Tempest’s Downpour – Anime In-Jokes 11: Death

Some anime are quite merciless in killing off favorite characters. But it’s rare to deeply explore themes of death in anime: funerals, grave-sites and even the relevance of death deities. What we do see is absolutely bogging to Western audiences.

First, let me throw some statistics at you. Unlike in the West, nearly 99% of Japanese bodies are cremated and the urns containing the ashes are buried, though scattering the ashes has become popular as of late. Cremation is favored because Japan is literally running out of room – a theme explored in the series Tokyo Babylon where Hokuto and Seishiro discussed how grave-site land was being repossessed by the government.

91% of Japanese funerals are conducted as Buddhist ceremonies. These private ceremonies are held only for the family and include washing the corpse, wetting the lips of the corpse and dressing the corpse in a kimono crossed right-over-left (the opposite of how the living wear their kimonos). For a better view on the rituals involved in Japanese funerals, I recommend the movie Departures. Japanese funerals are considered very private things that are never discussed openly, so apparently the director was worried that this award-winning film would have terrible reception.

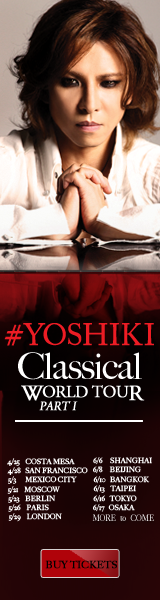

Most homes (especially those farther from big cities) have a Buddhist altar called a butsudan. Butsudans are decorated with incense, candles, food offerings and can have gold inlaid. Typically in anime a moment happens where a character visiting the house of another sees a photograph of a dead relative sitting on the butsudan. The Japanese like to honor their dead, but if a photograph remains on the altar long after a relative’s death, I think that’s supposed to signify how the family has not moved on.

Two angles of the butsudan in the Fujioka family: Haruhi’s mom’s photograph remains in the altar years after her death.

In a very special episode of Fruits Basket Tohru, Kyo, Yuki, Uo and Hana all go to visit the grave of Tohru’s mom. The grave is a huge white monument with a shelf on it. They see that an offering of food has been left on a shelf of the monument.

Typical fare for the dead is a bowl of rice with chopsticks sticking straight down into the grain. That is how east Asian cultures offer food to the deceased and why it’s impolite to rest your chopsticks in the bowl in Asian restaurants. Sometimes family leave offerings of the deceased’s favorite food instead.

Chopstick etiquette for the dead.

The Fruits Basket entourage carries on by having a picnic at the grave site, which is a little unusual even by Japanese standards. What’s important to note is that the Japanese culture has a deep tradition in keeping a strong connection with dead relatives.

For example, the Obon Festival is celebrated every year on three separate occasions. This holiday exists to honor dead relatives and ancestors with the belief that the dead come to visit the living family through the butsudan. This holiday also acts as a family reunion for the living, who come to clean and polish the graves and leave food offerings.

Two angles of the Honda family monument.

Of course, some ancestors aren’t given proper funerals rites or have such a strong emotion attached to their deaths that they cannot rest in peace. If Yurei (Japanese ghosts) are fortunate, living people will give them proper rites or resolve their emotional problems so they may be put to rest. Others wander the world for eternity. In Japanese theater, ghosts are always shown wearing white kimonos.

Some ghosts come back for revenge like Onryo, a spirit that comes back from purgatory, or Goryo, a high-class ghost. Some died in duty like Samurai ghosts or the Funayurei who died at sea. Zashiki-warashi are child-ghosts who just want to cause some mischief, while others just want to be loved: the Ubume died in childbirth so she returns to care for children while the Seductress Ghost does… exactly what it sounds like. The two specifically Buddhist-related ghosts are Gaki and Jikininki.

I didn’t find any proof to back up the following claim, but I remember reading it in a book once, so bear with me. Ghosts in Japanese media are represented by Honou, or spirit flames, which isn’t the least bit like the Western interpretation. They’re visible in anime quite often as bluish or whitish little balls of fire that float. Typically more than one gather to an area and sometimes they are sentient. Characters with fire-themed attacks in anime typically have something related to Honou: Hikaru from Magic Knight Rayearth and Sailor Mars from Pretty Senshi Sailor Moon are among them.

Western audiences immediately recognize this phantom as a ghost, while this creature could be intended with a completely different meaning.

Unlike ghosts, Shinigami are death gods, sort of the equivalent of the Grim Reaper. Surprisingly, this myth does not originate from Shinto lore and may date back as late as the 17th century from European influences. Nonetheless, Shinigami have been popular in Japanese media of late from DeathNOTE to Bleach.

There are two death-centric deities that are actually from Japanese lore: Izanami-no-mikoto (Shintoism) and Enma (Buddhism), the former making central appearances in Shin Megami Tensei games and the latter making appearances in Yu Yu Hakusho. Izanami is the goddess of creation and death, while Enma judges rewards and punishments of the dead in Jigoku – the Japanese afterlife.

Maybe now those weird Obon scenes and hauntings will finally start to make sense. Try not to get too depressed the next time your favorite character is seen wearing a white kimono and remember good chopstick rules in restaurants or else you’re essentially threatening the waiter.

Very interesting, particularly the shinigami and learning what the botsudan is~ Any idea why they wet the lips of the dead?

American cemeteries feel so lacking next to many older cultures, don’t they? I’m thinking of Italian cemeteries, at least where my family descends from-space is limited by the hard mountain rock, so caskets are slid into slots on artificial walls or put in a nice outer container on the ground in rows for a while. Some have a family mausoleum, and there’s a section in the cemetery for deceased children. As time passes, the caskets are removed to a less visual, more practical storage area to make room for the more recently deceased. I think the bodies are cremated sometimes, my mother always commented on how much more practical that is since ground burial eventually takes up so much space, and hacking slots into rock walls takes so much effort.

Do the Japanese tend to put a photograph of the deceased on the monument as well as the botsudan (which was great to learn about just now, btw)? Italians usually have a photo embedded in the tombstone, which I so wish American cemeteries would do-especially if it’s a youth shot as well as one in old age, to really put a face to the name ;_;

Oh, and one thing I feel should have been mentioned in the article-deceased names are in black ink, but I’m pretty sure it’s common to have a space next to the person for their spouse, who’s name is listed in red ink. In Italy, a yet-undeceased spouse has a slot reserved that’s either blank or only lists their name and date of birth. It was a little eerie seeing the slots for two of my long-lived relatives next to their spouses, who died years and years ago, as I thought about how surprised the still living spouses may be that they’re still living so many years later.

There-I owe you comments in so many other articles too but here’s a super long one to make up a little for forgetting to read!

Heeee, man I love when you read my articles because you always have something so intelligent to say. As far as I know, the Japanese do not put a picture of the dead on the monument, since the dead visit the butsudan and not the gravesite.

If a married person dies, it was once common to put the name of the living spouse on the tombstone in red ink — correct. The reason is that it was cheaper to carve two names at the same time rather than spend the money for one and then the other. But since marriages don’t last forever anymore, the practice is falling out of popularity.

<3 Thanks, and I really do want to comment on more of your articles…an article a day maybe, then I'll finally get that done.

Carved, right, the names are carved due to the cost. It makes sense for the practice to be falling out of use, or at least waiting until, say, the couple's reached their 60's or 70's before deciding to do the red ink thing. It also sounds like photographs are indeed used for the botsudan, not the family memorial.

Another thing I thought of related to the article: the association of four with death, thus enemy groups being likely to appear in groups of four. Ever-wonderful TV Tropes has the "Four is Death" trope, with its amusing elevator floors example as well as information on similar unlucky numbers from other cultures and religions. There's even more number and chopstick superstitions, amongst other things, listed on the Japanese Superstitions page on Wikipedia. Ahh, folk culture is so fascinating!

Japanese funeral culture, and belief in the afterlife is very interesting. We actually were talking about this in Japanese class the other day when we were talking about the differences between buddhist temples (o)tora and jinjya although of course he was no talking about the fact that the distinction is only done by the west. He mostly talked about the importance of Shinto shrines are for life, and how buddhist ceremony and temples are usually, but not all together representations of death. Considering the Japanese have tons of names for Shinto temples.

Great post. Watching anime one can learn a bit about the Japanese culture. The alter to deceased family seems present in so many shows. But I still don’t quite understand all the nuances around it. I did know about it being impolite to rest the hashi in the food I didn’t know it was related to an offering for the dead. That would explain it.