13 Days of Halloween with The Owl in the Rafters: Day 11

Today I’m going over a touchy title, often cited as a masterpiece of Japanese Horror,  and at the same time notorious for disappointing viewers who go in with the wrong expectations: Audition. Although I actually question my ability to reach that proper balance of favorable impression without stepping into over-hype territory, I will try my damnedest to get it somewhere around that ballpark.

and at the same time notorious for disappointing viewers who go in with the wrong expectations: Audition. Although I actually question my ability to reach that proper balance of favorable impression without stepping into over-hype territory, I will try my damnedest to get it somewhere around that ballpark.

I will caution you right now that this movie is not by any means appropriate for the feint of heart, or weak of stomach. The film not only deals with heavy themes of sex and torture, but makes the bulk of the torture happen in a single 5 minute long scene. Those five minutes will seem excruciatingly long for just about anyone, and for the squeamish the very audio carried from the obvious implications up until that scene could be enough to bother people deeply.

Audition is a tricky title to break down, as the film can be oppressively slow, and for some this will mean oppressively boring, in the beginning of the film and only gets to the horror after transitioning through several stages of story telling. The idea is to work from drama to comedy, to mystery, to horror: the drama draws you into the characters, the comedy makes you comfortable, the mystery gets a hold of your curiosity, and then the horror hits you full force in the heart, mind, and stomach as you watch the characters you love abused, the comfortable atmosphere and sense of security and privacy shattered, and the torture is really only there as the final punctuation on the discomfort rather than the statement of horror itself. To try and work this as best I can I’m just going to give you a break down, almost scene for scene, of the major events of the first half of the film, while taking the time to point out and explain the basic elements of the story. Ideally this will help you draw some meaning from and maintain interest in the somewhat lengthy build up, so you won’t be as tempted to drop the film before the horror really kicks in. For the sake of space I’ll try to avoid diving into the cinematography, as that could easily double the size of this review. (You may be thinking that I don’t usually worry about cinematography when doing reviews anyhow, but in the case of anime, cinematography is so poorly used and so rarely given any consideration beyond “Rule of Cool” that it just isn’t worth talking about. Sadly the same can be said for most low budget Japanese films TV dramas. In well done film however, most every scene and every transition in conjunction with the script is loaded with meaning and intention.)

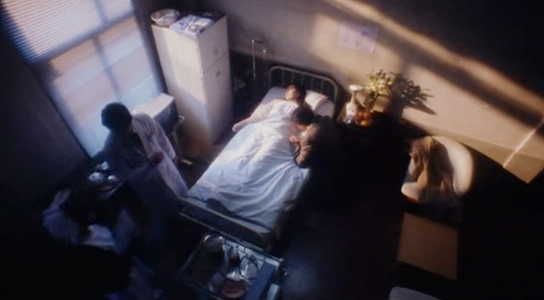

When the film starts, we see Aoyama Shigeharu, the quintessential Japanese businessman, lose his wife to some indistinct illness(probably cancer) in the prologue to the film. At this phase you don’t quite grasp the feelings of the character as you have no reason to sympathize with Aoyama just yet, but it comes into play later. After the wife flatlines, Aoyama’s young son walks into the hospital room with a get-well-gift for his mother, obviously with the expectation that she’s still alive. Aoyama manages to regain his composure, and upon looking at his son accepts that he has an obligation to be strong enough to raise his son by himself now that his wife is gone. This opening scene manages to display the roots of Aoyama’s character entirely as the feelings of personal loss, remorse, and then obligation will prove to be his defining characteristics throughout the film. The title then quietly sneaks into frame as Aoyama and his son walk home from the hospital together.

Fast forward seven years into the future and Aoyama and his now teenage son are out fishing together. There is a distinct closeness between the two and then begins the first half of a particularly meaningful exchange using fishing as a metaphor for romance. Cutting from the fishing scene to the two men eating their catch for dinner, Aoyama comments that his son never brings any friends over for dinner, and asks if everything is alright. As a kind of tit-for-tat for his father implying that he’s a lonely person, the son brings up that his father isn’t a young man anymore and should consider remarrying while he still can. The son also brings up a kind of anecdotal factoid about sea-bream changing sex during their life cycle, which leads to Aoyama making the comment “I don’t know much about ovaries.” Of course this refers to the fish’s anatomy, but the statement about his character is obvious and comes into play again later.

Changing scenes again, at some indistinct time in the very near future, Aoyama is watching an employee go over some unedited film of a “concert”, although it looks to be more like a rave. The editor cynically comments that the concert goers are like cultists, gather together in some inane worship for the sense of belonging and company rather than the music. He says that all of Japan has become helplessly and desperately lonely. Aoyama asks if that goes for him as well, and the editor lightheartedly returns the question, “Aren’t you?” This is of little consequence by itself, but in it we can begin to see how the sense of loneliness is surfacing in Aoyama’s life. Every time this idea of loneliness comes up, Aoyama is reminded of the death of his wife, and in some small way relives a part of that distant pain.

As Aoyama leaves his office for the day, we are briefly introduced to Aoyama’s nameless secretary, and given a glimpse of their awkward relationship. Aoyama seems to actively avoid prolonged discussion with her and when she stops him for a moment by saying she’s getting married soon, it feels like she is trying to solicit some kind of reaction from him, any kind of reaction really. Aoyama brushes her off without saying much and maintains his distance. The implication is that they had some kind of romantic relationship in the past, which Aoyama now refuses to carry on, or even acknowledge. This addresses the more literal idea behind the comment about the sea-bream that the son mentioned over dinner: that Aoyama just doesn’t seem to understand women.

At the end of the day we see Aoyama at a bar with a friend, Yoshikawa, a business man in the film industry. Yoshikawa laments that his business isn’t doing well, and through the course of the conversation likens the wait between money invested in a film and its pay out to torture, or a survival game. He says there may be some profit at the end of it all, but the wait through uncertainty until knowing the outcome is what is unbearable. This comment alone mirrors and ultimately sums up the heart of the film and most of its key moments, most obviously the big torture scene. In any case, the conversation ends humorously when Aoyama points out that Yoshikawa has given the same spiel before, which Yoshikawa shrugs off. The two have their attention drawn to the next room over in the bar, where a group of young women cry out in laughter, and suddenly we realize that Aoyama and Yoshikawa are the only people in the main section of the bar, again highlighting the loneliness surrounding Aoyama.

Aoyama takes the opportunity to confide in Yoshikawa over his consideration of remarrying, and that he doesn’t know how to go about finding another wife. Yoshikawa inquires as to Aoyama’s plans and interests and devises a plan for his friend: the two men will stage an audition for a film, and under the guise of looking for a perfect leading actress, search for Aoyama’s perfect bride. Yoshikawa’s logic is thus: a leading actress will be too attractive, talented, and self-sufficient to be looking for a husband at her age. So the plan is to audition the women for the film and actually produce if all goes well, but have Aoyama pick through the girls who don’t make the cut to find his future wife.

By the next major scene, Aoyama is thumbing through some of the resumes and attached photos of the auditioning actresses, and by chance, at the very bottom, finds a picture of a certain girl, Yamazaki Asami, that catches his attention. Also during the process his son announces that he’s brought his girlfriend home for dinner. Aoyama tells his son he won’t be eating with them and to give the girlfriend his dinner. In some ways this could be the final bit of pressure that pushes Aoyama toward committing himself to the idea that he must find a new bride.

Also worth pointing out is that as he is going over the applications at his desk, Aoyama is offput by the stare of his wife’s photograph and turns it to face away from him. This is notable because he does not actually put the photo face down, but simply away, showing that he hasn’t really gotten over her death. This is cemented when he reads the written portion of Asami’s resume in which she brings up how she used to practice ballet, but broke her hips, and how giving up dance was like coming to terms with death for her: as in she envisioned her life as something driven by dance, and by being unable to dance, her entire idea of what her life could/would ceased to be, her future self, killed. Aoyama is reminded of his wife, while she was alive but still hospitalized, and presumably likens that coming to terms with death with his wife’s own struggle against her terminal illness and having to watch her own future die.

At this point the films plays out roughly 30 interviews with various women through a cynically comical montage of the 30 actresses answering arbitrary and often awkward questions, and displaying various misc. talents, and showing off their bodies to various degrees, until finally Asami appears. Aoyama’s attention is still hooked from first seeing her resume and he becomes infatuated with her. He listens intently to her speak as Yamazaki runs her through the interview, until he begins to question Asami about ballet and what she had written in her resume about her sense of having confronted death. Yamazaki can tell Aoyama is interested and sits back to let him get his questions out.

Yamazaki sees right through Aoyama’s little infatuation but insists that something is off putting about the girl. Naturally Aoyama shrugs the premonition off and insists that she’s the one. When he gets home that evening, he and his son discuss the girl the son brought over, which the son confesses he doesn’t have much lasting interest in. This is of course a reference to how you can’t judge a book by its cover, or how you can’t expect to know a person from their first impression: the fatal flaw in Aoyama’s current thinking that facilitates the entire point of the film. This also goes to note that while the son is taking things in stride, Aoyama may be rushing ahead without thinking clearly first.

To further cement this indication that Aoyama’s little love-at-first-sight syndrome is doomed to fail, Yamazaki calls later that night and tells Aoyama that after poking around a little, part of Asami’s story during the interview is a little fishy, and her facts don’t add up right. By this point Aoyama has already taken things into his own hands and invites Asami to dinner with him against all of Yamazaki’s warnings. He does try to casually bring up some of the discrepancies in her story with her over dinner, but she manages to awkwardly sidestep them and Aoyama makes no effort to press the matter.

Again, Yamazaki makes an appearance to caution Aoyama against pursuing Asami too hastily, and points out that after continuting to investigate her, he has found no corroborating information, and stranger yet has found not a single contact of hers to even begin confirming any of her information. Again, Aoyama ignores his friend’s warnings, much to Yamazaki’s distress, but Yamazaki’s specific request that Aoyama not call Asami again sticks with him… at least at first.

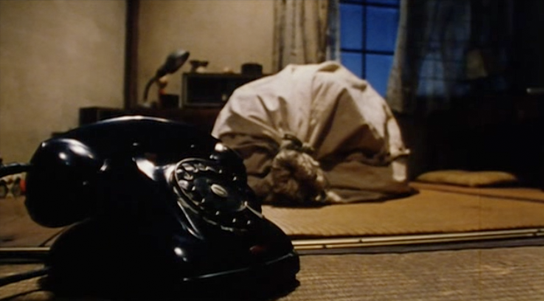

We then get the famous scene of Aoyama and Asami in their respective homes that night, waiting in hopes of the other one calling: Aoyama lays awake in his futon with the lights off, and Asami sits on the floor of a tatami mat room with her lights on, and an ominous looking sack in the back of the room. We eventually get another look at the room when Aoyama considers calling Asami at the end of the next day and decides against it, if only briefly. With our third look at the room, we hear a chilling phone ring pierce the silent room and the bloody sack in the back of the room jumps.

I think by now I’ve given you a basic idea of the mood the film is setting, and the sense of uncertainty that it tries to perpetuate. As a good horror film should, it plays with the boundaries of what the audience and characters can see in contrast with one another. You yourself are entirely aware that Asami is likely a murderer and fully aware of Aoyama’s seemingly fatal shortsightedness, but it is not any sort of relation to his own plot driven ignorance that drives the fear into the viewer, it is the unpredictable nature of Asami’s character. The real suspense comes from the fact that you do share some uncertainty with Aoyama in that you still don’t know Asami’s background, and even if your perspectives are different, you both ultimately want to know the truth behind this mysterious and dangerous woman.

Watching Aoyama after knowing his past doesn’t make you empathize with him, as some critics try to protest, but the fact that you can still sympathize with him on some level, even in spite of the usual contempt for short sighted horror protagonists. As you both come to learn of Asami’s background, and as you watch Aoyama’s horrified reactions to the truth as it is uncovered, it does start to draw you into his mindset, if only barely. Combine this with some genuinely well employed dream sequences that serve to question how much of the film is real and how much is a figment of Aoyama’s paranoia and anxiety and the whole film comes to a genuinely heart racing climax.

Again, there are very heavy sexual themes to this film and in fact not long after where my synopsis left off Aoyama takes Asami on a weekend vacation in order to propose to her, and while not explicitly graphic, the sexual content probably merits an R rating. Similarly the gore element is actually not as heavy as other films using the same gimmick. It’s not that the torture scene is done in any kind of eloquent or tasteful way (not that I’m even sure there is a way to tackle the subject in such a manner) but just like the sex scenes you never see any insertion, it’s all just very heavily and very obviously implied. At the bottom line all the worst parts are left to your imagination and you don’t actually see anything, and really that’s what gives it such power. You know where things are going, and there really is no need to make elaborate prosthetics or props just to give you one cheap squick scare when you can achieve just as much, if not more, without showing the audience anything at all.

What lends to the film’s real psychological impact is the idea of retribution, both for his wife and for women in general, as the the film does tend to highlight the very common chauvinistic trends in Japanese culture to some obvious degrees of exaggeration. The actual audition montage is actually the most notable scene in this sense because the comedic element really does downplay the nature of the audition, which by most standards would be seen as sexual harassment or downright extortion. Historically the Japanese have never had very much equality between sexes and at the same time many famous figures of Japanese history and common figures of mythology and folk lore involve the majesty and grace of powerful women as well as the vengeful anger and spite of a woman wronged. Without going as far as to invoke any actual supernatural elements to the story the film manages to give off the distinct impression that Asami is in every way a product of that inequality, abuse, and extortion, and symbolically a manifestation of that cultural anxiety: Asami is the woman every man fears. In some ways everything Aoyama is put through is a kind of retribution for his attempt to forget or ignore his wife after death.

In the end analysis it is a well shot film, decently written script, interesting premise, and terrifyingly well executed horror and psychological thriller. There are a few parts early on and during the investigation of Asami’s background that do feel as though they drag on a little, but ultimately to little real distraction. My advice going into this film is as follows:

1) Don’t expect a constant fright-fest/roller-coaster of screams/scare-o-rama sort of film. You’ll be made slightly uncomfortable at best throughout most of the film, until it all culminates in the king of uncomfortable moments near the end, but you won’t be jumping out of your seat.

2) Know that the romance is there, but do not look at it as some kind of cutesy or mushy romance. If anything, go out of your way to pick out how many ways the relationship is awkward or creepy. Keep in mind that he’s not trying to recreate his wife in her prime, but during her illness when he neglected her the most. It may actually help you sit through the early segment of the film if you’re not a fan of the romance subplot.

3) Pay attention. It’s really not a “sit on your laptop and browse the internet while playing your DS with the movie in the background” kind of film, don’t bother trying. The script does a good job of being subtle: it all carries on like normal banter, but there is meaning behind every line, and you’re liable to miss all of it if your attention is divided. That’s it really, anything else I could mention I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt with and assume you can work the little details out on your own. With that I’ll leave you to go find yourself a copy of Audition and enjoy it on your own! Join me here again tomorrow night for a Mischief Night special, and then one last horror review on Halloween day!

iStalk? uStalk!