The Ghibli Quest Continues with The Owl in the Rafters

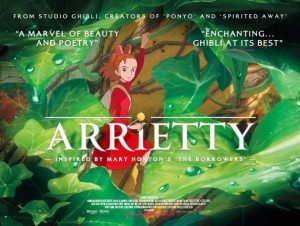

Welcome back to the Owl in the Rafters! Today I’d like to talk about a lesser known side of one of the biggest names in anime: Studio Ghibli. American fans are probably already aware, but the US theater release of The Secret World of Arrietty was this past February 17th, and despite lagging behind the original Japanese release by two years (and the UK release by about seven months) the wait proved well worth it.

As per the usual, Ghibli’s art team makes a beautiful showing of the film, the animation is clean and dynamic, the designs charming and modest, and Disney’s choice of seasoned high profile actors mixed with bits of their fresh crop of child talent was a refreshing change of pace and improvement from the US anime industry’s usual slim pickings of stock voices. Amidst the forest of familiar names crowding the opening credits however is one name most anime fans and film goers alike ought to find very much unfamiliar: Hiromasa Yonebayashi.

This newcomer was given Hayao Miyazaki’s usual role of director while Miyazaki played co-pilot to screenplay staff. Yonebayashi’s name should be new to you for good reason, he’s never directed a thing in his life before Arrietty. He has done key animation, inbetween animation, and clean-up art on a wide variety of Ghibli films since 1997 along with a handful of other non Ghibli properties. (Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade being one of the better known.) Not counting Goro Miyazaki as truly “new blood” to the company, The Secret World of Arrietty thus marks the first film to be taken out of the hands of founding members Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata’s since 2002 when Hiroyuki Morita directed The Cat Returns.

Taking a step back in Ghibli’s history of directors: in 1995 Miyazaki and Takahata allowed a man named Yoshifumi Kondou to direct a Ghibli film called Whisper of the Heart which was met with overwhelming success. Not only did the film win a number of awards, it also made top grossing domestic film of that year. It was this great success that lead to the film The Cat Returns which follows the Baron character from Whisper of the Heart on his own adventures. It is unfortunate but the director of Whisper of the Heart, Yoshifumi Kondou, whom Miyazaki and Takahata had both expected to be their protegee in Ghibli once they retired, died in 1998 at 47 years old.

Ghibli’s only other major attempt at letting a younger staff member take control of a project had been in 1993, when Tomomi Mochizuki was asked to direct the made for TV movie, Ocean Waves. Much to the company’s disappointment, the small project was not only pushed over budget but past deadlines as well. While not a total flop, the film was still a notable failure in Ghibli’s search for reliable new directors.

Other than Kondou, Morita, and the recent Yonebayashi, Goro Miyazaki, Hayao Miyazaki’s own son, is the only other director apart from the founding duo to have directed any major Ghibli films. Of those three name, Goro is also the only one to have returned to the director’s seat again. But as you may know, his 2006 film Tales from Earthsea and the more recent From Up on Poppy Hill were both met with resounding disappointment.  Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea books have long been a personal favorite of Hayao Miyazaki’s and a film project he had long looked forward to doing himself. When Toshio Suzuki, producer of the film and current CEO of studio Ghibli, first approached Goro Miyazaki in hopes of encouraging him to pick up directing, it was in the hope that Goro could rise to fill the role of protegee that the company had long been searching for. It was also allegedly Suzuki’s idea for Goro’s debut film to be the one project his father never saw through to the end. Ideally Goro’s success with Tales From Earthsea should have been an auspicious way to launch his career, but the film was berated as having a poor mix of original content and references to source material.

Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea books have long been a personal favorite of Hayao Miyazaki’s and a film project he had long looked forward to doing himself. When Toshio Suzuki, producer of the film and current CEO of studio Ghibli, first approached Goro Miyazaki in hopes of encouraging him to pick up directing, it was in the hope that Goro could rise to fill the role of protegee that the company had long been searching for. It was also allegedly Suzuki’s idea for Goro’s debut film to be the one project his father never saw through to the end. Ideally Goro’s success with Tales From Earthsea should have been an auspicious way to launch his career, but the film was berated as having a poor mix of original content and references to source material.

His most recent film, From Up on Poppy Hill which was released in the summer of 2011, was considered less of a blunder than Tales From Earthsea, but still fell prey to criticism of Goro’s directing talents. Praised as a beautifully illustrated film with a cute and simple story, but ultimately bland and predictable plot and uninspired film direction.

If it hasn’t become apparent by now the point I’m getting at here is that Ghibli must now face the fact that both its head directors are approaching their twilight years (Hayao Miyazaki is currently 71 and Isao Takahata is 76) and the company has thus far no successors in place to really lead the studio once they step down. The question I’d like to address is whether or not The Secret World of Arrietty had what it takes to put Hiromasa Yonebayashi in line to inherit the throne of Ghibli’s chief director.

In truth it is a remarkably hard call to make. The film did a number of things both very well and very poorly. The best parts were Yonebayashi’s absolutely breathtaking approach to Ghibli’s staple scenery work, while the story, characters, and pacing each managed to fall a little flat. At the bottom line however, the film was a marvelous fusion of Ghibli’s usual sprawling, awe inspiring, fantasy world coupled with the homely and familiar charm of Ghibli’s iconic My Neighbor Totoro that succeeded in all the categories Ghibli is best known for. The bottom line is that for all the little things I can pick at individually, I can’t honestly say I ever ever actually bored or unsatisfied with the film.

Fellow content provider, MollyBibbles, has already done an article on the film itself, so I won’t blather at you about my own assessment or any nitty gritty details. What I will blather at you about is my interpretation of Miyazaki’s criteria for an adequate successor. Once I’m through with some background on Ghibli’s history, I’ll leave it to you to watch The Secret World of Arrietty on your own, either again or for the first time, and decide for yourself whether or not Yonebayashi’s direction fits the pattern of Ghibli’s history.

I assume many of you, if not most of you, are familiar with Studio Ghibli and their bigger titles,  like My Neighbor Totoro, Nausica of the Valley of the Wind, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, and more recently Ponyo. Even if you aren’t, most of it is easy enough to find online with some fairly basic use of common search engines. What might be a little more interesting to hear about is Miyazaki’s career before Ghibli, and by no coincidence Isao Takahata’s career as well. Both founding and pillar members of Ghibli worked together for a company once known as Calpis Comic Theater. The company would later go through various subtle name changes based upon the company shuffling between different sponsors and eventually become World Masterpiece Theater, the title by which the company is best known by now.

like My Neighbor Totoro, Nausica of the Valley of the Wind, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, and more recently Ponyo. Even if you aren’t, most of it is easy enough to find online with some fairly basic use of common search engines. What might be a little more interesting to hear about is Miyazaki’s career before Ghibli, and by no coincidence Isao Takahata’s career as well. Both founding and pillar members of Ghibli worked together for a company once known as Calpis Comic Theater. The company would later go through various subtle name changes based upon the company shuffling between different sponsors and eventually become World Masterpiece Theater, the title by which the company is best known by now.

The name may not seem so at first glance but it is quite literal: the project’s entire line up of annual TV series was comprised of anime adaptations of world famous Western literature. Some of the project’s more recognizable titles (to a young modern American audience anyway) include adaptations of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Johann Wyss’ The Swiss Family Robbinson, Louisa Alcott’s Little Women, J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and Maria von Trapp’s The Story of the Trapp Family Singers, and even an original interpretation of Eric Knight’s Lassie Come Home. While working for World Masterpiece Theater between 1969 and 1979, Miyazaki did animation work in six different television series, all based upon different Western novels and book series, while Takahata was already a well established director at the time and was called upon to direct five different World Masterpiece Theater series, four of which included Miyazaki on staff.

The first of these four proto-Ghibli titles was the 1974 series, Heidi Girl of the Alps, based off of the Johanna Spyri novel Heidi in which Isao Takahata was both chief director as well as storyboard artist on several early episodes and Miyazaki actually did not do any real paint to celluloid animating, but worked on animation layout (actually arranging cels on the camera and in doing so determining the perceived camera angles, and camera movement in the finished product) as well as continuity checking (ensuring the story’s fluid structure as supported/conveyed through the visuals) and strangely enough he is credited as having had a hand in writing the opening theme’s lyrics.

The first of these four proto-Ghibli titles was the 1974 series, Heidi Girl of the Alps, based off of the Johanna Spyri novel Heidi in which Isao Takahata was both chief director as well as storyboard artist on several early episodes and Miyazaki actually did not do any real paint to celluloid animating, but worked on animation layout (actually arranging cels on the camera and in doing so determining the perceived camera angles, and camera movement in the finished product) as well as continuity checking (ensuring the story’s fluid structure as supported/conveyed through the visuals) and strangely enough he is credited as having had a hand in writing the opening theme’s lyrics.

If you are somehow unfamiliar with the title, the original novel, written in the late 1800s by the aforementioned Johanna Spyri, is quite easily the best known work of Swiss literature on a global scale. The book has had over a dozen different film and television adaptations as well as two unofficial sequels, and even has an entire collection of districts named Heidiland after the novel and protagonist, located just south of the Principality of Liechtenstein. Heidiland’s economy also constitutes a large bulk of Switzerland’s tourist traffic.

If you are somehow unfamiliar with the title, the original novel, written in the late 1800s by the aforementioned Johanna Spyri, is quite easily the best known work of Swiss literature on a global scale. The book has had over a dozen different film and television adaptations as well as two unofficial sequels, and even has an entire collection of districts named Heidiland after the novel and protagonist, located just south of the Principality of Liechtenstein. Heidiland’s economy also constitutes a large bulk of Switzerland’s tourist traffic.

Just saying it now, but I will not be detailing the plot of any of the following titles, as to prevent this from turning into an article on classic literature rather than anime.

The second title bringing Miyazaki and Takahata’s love of Western literature together was the A Dog of Flanders, based on Maria Louise Ramé’s 1872 novel of the same name and published under her pseudonym, Ouida. Like Heidi the original novel is one that has always been fairly popular in Japan for some reason and may in fact be better recognized as a classic in Japan than in some English speaking countries, even going so far as to produce a documentary in 2007, Patrasche, a Dog of Flanders – Made in Japan , exploring the history of the story and contrasting its popularity in Japan against that of it in England and Europe.

based on Maria Louise Ramé’s 1872 novel of the same name and published under her pseudonym, Ouida. Like Heidi the original novel is one that has always been fairly popular in Japan for some reason and may in fact be better recognized as a classic in Japan than in some English speaking countries, even going so far as to produce a documentary in 2007, Patrasche, a Dog of Flanders – Made in Japan , exploring the history of the story and contrasting its popularity in Japan against that of it in England and Europe.

Like Heidi, A Dog of Flanders is cemented as a classic of world literature by close to a dozen different film and television adaptations, including four different Japanese adaptations (2 animated TV series, 1 animated film, and a live-action film) of which the World Masterpiece Theater series is the first. The theme song, Yoake-no Michi, is still a well recognized as a kind of 70s television icon. The 1997 film was in fact a remake of the original 1975 TV series, and was directed by Yoshio Kuroda again, but without the involvement of either Takahata or Miyazaki. The original World Masterpiece Theater portrayal of the dog, Patrache, as a somewhat stocky cream colored dog with a kind of chestnet colored mask pattern is still a well recognized children’s entertainment icon to this day.

Like Heidi, A Dog of Flanders is cemented as a classic of world literature by close to a dozen different film and television adaptations, including four different Japanese adaptations (2 animated TV series, 1 animated film, and a live-action film) of which the World Masterpiece Theater series is the first. The theme song, Yoake-no Michi, is still a well recognized as a kind of 70s television icon. The 1997 film was in fact a remake of the original 1975 TV series, and was directed by Yoshio Kuroda again, but without the involvement of either Takahata or Miyazaki. The original World Masterpiece Theater portrayal of the dog, Patrache, as a somewhat stocky cream colored dog with a kind of chestnet colored mask pattern is still a well recognized children’s entertainment icon to this day.

Next on the list is From Apennines to the Andes, aka 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother another TV series directed by Isao Takahata with Miyazaki reprising his roles with continuity and layout. The source material on this one is actuality the novel Cuore (lit.”Heart”), by Edmondo De Amicis. The original title From Apennines to the Andes is derived from a single chapter within the original novel, “Dagli Appennini alle Ande”, which as you may have guessed translates literally as “From Apennines to the Andes.”

Next on the list is From Apennines to the Andes, aka 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother another TV series directed by Isao Takahata with Miyazaki reprising his roles with continuity and layout. The source material on this one is actuality the novel Cuore (lit.”Heart”), by Edmondo De Amicis. The original title From Apennines to the Andes is derived from a single chapter within the original novel, “Dagli Appennini alle Ande”, which as you may have guessed translates literally as “From Apennines to the Andes.”

The original 1886 Italian children’s novel was largely successful for its poignant and relatively evenhanded approach at commentary on the state of Italian society during the Italian Unification. As such it has proven hugely popular in countries undergoing civil unrest, including 1950s Israel, 1960s-70s Mexico and Latin America, and Communist China from where it spread across most of mainland Asia and naturally, to Japan.

The original 1886 Italian children’s novel was largely successful for its poignant and relatively evenhanded approach at commentary on the state of Italian society during the Italian Unification. As such it has proven hugely popular in countries undergoing civil unrest, including 1950s Israel, 1960s-70s Mexico and Latin America, and Communist China from where it spread across most of mainland Asia and naturally, to Japan.

This particular story has seen less adaptations than the others, with just one live-action adaptation in its homeland of Italy, and the Japanese animated television series I just mentioned, followed by an anime movie in 1980 which was then remade in 1999. There was a second TV anime series run in 1981 under the name Ai no Gakkou: Cuore Monogatari lit. “School of Love: The Story of Cuore,” derived from the Chinese translation of the novel’s title as “Education of Love.”

Finally, both Takahata and Miyazaki worked on the 1979 TV series, Akage no Anne (lit. “Red Hair Anne”) based on Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.  Where as Takahata’s take on Heidi and Cuore had been more liberal and tweaked where appropriate for his intended Japanese audience, he chose to keep Akage no Anne much closer to the original novel. The original Anne of Green Gables is another book that had seen over a dozen theater films, made for TV movies, TV series, and even live stage adaptations. Also rounding out the line up of international success, Lucy Maud Montgomery presents a Canadian classic to the list of source material.

Where as Takahata’s take on Heidi and Cuore had been more liberal and tweaked where appropriate for his intended Japanese audience, he chose to keep Akage no Anne much closer to the original novel. The original Anne of Green Gables is another book that had seen over a dozen theater films, made for TV movies, TV series, and even live stage adaptations. Also rounding out the line up of international success, Lucy Maud Montgomery presents a Canadian classic to the list of source material.

So, how does this all came to bare on Yonebayashi’s performance in directing The Secret World of Arrietty? His interpretation of the original source material may have been very liberal but it was not actually the real source of the film’s shortcoming. The plot was simple but effective, and the actual story had only minor snags, but as an overall film experience the art and audio direction compensated thoroughly.

So, how does this all came to bare on Yonebayashi’s performance in directing The Secret World of Arrietty? His interpretation of the original source material may have been very liberal but it was not actually the real source of the film’s shortcoming. The plot was simple but effective, and the actual story had only minor snags, but as an overall film experience the art and audio direction compensated thoroughly.

Ghibli has always been more about making entertaining children’s films first and foremost, with the art taking top priority to that end: in this Yonebayashi succeeded. Looking back at Miyazaki and Takahata’s history, neither have had any serious qualms with tampering with integrity to source material, so Yonebayashi’s fiddling with Mary Norton’s The Borrowers should really come as no surprise. Miyazaki and Takahata also both have a history of taking true classics of children’s literature and breathing a little life back into them for a new generation without creating films that erase the need or want to read the original novels: In this too, Yonebayashi succeeded. Keeping in mind Ghibli’s history of new directors as well as the history of their two big directors, I ask that you keep your eyes and ears open in the coming years, because while more new directors are sure to crop up, I’m willing to bet that Hiromasa Yonebayashi is a name we that haven’t heard the last of.

I don’t really care if I’m shot down for saying it, but I thought Tales Of Earthsea was a mess. I was falling asleep and shaking my head at the same time.

I’m kinda sad to hear critics aren’t enjoying Poppy Hill since I was told it has a more grounded love story by Akihiko Yamashita. I still look forward to it, but at the same time I’m not suddenly worried considering how much I really disliked Earthsea.

You’re not alone. I managed to enjoy Earthsea for the art, but the story really was just a mess. Poppy Hill sounds like it is at least more watchable, but now the complaint is that it just wasn’t anything special. I do feel like it is a tad unfair however. If he wasn’t Hayao’s son I feel like he might have been given a better reception as a director over all. As it stands it feels like people are just waiting for him to fail, rather than eager to see how he can grow and develop

Well, I mean if there was anything I’d say about Earthsea is I felt the character progression and developing was lacking. It somehow proved to be more subtle than a Ghibli work usually is, and as such you end up with literally characters you can’t grasp. I can’t picture a single character from that movie besides the villain and only because he looked creepy, not because he was actually threatening.