Kabuki 101 With Kent Williams – Anime World Chicago 2011

Here we are, the advent of the new school year for us Americans. The con season is slowing down and the sugar rush is beginning to fade. Back to your seats, class, because you’re about to get schooled by master puppeteer and Kabuki-Sensei, Kent Williams.

Anime World Chicago has come to a happy close and the I finally managed to catch up on much needed sleep. Now that I’m fresh and lively, let’s get down to business! For the next while and a half I am going to give you an insiders look into possibly the most amusing panel AWC had to offer: Kent Williams’ beginner’s guide to Kabuki. Before we dive head first into the nonsense, let’s look into an incredibly brief history of Kabuki.

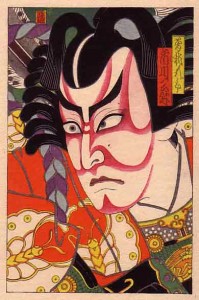

Kabuki, a 400-year-old jewel of Japanese culture, is the art of infusing story-telling, theater and traditional dancing. Originally danced by women taking on both female and male roles, the form became instantly popular during the Shogun era of the 1600’s. Popularized by Izumo no Okuni’s Kyoto performances in dry river beds, the art quickly gained steam when rivaling troops began developing Kabuki as an ensemble form instead of a solo practice.

Kent Williams used an image accessible to western audiences by comparing the dramatic practice of Kabuki to that of a European equivalent, Shakespearean drama. Like Shakespeare, Kabuki has its archetypal roles, the strong, proud Samurai, the soft, gentle women and the mythical demon. Stop and ponder a moment. This set up is very similar to that of many European fairy tales turned Disney movies which utilize the over used trope of handsome, strong and loyal prince saves/protects/proves his manliness to the weak willed princess by defeating the ugly/evil/dragon-like “demon”. Stories may vary from play to play, such as major historical events, domestic plays or love-suicides and dance pieces, but the stereotypes remain unchanged within Kabuki’s expansive heritage.

The Physicality

Mr. Williams began his panel by giving us and his willing volunteers a crash-course in Kabuki history and movement. Akin to a ballet, Kabuki utilizes a sort of movement-based language to portray certain emotions and actions without spoken word. This allows the audience to understand the story and intention of the characters without the aid of a script. Having a keen eye for theatrical nuance is useful but mostly unnecessary. The basic human emotions get a bit of the cartoon treatment, making it simple for us to process. Happiness shows laughing eyes peeking above the fan while laughter adds just a bit of a shoulder bounce. Sadness may be less jovial, more sunken and droopy in carriage. See? Simple as that.

The men, or strong, manly Samurai, portray more of a masculine image and rarely break their cold appearance. Unlike the women, they are unwavering in reserve. Their stance is grounded and large with their feet spread beyond hip distance, toes pointed dead ahead and a slight bend in the knees. This position exudes strength, fortitude and bravery, all characteristics of the Kabuki Samurai. Women, however, whose stance remains narrow with a slight pigeon toe and knock knees, stay dainty, soft and modest. You don’t see “Joan of Arch” women here. Traditional stereotypes stay very much intact to this day in Kabuki Theater.

The actors in a Kabuki play must have an extreme sense of balance, coordination and grace, again, like that of a ballerina. They must give off the illusion of merely gliding across the stage by doing something like a forward moonwalk where the feet closely cut in front of the other with no change in body level. Imagine trying to walk down the street without bobbing. Your movements are now a bit more restrained. With a perfectly straight back, you gives us the image of confidence as you glide effortlessly across the floor. To get a better idea of what we’re getting at here, I dare you to forward moonwalk from one end of your room to the next with a book on the top of your head and tell me how it goes.

The Costume

Why Mr. Williams would trust a room of anime fans with his antique Kimonos is beyond me, but it sure completed the image and gave the volunteers a fuller understanding of the art. This technique is great for tactile learners like myself. Complete with an arsenal of traditional kimono’s, painted fans and face paint, these lucky participants who just happened to stumble into the panel that Saturday morning got the whole package. With that said, why don’t we look into the panel itself?

For ten unnerving minutes, Bismarck and I sat off centered with bated breath as we watched a hand full of wary attendees fumble with their dress. Confusion and vacancy spread across their faces as they attempted to wrap their Kimonos like a bath robe. Kesho, traditional Kabuki makeup, was applied to the willing to go the extra mile and pesky western shoes were kicked off despite the occasional displeased mumble. Mr. Williams’ Kabuki production was underway.

Excuse this quick detour as I regale for you the true meaning of the makeup as I see this fit. Think back to the roles and stereotypical characteristics of Kabuki’s roles. The face is enhanced and accentuated in ways that are now iconic identifiers of Kabuki to western audiences. The stark lines around the lips and eye brows give greater attention to the facial features. Atop the white base, this creates an almost animalistic or supernatural appearance. The colors are significant in that they identify the person’s role in the story. Red paint signifies strength and heroism like that of the Samurai role. Blue or black stands for villainy or evil associated with the demon or “big baddy”. In the language of color, your choice of pigment can the window into your true character.

Tangent aside, let us continue on with the panel as there is still much to cover! Suited up and ready for Kabuki action, our wary volunteers gripped their fans in readiness. Their lightening fast training was set to begin.

The Story

Kabuki, again, similar to ballet or Shakespeare, works from a repertoire of well established plays. Kabuki productions are usually full-day works as a means of escaping from everyday life. (If you’ve ever wondered why Bollywood films are so dang long, the same principal applies. Just a thought random though for you.) Today, we’ll be focusing on a rather short one act play, Issunboshi.

Here’s where the fun began. Mr. Williams, with enthusiasm and ten minutes to spare, set the story of Issunboshi upon our players. A child’s fairy tale, Issunboshi (trans. One-Inch Boy) tells of a one-inch-tall boy, who likens himself a Samurai, born unto an old couple. Realizing that he will never grow, Issunboshi leaves him home to find his place in the world. The boy, given a sewing needle for a sword by his mother, travels to the city to find work and happens upon a house of great wealth, staying with its inhabitants for ten years. Issunboshi, while traveling with the house’s beautiful daughter, is eaten whole by a demon, an Oni. Remembering that he still has his sewing needle, Issunboshi prods at the demon from inside his stomach. The demon spits him out and runs away, dropping a magical mallet. The daughter then uses the magic of the mallet to make Issunboshi grow to full height and they all live happily ever after… Who doesn’t love story time?

Of course, given the time constraints and the number of volunteers, Mr. Williams had to make some edits to the story making for some chuckles and good times. I hope you enjoyed this brief look into Kent William’s world of Kabuki. I’ll be back in the coming weeks with a wrap up of Anime World Chicago 2011 and some fresh-baked animu reviews, just as you like them. Now, suit up and conquer the stage with your new-found powers of Kabuki!

And a huge, theatrical thank you to Kent Williams and his wonderfully willing volunteers for your ability to explore new grounds and to allow me to share your hilarious adventures with the world. See you at Anime World Chicago 2012!

[…] year fellow content provider, Molly Rants-a-Lot, did a write up on Kent Williams’ Kabuki workshop panel at the first AWC, which has remained more or less unchanged. This year’s crash course was […]