Howling At The Moon With Takahashi Yoshihiro And The Owl In The Rafters

Welcome back to another week in The Rafters! Normally I try to give you the bird’s eye view on the overarching careers of various artists, authors, and directors, but this week I’m taking things easy and highlighting just a small portion of one artist’s long list of works. That artist is Takahashi Yoshihiro. Some of his popular works include such titles as White Soldier Yamato, Armor of the Soldier Gamu, Fang of the White Lotus, Boy and Dog, FANG, Lassie, and many many more. But while Takahashi has published a long list of manga starting as far back as the 1960s, his big hit series and the focal point of this review, is the long running story that began with his award winning hit title, Ginga Nagareboshi Gin.

Inspired by stories of domestic dogs in Japan turned stray learning to band together in packs as wild dogs, Takahashi began the story that would become the backbone of his career. In fact, while the titles I listed briefly above may not have let on to it, all of Takahashi’s major works have not only been about dogs, but had dogs as the main characters. This unique quirk of Takahashi’s writing style along with his distinctive art style has built a genre all his own in manga telling stories from the perspective of animals.

His career wasn’t built on just one little gimmick however; Takahashi’s grasp on the shonen demographic and all its subtle little nuances, tropes, and archetypes is unparalleled. If you take away the fuzzy tail wagging exterior and really strip his stories down to the bare bones, you’ll find that at its core, Takahashi’s manga uphold the purest embodiment of all the virtues that have been the very image of shonen since the 1960s. (I must confess however that those values have changed ever so slightly in recent years, so perhaps those old fashioned values born of the classic 60s manga aren’t as familiar anymore.)

All of this may not paint a very clear picture in your head just yet, so rather than continue blathering on about literary theory, I’ll start on the synopsis of Takahashi’s big breakthrough manga title.

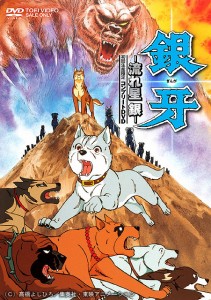

Ginga Nagareboshi Gin ran in the Weekly Shonen Jump for four years between 1983 and 1987, amassing 18 first edition volumes and a 21 episode anime series in 1986. The title translates literally as “Silver Shooting Star/Falling Star/Meteor, Gin”; Gin being the name of the main character, but also translatable as “Silver”. Silver Meteor Silver just doesn’t sound right, though.

The story starts throwing curve-balls right off the bat. In an industry dominated by giant robots, sports, and other stories centered on young heroes mirroring the intended audience, a story about dogs, while novel, does lack a certain personal connection with the consumer in a mainstream market. In light of this obvious hurdle, Takahashi avoids jumping right to the dogs and focuses at first on a young boy named Daisuke and his family instead.

Daisuke’s parents run a ski resort in Northern Japan and his grandfather, Takeda Gohei, is a grizzly looking old man and a reputable bear hunter, even in his old age. So, the story begins with the recollection of Gohei’s bitter feud with a fearsome, legendary bear living in the nearby mountains. Five years prior to the start of the story, Gohei and his faithful hunting dog, Shiro encountered the dreaded red-maned bear, Akakabuto (literally: “Red Helm”) and in a desperate struggle, Akakabuto scared Gohei across the face before Gohei managed to land a bullet clear through one of Akakabuto’s eyes as the brave bear hound, Shiro fought with the bear and ultimately fell with him to his death when they both plummeted into a frozen river.

The demon bear, Akakabuto did not die in the fall however, nor did he die from the bullet that had pierced his eye and lodged itself in his brain. Instead, the brain damage from the bullet drove the already fearsome bear to dementia. In his madness, Akakabuto found he had no need for hibernation and began rampaging through the mountains even in the dead of winter.

So, in the present, the young Daisuke watches as Gohei and two other hunters venture off into the mountains with Riki, the son of Shiro, and two other hunting dogs. Back at home, Daisuke’s dog Fuji gives birth to her first litter, and to Riki’s pups. Among this third generation of hunting dogs is a rare silver haired tora-ge, “Tiger Striped” Akita pup. This young pup, is our hero, Gin.

Meanwhile, out in the mountains int he midst of a snow storm, Gohei and his hunting party come face to face with the crazed bear, who has begun attacking the tourists on the ski slope out of hunger. Despite the brain damage, Akakabuto has not become stupid however, and his fearsome keen intellect remains fully intact if not sharpened even by the years of madness. And so Gohei’s hunting party is met with a gruesome end when only Gohei and Riki are left alive, but stranded in the mountains. Once the rest of the hunting party is found with no signs of Gohei and Riki, the towns’ folk resolve to band together a search party to track down whatever remains of the old hunter and his dog. In an act of adolescent defiance after being told to stay at home, Daisuke sneaks out on his own to track down Gohei with the little pup, Gin, tucked away into his jacket.

Daisuke does eventually stumble into Gohei and Riki out in the woods, but when he does he finds them embroiled in a fight to the death with Akakabuto. In a sudden act of foolish bravery, the newborn Gin attempts to aid his father, Riki, only to learn the true depths of fear. Riki musters up the last of his strength to rescue his son from danger however, but at the cost of his life, and so Gin watches on in despair as Akakabuto deals his father, Riki, one final blow.

So, the deep seated vendetta of his bloodline and the trauma of his father’s death fuel Gin’s search for power as he is taken from Daisuke by old Gohei to be trained as the hunting dog to succeed and surpass both his father and grandfather in the ongoing battle against Akakabuto. What ensues is perhaps one of my favorite training arcs in any manga series; where Gohei ruthlessly forces Gin through a series of ridiculous training routines. Meanwhile, Daisuke desperately tries to become a man and a hunter worthy of winning his dog back from the grip pf his grandfather’s obsessive Captain Ahab syndrome with Akakabuto.

The story gradually shifts tone however, and the dogs are given both the spotlight and their own voices once the first rival dog, John, appears in the story. There is a short series of other adventures between Daisuke, Gin, and John that eventually lead up to Gin running away from both Gohei and Daisuke to join a pack of wild dogs living out in the mountains.

Here is where things get really interesting. What started looking like it would be a generic battle manga format of repeating training and battle arcs about a boy and his dog fighting bears, suddenly shifts gears towards being a full-blown Chanbara epic. (Chanbara is a Japanese onomatopoeia for the sound of swords clashing, and the term Chanbara Film, refers to classic samurai swordplay films.)

When the wild pack element of the story is introduced the group dynamic suddenly parallels that of old samurai epics. The way each character is introduced; the way Gin wins over his allies through acts of heroism; the way the linage of dog pedigrees mirrors traditional Samurai families;  the way Akakabuto battles and subjugates other bears to defend his territory; they all perfectly replicate the frame work of the quintessential samurai epics and their stories of the lone, heroic ronin gathering renegade and mercenary samurai together to oppose a mighty corrupt shogunate in the waning years of the Sengoku period.

the way Akakabuto battles and subjugates other bears to defend his territory; they all perfectly replicate the frame work of the quintessential samurai epics and their stories of the lone, heroic ronin gathering renegade and mercenary samurai together to oppose a mighty corrupt shogunate in the waning years of the Sengoku period.

So, the samurai dog story goes on and Gin’s pack grows until they finally come to their destined battle with Akakabuto himself. In the epilogue of the story, the wild dog pack takes the mountain territory for themselves in the wake of Akakabuto’s defeat and create a safe haven for wild dogs to live. This paradise for wild dogs sets the stage for the sequel to Ginga Nagareboshi Gin, another hit manga turned anime Ginga Densetsu Weed. (lit: Silver Legend Weed)

So, after 190 pages of this first epic tale of samurai-like pack of wild dogs ended its publication in the Weekly Shonen Jump in 1987. Despite good sales of the manga, and the success of the 21 episode anime series, the manga has yet to be translated and released outside of Japan, and the anime has only ever been dubbed in Swedish and Danish. If you’re a bit confused by those choice languages, you aren’t alone. Perhaps it has to do with the familiar terrain of snowy wooded mountains, but for whatever reason, even though Ginga Nagareboshi Gin wasn’t released in English, Spanish, German, Italian, or any of the other major languages anime tends to be most popular in, it was a huge hit in Nordic countries like Finland, Denmark, and Sweden.

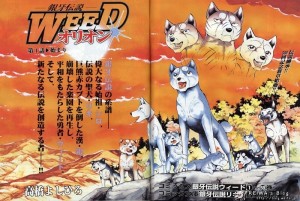

Over a decade later, after publishing more than half a dozen other small serialized titles, Takahashi returned to his faithful hero, Gin, to start what has since become his biggest series. Starting in 1999 Takahashi began publishing a sequel to Ginga Nagareboshi Gin, entitled Ginga Densetsu Weed (lit: Silver Legend Weed), in Bungeisha’s seinen magazine, the Weekly Manga Goraku. Ironically enough, despite the change of target audience, the sequel is less brutal than its predecessor, but only by comparison. It was a different issue in the early 80s, but since the 1990s the policies on censorship and audience appropriate material in anime and manga in Japan have shifted, and so the level of violence and bloodshed in Takahashi’s work now falls more safely under the seinen category.

Ginga Densetsu Weed brings our focus onto a young stray pup with no name.

He is a meager little newborn who has never known his father and must take care of his ailing mother by himself. When a messenger from the wild dogs’ safe haven finds the boy and his sickly mother, he reveals to the young pup that he is in fact the son of the great pack leader, Gin. The little pup is given the name Weed, a name appropriate for the resilient little whelp growing up in the wild.

He is a meager little newborn who has never known his father and must take care of his ailing mother by himself. When a messenger from the wild dogs’ safe haven finds the boy and his sickly mother, he reveals to the young pup that he is in fact the son of the great pack leader, Gin. The little pup is given the name Weed, a name appropriate for the resilient little whelp growing up in the wild.

Weed’s story differs slightly from Gin’s, in that where Gin was honest, valiant and brave, Weed comes across as honest but also naive, as a little less valiant and more blindly optimistic, and not so much brave as just reckless. Accompanied by his father’s old comrade Smith, the cowardly english setter, G.B. and the young golden retriever, Mel, Weed begins his journey home and learns what it means to be a fighter, a leader, and an honest person/dog. When Weed arrives at the territory his father once established for the wild dogs he is told that his father is away and in the absence of their leader, the wild dogs’ territory has been terrorized by a monstrous dog, known only as “The Beast”.

Once the Beast is dealt with, the story starts onto a plot that has often been compared to that of the popular Naruto, because of the protagonists’ shared stubbornness, naivete, and their habit of making new friends by picking fights with strangers. Weed and his father’s pack learn that Gin has been injured and taken hostage by a sinister wild dog with his own pack of followers called Hougen. Intent on rescuing his father, Weed begins a long journey across Japan in search of wild dogs who will help join his father’s pack to bring down Hougen. Some of the dogs he meets are friends of his father, while others are infamous pack leaders themselves, and other still are just lone strays. One way or another, Weed fights his way into the hearts of his allies and wins over a small army of his own to face down Hougen and his generals.

As I said before, this series really does make a very clever point of highlighting some classical Japanese tropes and archetypes as Weed roams around a Bakumatsu-like world of wild dogs living in the mountains of northern Japan. If I said that Gin’s story reenacted s snapshot of the Sengoku period through hunting dogs and bears, then Weed’s story mirrors the brief interim of time between early western contact with Japan and the Bakumatsu revolution.

Like it’s predecessor however, Ginga Densetsu Weed never saw much attention outside of Japan. There was a Danish dub of the 26 episode anime released in 2005, and the manga was licensed in Taiwan while the manga saw a limited North American release in English by ComicsOne, touching on only a small fraction of the 60 volume long series –that includes all of Ginga Densetsu Weed‘s main story and in addition a number of shorts, including a prequel detailing the life of Gin’s father/Weed’s Grandfather, Riki, and a short sequel story of Weed’s son, Orion.

Although Gin and Weed are the only two of Takahashi’s titles that you’re likely to find in any sort of English format, but even so, I want to encourage you to look into Takahashi’s work in whatever forms you can find it. He has been a consistently impressive author, with his nostalgic art and writing styles, and one of only a small handful of veteran authors/artists left from the first generation of creators behind Shueisha’s Weekly Shonen Jump still in publication. So for now, I hope you’ve found something interesting in this tiny snippet of Takahashi Yoshihiro’s career. This has been the Owl in the Rafters, over and out!

Guys I have a confession……. I let the dogs out >.<

Ginga Nagareboshi Gin > is a great series we are watching in anime club.

I admit the animation quality on the anime series aren’t stellar, mostly because animal anatomy isn’t exactly a common focus for shounen anime, so there are some quirks in the animation from time to time, but despite that they’re both really fun to watch. The manga are still my top choice though, and they really are fantastic.

[…] of other shows, including Full Moon o Sagashite, Hell Girl, Solty Rei, Zipang, Ginga Densetsu Weed, which I have reviewed before, and various episodes of other shows. Oddly his only other directorial role happens to have been on […]