The Owl In The Rafters – Place Your Bets On Fukumoto

Welcome to the Owl in the Rafters! In my past two updates I went over the careers of two very talented but sadly under appreciated artists: the first being Komi Naoshi, author and artist of the little known and short lived serial title Double Arts that ran in the weekly Shounen Jump for just 6 months, and the second being Yuusuke Murata, the artist of Eyeshield 21 a sadly overlooked sports title with more general appeal than the subject of American Football would belie. The first of whom I noted was both a strong writer and artist, while the latter could be considered a top notch artist but with a slight handicap in the writing department. To level the scales this week I’ll touch on an author/artist who falls onto the other far end of the balance of artistic and literary talent, a man with superb writing skill but dubious artistic talents, Fukumoto Nobuyuki.

I’ll get this out of the way first and admit that by most conventional artistic standards, Fukumoto might be considered to have poor art skills. This may come as a surprise if not outright shocking to hear said about a professional artist, but the impression comes from a mix of a slightly outdated art style that younger or lesser read audiences tend to be unfamiliar with, and then a genuine problem on Fukumoto’s part with being able to draw in proper proportion and perspective at certain points.

BUT WAIT! Don’t let it throw you off, because if nothing else, the fact that Fukumoto has been a well read author and artist of manga for over 20 years now in spite of his poorly received art style is just a testament to just how unique and fascinating a writing style he has.

In any case, the name is likely unfamiliar to a great many of you, as Fukumoto has no English published titles, nor any dubbed anime series. For whatever bizarre reason however the live action adaptation of one of his manga has apparently been released on DVD in the UK. Go figure. But for all intensive purposes Fukumoto’s work has seen absolute minimal attention outside of Japan. This is somewhat of a shock considering that his work have all sold fairly well since the early 90s. Given the content of most of his stories though, it’s not so absurd to think that his work wouldn’t sell well among the younger target audience of 90s anime in America. What has less explanation however is why the 2007 anime adaptation of the first segment of one of his ongoing series still has yet to see more than a tiny article in a single issue of Newtype USA. I’ll get to all of that in more detail later however. For now I’ll just drop a few facts before starting on a title-by-title breakdown of Fukumoto’s extensive collection of work.

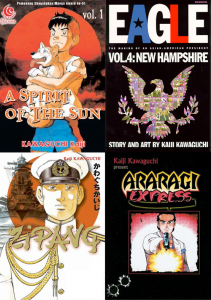

Apart from a total of 2 animated series, one with a second season slated for release later this year, Fukumoto has published 8 different serialized titles -3 of which are still technically considered ongoing- with 3 live action film adaptations of two different titles, Fukumoto has also acted as the writer in 3 different collaborated series with other artists. Of these collaborations, two have been with artist Kawaguchi Kaiji, and one has been with Hara Keiichirou. Perhaps superseding his own cult level of popularity, Fukumoto’s work with artist Kawaguchi Kaiji has produced some of his more widely praised work. Both Seizon ~LifE~ and Confession, appeal to a much broader target audience than Fukumoto’s typical work, and when complimented by Kawaguchi Kaiji’s iconic artwork, they sell on a level nearly on par with Kawaguchi’s own original works.

For those unfamiliar with Kawaguchi Kaiji, he is the famed author, artist, and forerunner behind some of the Seinen demographic’s biggest hit titles, such as Eagle: The Making of an Asian-American President, a political drama (obviously) detailing the fictional life and Presidential Campaign of Japanese-American senator, Kenneth Yamaoka in the 2000 elections and the social and political hurdles he must overcome as a minority candidate; Apocalypse of the Sun, a post-apocalyptic disaster story following one optimistic and determined young boy as he survives the economic downfall and social collapse of Japan following a literally earth shaking cataclysm; and Zipang, a sci-fi military drama detailing the adventures of a modern Japanese SDF destroyer and its crew of trainees when a bizarre storm inexplicably separates them from their crew and they find themselves smack dab in the middle of one of the biggest battles of the Asia-Pacific War during WWII, and a great deal of others. All award winning manga considered masterpieces within both their respective audiences and within their artistic medium as a whole.

The first of two collaborations between Kawaguchi and Fukumoto is titled, Confession, and was released in 1999. The story that Fukumoto presents us with plays with elements of suspense and horror that I can’t help but liken to some of the early work of Alfred Hitchcock, namely Shadow of a Doubt.

When two friends, Asai and Ishikura, ascend the familiar Mt. Owari together as part of a biannual trip with their mountain climbing club the last thing either man expected was for them to be stranded and lost in the middle of a blizzard face to face with a decision that could mean life or death for one of the two men. After Ishikura breaks his leg, he is faced with the seemingly inescapable, cold hand of death up in the mountain storm. As visions of death creep upon him, Ishikura is suddenly overwhelmed by half a decade’s worth of guilt and confesses to his companion, Asai, that five years ago, Ishikura murdered a young woman named Sayuri with his bare hands.

In a sickeningly cruel twist of fate however, the storm lets up just enough to reveal an empty hiking lodge that had been hidden in the blizzard. A rescue team is contacted but can’t make it up to the lodge any sooner than two days with the weather as is. Then the phone line goes dead. And so Asai is faced with a terrifying reality, he is the only man alive who knows Ishikura’s terrible secret, and for the next 48 hours, he is trapped in the lodge with a murderer. Suddenly the situation has changed its tone from dark to darker and Asai is locked into an entirely different battle for survival against not only the mountain, and the murderer Ishikura, but his own slowly escalating paranoia.

In general, Fukumoto’s writing has an incredibly strong focus on inner monologues and following character’s thought processes, but Confession takes that strong point and brings it to a logical extreme, following a chain of implied, assumed, and inferred conclusions to inspire a feeling of genuine paranoia. Stringing together a series of ominous but obscure events and comments, Asai’s inability to truly confirm or deny the implications of Ishikura’s suspicious behavior.

A year later in 2000, the three volume long detective story, Seizon -LifE- was published by the same duo. A man by the name of Takeda is faced with the medical equivalent of a death sentence: in no later than six months before the malignant tumor in his liver metastasizes and kills him. Having lost his wife to liver cancer some years prior, Takeda comes to a disheartening realization when faced with the very afflictions that killed his wife: he never once showed his wife any understanding during her illness.

Wrought with this guilt he finds that he was never truly close to his family, neither his wife, nor his teenage daughter, Sawako, who ran away from home more than 14 years ago. But just as Takeda has resolved to hang himself in an act of suicide, the phone rings. The message left on the answering machine is from the police. Sawako’s body has been found. Suddenly, with only six months left to live, Mr Takeda is told that his daughter’s 14 year old disappearance case has been deemed a homicide, but the statute of limitations on the murder case start on the last day he heard from her, the day she vanished, September 16th, 1984. Suddenly Takeda is faced with a task charged by fate. In six months he will die. In six months his daughter’s murderer will have escaped conviction. And in six months, Mr. Takeda will track down the murder and bring him to justice.

What begins as the premise to a wonderfully dark detective story takes its time building up to the climax, taking the reader through Takeda’s investigation as he retraces his missing daughter’s foot steps and reminisces on what few times of happiness he had with his daughter. It might be hard to understand or truly sympathize with for a younger audience, but from the perspective of a parent or dedicated lover, the terrifying pain Takeda finds in himself will prove spine-chillingly down to earth. The guilt over his negligent parenting continues to build up on him and is what ultimately drives him on his search until finally he finds himself face to face with his daughter’s killer.

At his point the passionate paternal drama takes a back seat to a thrilling series of mindgames as Mr. Takeda and Police Detective Murai must devise a way to corner the killer. In a truly brilliant and colossal bluff, the four chapter long interrogation takes off to a great start and leaves the reader hanging on every twist and turn. Will Takeda see his daughter’s murderer arrested for his crimes, or will he find it in himself to take justice into his own hands?

Now, before I move into the main body of Fukumoto’s work, I’ll say it now that I’m going to go over these in a slightly unusual order. Rather than take my usual route and work through these chronologically I’d like to try and sort these out in a manner that makes the works more accessible to you as a reader. So, to start, we’ll go over Fukumoto’s most recent anime series, Gyakkyou Burai Kaiji.

The 26 long anime series Kaiji covers most of the 13 volume long series, Tobaku Mokushiroku Kaiji the first segment of Fukumoto’s ongoing manga series staring the titular character, Itou Kaiji. When we first are introduced to him, Kaiji is a perfectly average nobody living out a dead end life without any drive or ambition. Kaiji’s story begins when our perfectly average nobody of a hero is visited by a yakuza named Endou who explains that Kaiji is to be held responsible for a loan he cosigned on behalf of a friend. His “friend” however vanished without paying off any of his debt and so the hefty sum of 3,850,000 yen falls on the shoulders of our hero.

Kaiji has no means to pay this debt off however and Endou knows it. Instead Kaiji is given an ultimatum: either he can pay the debt off through honest work (making 900 yen an hour, not taking into account daily expenditure for living expenses) and expect the debt to be paid off by the time he’s in his 30s, or he can board a four hour cruise sponsored by a mysterious black market benefactor and partake in a game that is guaranteed to wipe his debts clean. The catch? Once he’s on the ship he will have to gamble for his life against other debtors. Should he lose his punishment is uncertain, but rumors have it that he could be shipped off to forced labor camps or used as a guinea pig for experimental drugs.

The first season of the Kaiji anime covers a total of 4 different games (arguably 5 as one has two variations) or gambling events hosted by a mysterious and ruthless organization of corporate thugs. Faced with imminent death, Kaiji finds his quick wits awoken by the danger and using an almost detective like sense of deduction he begins fighting his way out of the hole he’s been dropped into by any means necessary.

What makes Kaiji shine as a mind game oriented series is in just how logical Fukumoto really is. Many series that tout supposedly puzzling thoughts and devious schemes suffer from one huge problem, being that at some point or another characters begin making convenient assumptions for the sake of the plot and ignore perfectly valid alternatives to the problem at hand. In other words: plot holes. Fukumoto’s strong point is that in nearly every one of his games, he never proposes that there is any single correct answer, and in fact more often than not a legitimately feasible plan will not only fall apart at some of the most crucial moments, but back fire all together, landing Kaiji in an even worse situation than he started in.

Apart from the puzzles of logic however, Fukumoto has a real knack for drawing out the grimy side of human habits. On more than one occasion characters will launch in truly inspiring, if sometimes unexpected monologues about overcoming defeatist and escapist mentalities, the nature of sincerity, what real drive and determination are, and what it takes to achieve success. Fukumoto’s views and messages can be a tad bit on the cynical side, but this is coming from a man who writes psychological thrillers and mind games for a living, so that should come as no real surprise.

Taking a brief look at the mechanical construction of the series, the art and animation done by Madhouse studios is astonishing. Practically the entire storyboard is original content, drawing little more than the dialogue and a few key angles from Fukumoto’s simplistic panel work. The art style is cleaned up and standardized to solve Fukumoto’s problem with consistent proportions, but the designs are still true to Fukumoto’s unique style.

As I mentioned earlier, the Kaiji anime is in fact just a small portion of Fukumoto’s on going Kaiji series, and a second season was promised at the end of the first, which has only recently been seen to fruition with finalized report surfacing just recently, after 4 years of hiatus on the project. The original manga is broken into 4 different titles; the first is Tobaku Mokushiroku Kaiji, published between 1996 and 199, and serves as the basis of both the anime and the live-action film. Second is Tobaku Hakairoku Kaiji, which ran from 2000 to 2004. Then from ’04 to ’08 ran Tobaku Datenroku Kaiji. And finally the last and still ongoing Kaiji series, Tobaku Datenroku Kaiji ~Kazuya-hen~ which has been running since 2009.

Another big title of Fukumoto’s is Tobaku Haouden ZERO, which ran in Kodansha’s Weekly Shonen Magazine from 2007 to 2009, and is currently on hiatus. Unlike Kaiji and many other of Fukumoto’s work, Zero avoids being about more conventional money-oriented gambling. Instead it plays with games of logic, statistics of chance, and on occasion hard numbers. Ukai Zero is a young boy with a talent for creative problem solving. After saving three boys from suicide, Zero uses them to help him in a risky scheme to steal money from a Yakuza backed bank scandal and return it to the rightful owners. The plan goes almost perfectly, until the three boys working for Zero get caught by the yakuza and forced to sell out their leader.

For all Zero’s craftiness however, his well planned bluffs aren’t enough to save him and his friends once one of the yakuza’s higher ups appears on the scene. But rather than be angry with Zero for his meddling, the yakuza’s superior is impressed, and decides that Zero is a prime target for an unusual scouting operation. The elderly Zaizen Muryou, the wealthiest man in Japan, and a man with a financial vice grip on every major economic, political, and criminal organization in the country is conducting a “Test of Kings” to find a brilliant mind capable and worthy of representing Zaizen in a global competition of the world’s luckiest, smartest, and most skilled gamblers backed by some of the world’s wealthiest figure heads, of which Zaizen is the sole Japanese participant. In other words, the competition will determine who will represent all of Japan in a test of wits on a global scale.

Thus, the young Ukai Zero becomes one of hundreds of participants in a bizarre competition hosted by the Zaizen organization. To determine the most suitable minds in the group assembled, the participants are put through a variety of tests and trials both logical, intuitive, and mathematical. This rigorous series of elaborate and increasingly deadly games is set up like a twisted amusement park, where each challenge has it’s own building and a difficulty level with a measured pay out.

The set up for Zero as I’ve said, is much less gambling oriented than most of Fukumoto’s other works, and while the general set up might technically be more appropriate for a shounen, I do have to admit that it really isn’t shounen material. It is still a fascinating and entertaining read and I can’t help but compare it to the likes of Yu-Gi-Oh if the game in question had been something like Brain Age or Prof. Layton instead of Duel Monsters. That is to say, a game of reasoning and problem solving played with human lives at stake.

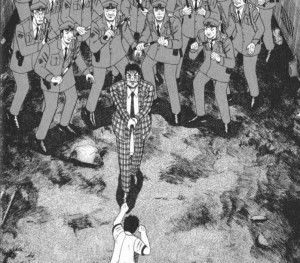

Next up is the oddball in Fukumoto’s litter, Buraiden Gai. While the lynchpin in Fukumoto’s writing style lies undeniably in his mind games, his usual playing field is the realm of betting and gambling. Even in the case of Zero, where the games are still “gambling” even if only by a stretch of the definition, Gai deviates from that path entirely. We are presented with a story about a boy named Gai, who is a wanted delinquent over multiple charges of brutal assault. He is finally apprehended when he is targeted by a wealthy family looking for a fall man to pin the blame on for the financially motivated murder of the family head. As a minor, Gai can’t actually be incarcerated in a prison, so instead he is shipped off to a shady juvenile detention facility run by a cruel and sadistic warden.

Gai isn’t the type to have his will power crushed under heel however, and when he sees the opportunity to escape he takes it. There is but one snag in his escape, not only does he have no idea where the facility is located, but hidden somewhere is the evidence of his innocence in the murder case. In the isolated detention center, Gai must find the evidence he needs and then a way to escape under the noses of dozens of armed guards. If he is caught, he might very well be tortured to death by the mad warden.

Buraiden Gai compensates for Fukumoto’s usual lack of physical action with an almost pulpfiction kind of over the top action and sense of style that jumps from hand-to-hand brawling, to bizarre methods of torture, to suspenseful chase and escape scenes. Never minding some of the obvious nazi-esque visual themes in the prison warden and his guards, the story itself really does feel like something you’d read in an old 10-cent novel in the 1950s. The over all message in the series is also fairly uplifting, and interestingly opposite to the morals of Kaiji.

Ok, now before I go any further I’m going to have to explain a few things about the game Mahjong. Mahjong is a popular game throughout most of asia that is, in Western standards, comparable to poker in terms of popularity and Gin Rummy in terms of gameplay. I could launch into a full article all its own on the rules of mahjong and its prevalence in anime and manga, but I’ll spare you the grief and try to give you only the bare essentials.

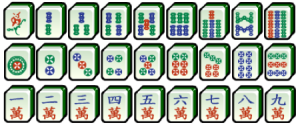

First things first, I’ll just clarify that mahjong is absolutely nothing like the mahjong-solitaire game that you tend to see on the internet, or in cheap computer game bundles, or on small western developed DS games. Mahjong is originally a Chinese game that made its way throughout the Asian continent via China’s strong economic influence over the region as both a popular game and a lucrative form of gambling. Japanese Riichi Mahjong is just one of many variations of traditional Hong Kong style mahjong with its own particular rules. Japanese Mahjong is typically played with a set of 136 tiles consisting of two different types: the first are Simple tiles, and the second are Honour tiles, both of which can be further divided into suits.

The Simple suits are Bamboo (Sou), Coins (Pin), and Written Characters (Man). Each suit consists of 4 sets of numbered tiles from 1 to 9, for a total of 36 tiles per suit, and 108 Simples total.

The Honour suits are Wind (Kaze) and Dragon (Sangen). The Kaze tiles consist of 4 of each of the 4 directions, East (Ton), South (Nan), West (Sha) and North (Pei), and the Dragon tiles consists of 4 of each of three colors, Red (Chun), Green (Hatsu), and White (Haku) for a totals of 16 Wind, 12 Dragon, and all together 28 Honours.

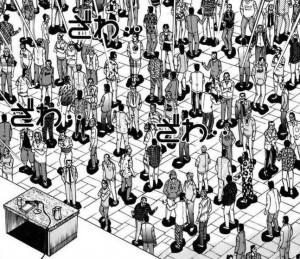

Now, the game is played between 4 players each being dealt a hand of 13 tiles save the dealer who is first dealt 14. The dealer discards one of his 14 tiles to start the game and then the game continues in a pattern of each player drawing and then discarding tiles in sequence.

The goal of the game is to complete a winning hand. A winning hand’s basic requirements are a single pair of the same tile and any assortment of triplets, quadruplets, or a sequence of three ordinals. i.e. 1-2-3, 4-5-6, or 7-8-9, etc…

There are two basic ways a player can come into possession of a tile, either by drawing from the Wall of tiles or stealing another player’s discard in one of three ways. First: If a player discards a tile that another can use to complete a triplet or quadruplet, another player may call Pon and steal that recently discarded title in place of drawing a tile from the Wall. Second: if the above situation occurs with a quad instead of a triplet the player calls Kan to steal the tile. The third steal can only be made from discards made by the player sitting left of the one intending to steal: In other words, if the player who typically plays right before you discards a tile that completes a sequence of 3, you may call Cho and steal that tile.

If no steals are made after a discard the next player simply draws from the Wall.

When a player discards, they do so into their personal discard pile called a “Pond”. A common strategy both in real mahjong and in mahjong manga is to watch an opponent’s pond in order to determine what tiles they had, don’t need, and were hanging on to by watching what is kept, what discarded and when during the game. By watching these moves carefully a player can sometimes determine what kind of hand another player is trying to form, and thus what tiles he/she should avoid discarding.

And finally, there is the unique Japanese rule concerning the declare of Riichi. When a player’s hand is only one tile off from being a winning hand, the player may place a 1000 point bet by declaring Riichi. Once declared, the player can no longer alter his hand, leaving him with only the option to wait for his winning tile to appear either in discard or from the Wall when he draws. The pay off is that should the player get his winning tile before another player declares a winning hand, his hand is worth more.

Two other small notes to make are then when a winning hand is made from a stolen tile, the winning call is Ron. When a winning hand is made from a Wall drawn tile, the winning call is Tsumo.

That is all I will be going over for the purposes of this article. For a more in depth, step-by-step look at how to play Mahjong I can point you along to this site among many others floating around the net that can help. I do hope you will be interested in learning more about this game, as it is not hard to pick up in the functional sense, although there are many finer details -such as the dealing process, seating arrangements, specialty hands, and the entire subject of scoring- that I have omitted for the sake of saving time and space. For the most part, understanding these basic rules are really all you need to at least keep up with Fukumoto’s work.

The reason I stopped to give you that little briefing is that a good bulk of Fukumoto’s stories have revolved around Mahjong. The biggest of them has been Akagi, which follows the life of Akagi Shigeru, a genius gambler with a natural draw toward dangerous gambles as he begins his legendary sweep of the gambling underworld at the age of 13. The series has had 2 live action adaptations and an animated series. Initially Akagi was actually a character in a different Mahjong series of Fukumoto’s, his very first series, which started in 1989 and finished it’s 18 volume long publication in 2002, TEN – Tenna Toori no Kaidanji.

Ten, as I’ll be shortening it to from here on out, is a story follow the titular main character, a contract gambler paid to win money off of dangerous high-stakes players, and Hiroyuki, a young up and coming mahjong player intent on paying his way through college with his gambling money. The main character, Ten, is something of a wild card, a large man covered in scars, but with a goofy, light-hearted, and gentle personality. More importantly his mahjong playing is equally deceptive and unpredictable.

While Hiroyuki quickly finds himself sucked into the career of a representative mahjong player for a local yakuza, Ten tries to teach him the harshness of the gambling world, where luck and skill aren’t enough to trust your fate to and even the most simplistic and underhanded tactics have to be used to ensure victory, even if it means being accused of cheating and beaten afterwords. it is only midway into the series that Akagi appears in his later years as a legendary mahjong player and a friend of Ten’s who serves as another mentor figure in Hiroyuki’s growth as a gambler.

Following Ten there were two spin off series: The more recent has been the 2009 publication called HERO: Gyakkyou no Touhai of which I must confess I know nothing about, save that it is drawn by a man named Maeda Jirou and takes place after Akagi’s death in Ten. The other spin off, and the one that I can actually speak of is Akagi ~The Genius who Descended into Darkness~, which served as a prequel to Ten, detailing the beginning of Akagi’s legendary mahjong career.

The story begins when Akagi is just 13 years old, a strange boy with a cold ruthless demeanor living in Japan just after the end of the war. After playing a game of chicken with a gang of delinquents that left his opponent hospitalized and potentially crippled for life, Akagi is on the run from the police when he ducks into a mahjong parlor for shelter. Using his eerie, quickwitted nature, he helps a desperate man engaged in a game against a yakuza group in a game of mahjong in return for securing an alibi to feed the police. Despite never having played mahjong before in his life, the young Akagi quickly picks up on reading his opponent’s intentions which lends him enough insight to pull through a miraculous win. However, Akagi’s methods of “gambling” are anything but luck, as his ability to dig deep into his opponents’ psychological habits is what allows him to pry victory out from under them when they least expect it. Following his bizarre debut in the world of mahjong, the mysterious 13 year old vanishes for a number of years, until rumors of his talents prompts a yakuza to search for him in the hopes of recruiting him as an unbeatable rep player.

At the end of the Akagi anime, and in one of the bigger events in the manga, Akagi plays an unusual game of mahjong against a villainous millionaire, a man reputed to have built his fortune on the very foundations of Imperial Japan. Having fallen from his place of power and wealth along with the nation following the war, the now psychotic Washizu Iwao has been challenging mahjong players to high stakes gambles with their lives on the line. For whatever reasons this villain was particularly popular and became the subject of a series of spin-offs of Akagi. Yes, that’s right, the spin-off series was popular enough to get its own spin-off series. The shorter of these was a one-shot, surprisingly enough done by CLAMP of all people, the world famous all-female group known for defining the image of popular shoujou manga between the 80s and 00s. The more detailed title however, is the ongoing spin-off by Hara Keichiirou, entitled Washizu: The Demon of Mahjong, details the history of the character Washizu and his rise to power during the waning days of Imperial Japan.

All of Fukumoto’s mahjong titles have been big hits in Japan and Fukumoto himself could be credited as one of the pioneers of the mahjong and gambling niches in manga that became popular in the late 80s during Japan’s economy bubble. The game and concept may be oddly foreign to Westerners but the game and the historical context of its popularity in Japan has enough depth to it to make it a strong stand alone sub-genre of sports manga.

Unfortunately, I’m going to end this article a tad bit short. While I’ve covered Fukumoto’s more mainstream accessible titles and tried to give you a brief introduction to Fukumoto’s mahjong related works and the genre they belong to, there are still a good number of titles that didn’t fit into either category and that I’ve left untouched. Namely Gin to Kin, aka Silver and Gold, and The Legend of A Strongest Man, Kurosawa. Fukumoto’s influence on the seinen demographic and the psychological thriller genre has been mostly unaddressed in the US, so I hope this has provided a brief glimpse in to some of what this remarkable author has been behind and has piqued your interest enough to dig up one or two of his series to have a look for yourself.

Fukumoto is one of my favourite mangaka, and as such, thank you for sharing his greatness with the world!

I’ve been excited to do an article on his stuff for awhile now. he needs more exposure outside of Japan. Are you as psyched as I am for Kaiji season 2?

This is good stuff! I loved Akagi and thanks to this I can check out even more awesome works like Tobaku Haouden ZERO (which is awesome by the way!).