’t help but liken Yuasa’s sense of imagery to something like that of Dr.Suess, but with a demented streak a mile wide.

Before moving on, I would like to take this chance to encourage you to watch all of Genius Party as each and every short film included in the collection really is a work of art worthy of praise all its own. I don’t want to deviate too far from Masaaki Yuasa’s career in this particular article, but I did want to point that out.

In any case, later that same year, Yuasa directed the award winning 12 episode long television series, Kaiba. (I’m sure you considered it, but no, this has nothing to do with Yu-Gi-Oh) Unlike his previous works Yuasa used a new art style that seems to have  drawn from elements of Osamu Tezuka and Shotaro Ishinomaori’s art styles, 1950s retro future, and 1960s psychedelia. While technically considered to be a romance, and quite obviously a sci-fi, the story really serves as more of an adventure through the bizarre world of the future in which the story takes place first and foremost.

drawn from elements of Osamu Tezuka and Shotaro Ishinomaori’s art styles, 1950s retro future, and 1960s psychedelia. While technically considered to be a romance, and quite obviously a sci-fi, the story really serves as more of an adventure through the bizarre world of the future in which the story takes place first and foremost.

In the future, the human mind can be downloaded and transferred between bodies as regular practice. As a result of the technologies facilitating this breakthrough however there also exists the possibility of illegally stolen or altered bodies. The social structure is very much an Orwellian future, where the rich manipulate the lower classes via their monetary influence and the black-market is rife with both body and memory trade.

As a result of the technologies facilitating this breakthrough however there also exists the possibility of illegally stolen or altered bodies. The social structure is very much an Orwellian future, where the rich manipulate the lower classes via their monetary influence and the black-market is rife with both body and memory trade.

I can’t really describe the plot in detail without spoiling most of the best twists, and considering I’m recommending this more than outright reviewing it, I can’t really afford to do that, but I’ll try to outline the premise: At the start of episode 1, a nameless protagonist awakens without any memory of who  or what he is and in a body that is not his own, and only a blurry picture of a girl found in a locket around his neck, and a strange pattern printed on his stomach as clues to his true identity. Via a series of disjointed clues and hints, the hero explores the wonderfully imaginative world of the future in search of who he is. Of course I also mentioned that this is a love story. The girl in picture in the locket and the hero had fallen in love prior to the events leading to the hero’s amnesia. Again, there really isn’t a whole lot I can say without ruining the mystery of the series, and being lost in the mystery is half the fun. So, as much as I do hate to have to skip over such a fascinating series, we just have to move on for now.

or what he is and in a body that is not his own, and only a blurry picture of a girl found in a locket around his neck, and a strange pattern printed on his stomach as clues to his true identity. Via a series of disjointed clues and hints, the hero explores the wonderfully imaginative world of the future in search of who he is. Of course I also mentioned that this is a love story. The girl in picture in the locket and the hero had fallen in love prior to the events leading to the hero’s amnesia. Again, there really isn’t a whole lot I can say without ruining the mystery of the series, and being lost in the mystery is half the fun. So, as much as I do hate to have to skip over such a fascinating series, we just have to move on for now.

Before we go ahead I should give another note of warning: Tezuka and Ishinomori’s now outdated art styles are often regarded as childish by modern audiences and a similar stigma stays true for Kaiba’s art as well. Do not let that fool you however, as there are some fairly heavy sexual undertones as well as a good deal of casual drug use throughout the series. It may look cutesy and bubbly if you don’t know what you’re looking at, but this is by no means a show suitable for younger audiences.

Skip ahead another two years in Yuasa’s career and we get to a title you all might be more familiar with, his next major television series, Tatami Galaxy which aired just last year in 2010. Many of you who keep up with current releases have probably caught wind of some of the hype surrounding this series, as well as some of the backlash resulting from said hype.

The truth is that the series is very well written, artistically simplistic, and deviates from the look and feel of most common place anime series in the past several years. This has attracted a lot of attention from what some people might call “hipsters” –definitions often differ, but in this case that would be someone who would be willing to watch something just because it’s different, and for the express purpose of saying that they have watched something that is different– but in spite of some of the blindly devout fans over-hyping the series, it is still a legitimate work of art in both visual design and in storytelling, and well worth watching.

The story follows a nameless protagonist who comes to a realization in the second year of his life in university that in chasing a foolishly naive dream of finding love and living a happy, easy life style, and in becoming involved with one particular person, he has wasted the past two years of his life. The protagonist proclaims that if only things had been different two years ago, everything in his life would be different. And so by a twist of divine irony, time rewinds itself to two years in the past, when the protagonist first entered university and joined the club where he met the particular person who ruined his life.

That particular person is a “man with a face of ominous ill portent” named Ozu. A devious prankster, schemer, and all around menace to the people around him, Ozu became the protagonist’s friend and dragged him into his convoluted attempt at terrorizing the general university campus. Of course, the second time around, despite having joined a different club and spending two years of university obsessed with a different inane hobby, all the outcomes were the same, and by the end of the first episode we’re right back at the start with the protagonist insisting if things had just been a little different, it would all be better.

So the first several episodes follow the same formula of the main character joining a club, meeting Ozu, getting into some kind of trouble, and wishing his life were different by the end of the episode. Despite the changes to the main character’s life however, the background events surrounding those two years repeat themselves unaltered, with the main character seeing various events from different perspectives each episode, while certain events that already happened or will happen later roll along without him in the background.

After a number of different lives with different clubs, making the same mistakes and always involving Ozu to some capacity, the main character resolves in one reality that he won’t join a club at all and will simply stay locked up in his room. Obviously he never meets Ozu, and he is unaware of the events that take place over the two years that he has isolated himself from the rest of the university campus, but then comes the twist: he is literally stuck in his room forever.

Leaving through the door, jumping out the window, breaking down the walls, or tearing apart the floor and ceiling, the main character finds an infinite corridor of his one room apartment stretching on into infinity. Eventually this version of the main character realizes that every room is slightly different, and belongs to a version of himself in which he chose some different club, and so by piecing together bits of the previous episodes he comes to realize the big picture of what has been going on over the past two years. Armed with his sudden revelation the main character breaks free of the infinite 4.5 tatami-mat room loop and runs off to rescue his only friend, who he hasn’t technically met in this reality.

The actual events of the story are fairly simplistic, although the order in which they all come across through the plot can be a tad confusing until the final episode. The cast of characters is small, but it makes for a much more intimate relationship between them and the viewer. The characters are remarkably normal, but they grow on you pretty quickly with endearing little faults. All in all it’s an incredibly fun and colorful story that really did earn a good deal of its hype.

So, here we are a year after Tatami Galaxy‘s release, and eagerly awaiting the next big hit from Masaaki Yuasa. Of course, while there are no signs of another big project just yet, Yuasa has also contributed some character design to the French anime-inspired cartoon series Wakfu, and directed the opening sequence to A-1 Pictures Studio’s animated sci-fi epic, Welcome to the Space Show. With everything I’ve laid out here for you today, I hope you’ve gained some interest in Masaaki Yuasa’s work and will not only look into the anime he has been involved with but look forward to work he is involved with in the future as well. It’s been a bit of a lengthy read, but I hope you’ve enjoyed it!

Thanks for another great article. Like many I only know if Masaaki Yuasa from Tatami Galaxy, and its far more understandable regarding the style used after reading about his long history of artistic and perhaps avant-garde work. I definitely appreciate the creativity and efforts to tell a deeper story through the artistry. Now to find some of his past work….

Oh, you’ll enjoy yourself. I’m not a big Kemonozume fan, but his older work is interesting to say the least. Genius Party and Cat Soup are fun in a creepy way 😀

Great job, Tyto, as usual!